Rivera’s New York Winter Returns

12-08-2011

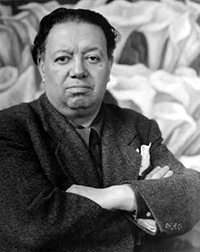

Eighty years ago this month, the fledgling Museum of Modern Art opened a solo show devoted to Diego Rivera [right], described in the New York Sun as “the most talked about artist on this side of the Atlantic.” To commemorate that occasion, MoMA has reassembled a selection of the frescoes he painted for the exhibition, together with supporting material. Although it’s far from complete—only five of the eight so-called portable murals are on view—the current show (through May 14) and its excellent catalogue make it clear why Rivera and his art were so notorious, as well as illustrating his relevance today.

Celebrated for acres of murals in his native Mexico, Rivera was a supersize personality with a talent for self-promotion that rivaled his artistic gifts. By the time he arrived in Gotham in November 1931 to prepare for his MoMA exhibition, he had generated more ink than a giant squid. His recent expulsion from the Communist Party (he took money from capitalist patrons, and even worse, dared to criticize Stalin) made him a cause célèbre on the left, and his announcement that he would paint fresco panels at the museum sparked the general public’s interest. They had read about his marvelous murals in Mexico City, Cuernavaca and San Francisco, where people could watch him at work on the scaffold like an American incarnation of Michelangelo, and wanted to see the performance for themselves.

For its part, MoMA was looking for a crowd-pleaser. Opened only two weeks after the 1929 stock market crash, and already viewed as a plaything of those we now call the 1%, the museum was still struggling to find its audience. Rivera’s international renown and devotion to “art for the masses,” plus the popularity of Mexican folk art and crafts, helped redirect traffic that normally bypassed the museum’s first home in the Heckscher Building.

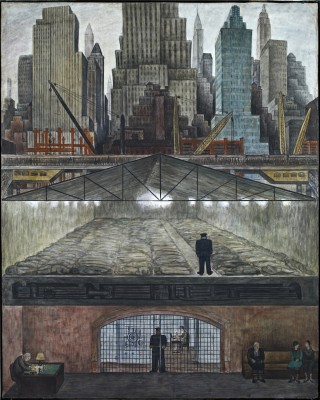

Notwithstanding the disappointment that Rivera painted his frescoes in a makeshift studio that was closed to the public, the show was a hit. He completed five panels in time for the December 23rd opening, and finished three more during the exhibition’s run. Four of them are details of his Mexican murals, and one is an original composition dealing with the repression of workers during the recent Mexican revolution. The last three were inspired by his impressions of New York City, where, in spite of the worsening economy, a building boom was in progress. The Empire State, Irving Trust, McGraw-Hill and  Chrysler Buildings were brand new, and Rockefeller Center was under construction. These and other American Century landmarks found their way into “Frozen Assets” [right], the most famous of his MoMA frescoes. (Since the Rockefellers, major MoMA patrons, were paying Rivera’s bills, it’s hardly surprising that Rock Center is prominently featured.) The painting now belongs to the museum in the former home of one of his Mexican mistresses, Dolores Olmedo, but for this occasion it has returned to the city of its birth.

Chrysler Buildings were brand new, and Rockefeller Center was under construction. These and other American Century landmarks found their way into “Frozen Assets” [right], the most famous of his MoMA frescoes. (Since the Rockefellers, major MoMA patrons, were paying Rivera’s bills, it’s hardly surprising that Rock Center is prominently featured.) The painting now belongs to the museum in the former home of one of his Mexican mistresses, Dolores Olmedo, but for this occasion it has returned to the city of its birth.

It’s a timely visit, to be sure. The three-tiered composition—monolithic skyscrapers looming over a human warehouse of homeless people laid out like corpses on a municipal pier, below which a wealthy few visit their heavily guarded safe deposit boxes—could be, as they say, ripped from today’s headlines. Compared to Rivera’s colorful slices of Mexican life, filled with vivid personalities and drama, this fresco is dull and static, but that’s in keeping with the elaborate visual metaphor. Construction cranes abound, straphangers crowd the el, but the city is strangely paralyzed. Even the plutocrat—who, patronage be damned, looks a lot like a Rockefeller—waiting to count his stash seems to be in a trance. It’s as if everyone is waiting for the other shoe to drop, which it did the following July, when the stock market hit bottom.

Whether Rivera actually said “I paint what I see,” a quote famously ascribed to him by E.B. White, from today’s perspective his vision of “Frozen Assets” was 20-20. In the winter of 1931-32, the economic temperature was low and falling. Eight decades on, we’re in the grip of another cold spell.

Jackson in Japan

11-10-2011

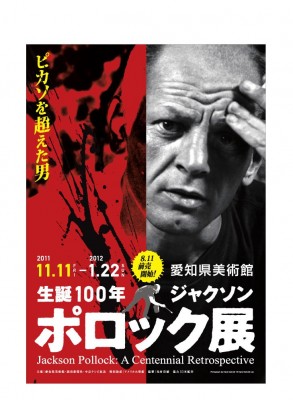

Today I find myself in the port city of Nagoya, Japan, capital of Aichi Prefecture. Seaweed for breakfast, smart toilets—I’m definitely not in Sag Harbor anymore. Fascinating as it may be, Nagoya isn’t one of the country`s top tourist destinations. Japan’s third largest city, it was heavily bombed during World War II and built back up along strictly practical lines, without much of an eye to architectural distinction. People who aren’t headed here on business usually pass through on the way from Tokyo to Kyoto. But from now until January 22, Nagoya will be a premier attraction for modern art enthusiasts from around the world. They’ll be headed to the Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art to see “Jackson Pollock: A Centennial Retrospective,” the largest exhibition of his work ever mounted in Asia.

The occasion is the one hundredth anniversary of Pollock’s birth, which actually falls on January 28, 2012, but Nagoya has kicked off the celebrations a bit early. For the actual birth year, the show will travel to Tokyo. Organized by Aichi Museum curator Tetsuya Oshima, it includes over 60 paintings and works on paper, as well as Pollock’s only mosaic, personal memorabilia, and a full-scale replica of his Springs studio (which will not travel to Tokyo), complete with a photographic reproduction of his paint-spattered floor.

The occasion is the one hundredth anniversary of Pollock’s birth, which actually falls on January 28, 2012, but Nagoya has kicked off the celebrations a bit early. For the actual birth year, the show will travel to Tokyo. Organized by Aichi Museum curator Tetsuya Oshima, it includes over 60 paintings and works on paper, as well as Pollock’s only mosaic, personal memorabilia, and a full-scale replica of his Springs studio (which will not travel to Tokyo), complete with a photographic reproduction of his paint-spattered floor.

I’m here because the Pollock-Krasner House is lending the only Pollock painting we own, an early work that shows the influence of Native American art, the Mexican muralist Jose Clemente Orozco, and Picasso. We’re also lending artifacts from the studio—paint cans, strips of colored glass left over from the mosaic, the human skull he reportedly stole from the Art Students League prop cabinet—and the Hans Namuth films of him at work. The idea is to amplify the art by pairing it with evidence of the creative process. In New York, the Springs studio and the paintings in MoMA and the Met that were made there are a hundred miles apart, but here in Nagoya they’re in adjoining rooms.

Tetsuya, who got his doctorate from the CUNY Graduate Center with a dissertation on Pollock, has scored major loans from those and other US collections, from several other countries, including Australia, Switzerland, Germany and England, and from collections here in Japan. Star of the show is one of Pollock’s two mural commissions, a masterpiece painted in 1950 for a house designed by Marcel Breuer in Lawrence, Long Island, and now in the collection of the Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art. Acquired in the 1970s under the Shah’s regime, the 6 by 8 foot canvas hasn’t been seen outside Iran since the revolution. Getting it here was a real curatorial and diplomatic coup. Needless to say, it won’t be coming to the US any time soon, so if you want to see it you’d better book your flight to Japan.

In fact no American museum will be mounting such a wide-ranging survey in honor of Pollock’s centenary. (Our own show, opening next August, will focus on his kinship with Orozco.) But considering the high regard in which Pollock is held in Japan and his influence on the development of modern art here, you could hardly ask for a more appropriate place to hold his 100th birthday party.

East End Abstractionists Take New York

10-13-2011

Just a few blocks from each other in midtown Manhattan, two galleries are currently showcasing abstract paintings and sculpture by members of the eastern Long Island artists’ community. At 724 Fifth Avenue, David Findlay Jr. Gallery’s new location, “East End: Artists of the Hamptons” focuses on nine of them, while Spanierman Gallery, at 45 East 58th Street, is showing eleven painters, several with local addresses, under the rubric “Abstract Expressionism and Its Legacy.”

Among them are Mary Abbott, Herman Cherry, Perle Fine, Gertrude Greene, Ibram Lassaw, John Little, Kyle Morris, John Opper, Alfonso Ossorio, Charlotte Park, Betty Parsons, Philip Pavia, Robert Richenburg and David Slivka. One, the painter John Ferren, is in both shows. Sadly, most are now permanent residents of Springs—in Green River Cemetery.

As I noted in my essay for the Findlay catalogue, by the 1960s the East End art colony included a sizable number of the postwar New York vanguard. They came for a respite from the pace and pressure of city life, and also to enjoy one another’s companionship in cordial surroundings. But not all the contentious energy that fueled the heated debates at The Club and the Cedar Bar was left behind in Greenwich Village. It animated the summer softball games that began as early as 1948, with two renowned scrappers, Pavia and Cherry, as regular players. Those who didn’t care for sports might be found at the beach, where hot tempers could be cooled by a dip in the ocean. In the evening there were house parties and cookouts, and perhaps an exhibition opening at Guild Hall. This sense of community was far more attractive than the scenery.

If the surroundings had an impact on the abstract expressionists, it was oblique. A color or shape glimpsed in the landscape, the quality of morning or evening light, the atmosphere of a certain moment might all play a part, but the outcome of those experiences would be subjectively interpreted rather than literally recorded. The unifying creative principle was a devotion to responsive expression. Pavia spoke for them all when he championed “the artist’s own personal experience as the basis for communication and definition.”

Many of the works in these exhibitions reflect such a process of assimilation. Fine—whose 1949 canvas, The Forest, is on view at Spanierman—once told me that her spare linear imagery was indirectly influenced by the winter landscape, in which the dark verticals of tree trunks are foiled against the snow’s whiteness. Parsons’ ambiguously titled Blue Field, also at Spanierman,could refer to a farm field like the ones near her Southold home, or to the background that supports her abstract motifs. In the Findlay show, the gnarled forms in Slivka’s energetic ink drawings have their counterparts in chunks of driftwood, and in tree roots exposed by erosion on the coastal bluffs. Similarly, Pavia’s late 1940s bronzes suggest fragments of structures weathered by wind, sand and sea. The celestial allusions in Lassaw’s open-space sculptures—like Callisto [right], named for one of Jupiter’s moons—became more frequent after he began summering in Springs, where the night sky was not obscured by the city’s lights.

Many of the works in these exhibitions reflect such a process of assimilation. Fine—whose 1949 canvas, The Forest, is on view at Spanierman—once told me that her spare linear imagery was indirectly influenced by the winter landscape, in which the dark verticals of tree trunks are foiled against the snow’s whiteness. Parsons’ ambiguously titled Blue Field, also at Spanierman,could refer to a farm field like the ones near her Southold home, or to the background that supports her abstract motifs. In the Findlay show, the gnarled forms in Slivka’s energetic ink drawings have their counterparts in chunks of driftwood, and in tree roots exposed by erosion on the coastal bluffs. Similarly, Pavia’s late 1940s bronzes suggest fragments of structures weathered by wind, sand and sea. The celestial allusions in Lassaw’s open-space sculptures—like Callisto [right], named for one of Jupiter’s moons—became more frequent after he began summering in Springs, where the night sky was not obscured by the city’s lights.

As these two shows demonstrate, it isn’t only landscape painters who are inspired by the East End environment. For abstract artists, it may be a mood, a feeling, a sensation that makes the creative juices flow, prompting responses to natural phenomena that are all the more evocative for being abstract.

Glimpsing de Kooning at MoMA

09-22-2011

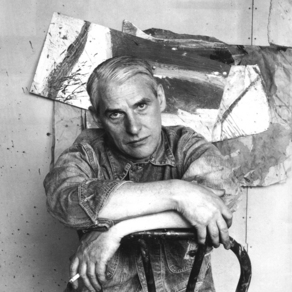

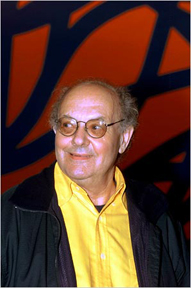

Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) [left] famously referred to himself as “a slipping glimpser,” a painter who paradoxically felt most comfortable when he was off balance. “When I’m falling,” he said, “I am doing all right. And when I am slipping, I say, ‘Hey, this is very interesting.’” He made that remark in 1960, roughly midway through a seven-decade career that is now the subject of a long-overdue survey at the Museum of Modern Art. To paraphrase the artist, it’s very interesting that for decades he slipped past the glimpse of the normally eagle-eyed MoMA curators, who focused instead on his contemporaries among the New York School vanguard. This show (on view through January 9) redresses that imbalance.

Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) [left] famously referred to himself as “a slipping glimpser,” a painter who paradoxically felt most comfortable when he was off balance. “When I’m falling,” he said, “I am doing all right. And when I am slipping, I say, ‘Hey, this is very interesting.’” He made that remark in 1960, roughly midway through a seven-decade career that is now the subject of a long-overdue survey at the Museum of Modern Art. To paraphrase the artist, it’s very interesting that for decades he slipped past the glimpse of the normally eagle-eyed MoMA curators, who focused instead on his contemporaries among the New York School vanguard. This show (on view through January 9) redresses that imbalance.

Balance is a metaphor for the exhibition itself, and (notwithstanding his disclaimer) for de Kooning’s artistic enterprise. The show maintains its equilibrium by presenting his seesaw shifts from representation to abstraction in parallel rather than divergent courses. The earliest works, from his native Holland and soon after his emigration in 1926, make it clear that even when he was working as a commercial artist and decorator he was simultaneously a skillful academic draftsman and a keen observer of modern art trends. With equal assurance he could render a still life accurately, or abstract it à la Matisse.

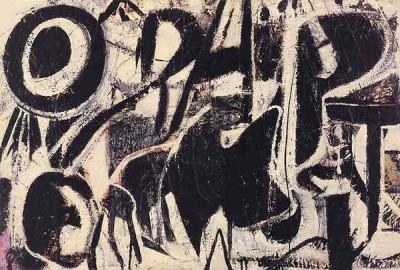

In the 1930s the WPA Federal Art Project enabled de Kooning to quit his day job and concentrate on fine art. Alternating between figure study and non-objective formalism, his paintings, mural studies and drawings of the period continue a dialogue that aims to resolve this dichotomy—an endeavor that fortunately never succeeded. At a time when purists insisted on an either-or approach, he was unwilling to take sides. In 1947-48, when the argument was at its most intense, he was painting stark black and white abstractions like Orestes [1947, right] and Dark Pond while also coming out with his second Woman series, represented here by Pink Lady, Woman and several works on paper.

In the 1930s the WPA Federal Art Project enabled de Kooning to quit his day job and concentrate on fine art. Alternating between figure study and non-objective formalism, his paintings, mural studies and drawings of the period continue a dialogue that aims to resolve this dichotomy—an endeavor that fortunately never succeeded. At a time when purists insisted on an either-or approach, he was unwilling to take sides. In 1947-48, when the argument was at its most intense, he was painting stark black and white abstractions like Orestes [1947, right] and Dark Pond while also coming out with his second Woman series, represented here by Pink Lady, Woman and several works on paper.

I’m far from alone in believing that 1948-1955 marks the high point of de Kooning’s achievement, and this exhibition hasn’t changed my mind. The masterpieces from those years are here in force, including Excavation, Attic and Asheville, supreme demonstrations of his ability to combine observation, sensation and invention, and six of the monstrous (and monstrously controversial) Woman paintings that to this day divide de Kooning’s admirers and detractors. Volumes have already been written about these grotesques; suffice it to say that they’ve never looked better than they do here, lined up like beauty pageant contestants from Hell.

I’m far from alone in believing that 1948-1955 marks the high point of de Kooning’s achievement, and this exhibition hasn’t changed my mind. The masterpieces from those years are here in force, including Excavation, Attic and Asheville, supreme demonstrations of his ability to combine observation, sensation and invention, and six of the monstrous (and monstrously controversial) Woman paintings that to this day divide de Kooning’s admirers and detractors. Volumes have already been written about these grotesques; suffice it to say that they’ve never looked better than they do here, lined up like beauty pageant contestants from Hell.

For whatever psychological or aesthetic reasons, the distorted female figure continued to preoccupy de Kooning for decades, but in tandem with compositions that lack overt figurative references. Not that the real world was excluded from canvases like Gotham News and Easter Monday, in which he retained offset text and photos from the newspapers he used to blot the surface. As with the Women, where schematic but recognizable body parts give coherence to what otherwise would look like disorganized explosions of paint, these fragments anchor the abstractions in familiar imagery.

It seems to me that de Kooning’s entire career was a balancing act. Or maybe a pendulum, with its regular alternation from one extreme to the other, is a better analogy. As visitors progress through the selection of some 200 paintings, drawings, sculptures and prints in MoMA’s brilliantly installed sixth-floor galleries, the artist’s clock winds down and the swings become less pronounced, until they resolve in a series of biomorphic abstractions that distill the essence of his vision. Toward the end, his glimpse slipped ever more inward. But this exhibition doesn’t tell the whole story of that interior journey. The curator, John Elderfield, chose to exclude work from 1988-90, the last three years of de Kooning’s productive life, when he painted more than 50 canvases while succumbing to senile dementia. A full retrospective assessment won’t be possible until those paintings are seen.

It seems to me that de Kooning’s entire career was a balancing act. Or maybe a pendulum, with its regular alternation from one extreme to the other, is a better analogy. As visitors progress through the selection of some 200 paintings, drawings, sculptures and prints in MoMA’s brilliantly installed sixth-floor galleries, the artist’s clock winds down and the swings become less pronounced, until they resolve in a series of biomorphic abstractions that distill the essence of his vision. Toward the end, his glimpse slipped ever more inward. But this exhibition doesn’t tell the whole story of that interior journey. The curator, John Elderfield, chose to exclude work from 1988-90, the last three years of de Kooning’s productive life, when he painted more than 50 canvases while succumbing to senile dementia. A full retrospective assessment won’t be possible until those paintings are seen.

Sol LeWitt at Mass MoCA: Worth the Trip

08-18-2011

At this point in the summer we could all use a break from the seasonal craziness of The Hamptons. I suggest you hop in the car and take the ferry to New London. Then breeze through The Other Hamptons (Southampton, Easthampton and Northampton, MA, that is) en route to the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art, better known as Mass MoCA, in North Adams. There you’ll find an extraordinary installation celebrating the life work of Sol LeWitt, one of the pioneers of conceptual art.

LeWitt [right] made his first wall drawing more than forty years ago at the Paula Cooper Gallery in Manhattan—his first, and in a sense, his last, because after that he no longer drew them himself. Instead he produced sets of instructions for other people to follow, like scores that a composer writes for other musicians to play. When collectors buy his work, they buy the visual-art equivalent of sheet music. He was less interested in the art object than in the idea behind it, which he called “a machine that makes the art,” although in truth it takes a lot of hand labor to create the finished product.

LeWitt [right] made his first wall drawing more than forty years ago at the Paula Cooper Gallery in Manhattan—his first, and in a sense, his last, because after that he no longer drew them himself. Instead he produced sets of instructions for other people to follow, like scores that a composer writes for other musicians to play. When collectors buy his work, they buy the visual-art equivalent of sheet music. He was less interested in the art object than in the idea behind it, which he called “a machine that makes the art,” although in truth it takes a lot of hand labor to create the finished product.

For his Mass MoCA retrospective, scores of drafters spent months executing nearly ninety of them on all three floors of a specially renovated 27,000 square-foot former factory building. This extremely ambitious project is a collaboration among Mass MoCA, the Yale University Art Gallery and Williams College Museum of Art. Teams of students from both schools filled acres of custom-built walls according to LeWitt’s instructions. Sadly, the artist who dreamed up this prodigious body of work didn’t live to see the ensemble completed. He died in 2007, so the exhibition is a memorial that spans his entire conceptual output.

It’s inevitable, given the wide scope of his imagination, that some examples are more appealing than others. I’m partial to the early work, with its spare geometry, muted colors and formal rigor. Those pieces are on the first floor, and they include the fascinating Wall Drawing 51 [left], first drawn in 1970 and made entirely of blue lines created by snapping chalked string that was stretched between all the architectural points on the wall—from the corner of a window to the corner of a door, for example. The result is a complex web of linear marks that articulates the wall surface in surprising, and surprisingly beautiful, ways. And it would be completely different on different walls. The instructions don’t vary, but the results on each wall are unique.

It’s inevitable, given the wide scope of his imagination, that some examples are more appealing than others. I’m partial to the early work, with its spare geometry, muted colors and formal rigor. Those pieces are on the first floor, and they include the fascinating Wall Drawing 51 [left], first drawn in 1970 and made entirely of blue lines created by snapping chalked string that was stretched between all the architectural points on the wall—from the corner of a window to the corner of a door, for example. The result is a complex web of linear marks that articulates the wall surface in surprising, and surprisingly beautiful, ways. And it would be completely different on different walls. The instructions don’t vary, but the results on each wall are unique.

This floor also features another of my favorites [right, during the remaking process], Wall Drawing 797, a 1995 piece that starts with a meandering horizontal line near the top of the wall, drawn by one person using a black marker. Then another person draws a parallel line just below it, using a red marker. Then another person draws a parallel yellow line below the red one. The next line is blue, then red again, then yellow, and so on. Eventually the wall is filled with an undulating curtain of colored stripes, because the freehand lines don’t follow the preceding ones exactly.

This floor also features another of my favorites [right, during the remaking process], Wall Drawing 797, a 1995 piece that starts with a meandering horizontal line near the top of the wall, drawn by one person using a black marker. Then another person draws a parallel line just below it, using a red marker. Then another person draws a parallel yellow line below the red one. The next line is blue, then red again, then yellow, and so on. Eventually the wall is filled with an undulating curtain of colored stripes, because the freehand lines don’t follow the preceding ones exactly.

The upper floors are a riot of color, and to my taste the drawings lose some of their interest as they become ever more like hard-edged super graphics. They kind of hit you in the eye, rather than seducing you with subtlety, but if you prefer jazzy colors, bold shapes and decorative effects, you have them in abundance. The late works, however, go back to simple graphite pencil lines on white walls, re-emphasizing the hand-made quality that’s so attractive in the earlier pieces. At the end of his life, Sol LeWitt returned to first principles.

Theft: A Love Story

07-21-2011

As a summer read for those who believe that the art world is less than scrupulous, I recommend Peter Carey’s wickedly entertaining novel, Theft, subtitled A Love Story, in which everyone is a crook. The primary narrator, a washed-up Australian painter named Michael Boone (alias Butcher Bones) steals from his patron, who has stolen Michael’s wife. The ex-wife, Michael believes, has stolen his paintings, as well as their son, in the divorce settlement. Michael, in turn, steals someone else’s wife, Marlene Liebowitz, who steals anything that isn’t nailed down. Even the detective who pursues her reveals himself as a petty thief. Dealers steal from artists, collectors steal from dealers, and so it goes, right down to the New York taxi drivers who rob Butcher of his equilibrium, or at least give him someone else to blame for his agitation and clouded judgment.

As a summer read for those who believe that the art world is less than scrupulous, I recommend Peter Carey’s wickedly entertaining novel, Theft, subtitled A Love Story, in which everyone is a crook. The primary narrator, a washed-up Australian painter named Michael Boone (alias Butcher Bones) steals from his patron, who has stolen Michael’s wife. The ex-wife, Michael believes, has stolen his paintings, as well as their son, in the divorce settlement. Michael, in turn, steals someone else’s wife, Marlene Liebowitz, who steals anything that isn’t nailed down. Even the detective who pursues her reveals himself as a petty thief. Dealers steal from artists, collectors steal from dealers, and so it goes, right down to the New York taxi drivers who rob Butcher of his equilibrium, or at least give him someone else to blame for his agitation and clouded judgment.

Michael’s mentally retarded brother Hugh—or Slow, as his nickname has it—steals more benignly, almost by default. His is the other narrative voice, a dark, distorted echo of his brother’s. He reminds me of John Steinbeck’s Lenny in Of Mice and Men: large, strong and volatile, a protector and an avenger. His crime is to witness the fraud and deception all around him, which makes him potentially even more dangerous. In a sense, you might say that he steals the truth and stores it away in his poor, addled brain. Occasionally it comes spilling out, and that’s always messy.

This larcenous tale is set in the art world of the early 1980s, when Michael’s star is most definitely on the wane. Now in his late 30s, he’s already a has-been in the insular Australian art market, where he was a big noise ten years earlier. In fact this son of a provincial butcher had a phenomenal run of luck—escaping the family business, which his rough-hewn father was grooming him to inherit (hence his nickname), then actually achieving some measure of success as an artist, even if only in his homeland. But Michael is mordantly bitter, self-flagellating and comically hapless, a cross between Kurt Vonnegut’s Rabo Karabekian and Gulley Jimson, the charming scoundrel who stars in The Horse’s Mouth, by the Irish novelist Joyce Cary—related to Peter Carey only in his gift for brilliantly capturing his central character’s foibles.

The plot hinges on the theft of a very valuable painting by Marlene’s long-dead father-in-law—a cubist ranked right up there with Picasso and Braque—and the disappearance of another of his masterpieces. It has a couple of unlikely twists, which I won’t give away, although I will say that the ending is a bit too pat for my taste. The book’s real rewards are in the reading itself, in Carey’s use of language, although much of it is unquotable here. The text is heavily larded with vulgarity and profanity, an earthy tone that suits the characters perfectly. It also cleverly masks the quicksilver turns of phrase and the dead-on aperçus that give Carey’s writing its punch.

When Marlene wangles a solo exhibition for Michael in Tokyo, he fantasizes that it will be the ticket to his ultimate destination, the top of the New York art heap. In fact, the show is not so much his comeback as his payback for the enormous favor he’s about to do for Marlene, who has a vested interest in, shall we say, his success. In the end, the artist is nothing more than a hired gun, producing to order what he thinks, or knows, will please his client. That his client happens to have stolen his heart is a minor complication.

In their odyssey from Sydney to SoHo, Michael discovers the true extent of Marlene’s thievery, but along the way he accumulates a raft of insights—none of which are of any use to him. Time, the greatest thief of all, teaches him nothing.

Abstract Expressionism Lives On

06-23-2011

Last month a panel was convened in Franklin Lakes, New Jersey, to discuss the current state of the art world in general, and in particular whether the approach known as Abstract Expressionism is still relevant in the 21st century. The hosts, Tom and Marika Herskovic, are art collectors who specialize in that genre and have published three books on the subject. They asked me to moderate the discussion, which ranged from nostalgia for the good old days 60 years ago, when Ab Ex reigned supreme, to despair over the emotional vacancy of much contemporary art, but was not without a hopeful outlook for the future.

The pioneering Abstract Expressionists are no longer with us, but the Museum of Modern Art’s recent blockbuster collection show signaled that they’re definitely not forgotten, as well as proving that they had successors. Panelists George Ortman and Sonia Gechtoff, both born in 1926, represented the next generation. They were just coming of age when The New Yorker’s art critic, Robert Coates, decided that Abstract Expressionism was a more polite label for what others had derisively called “the spatter-and-daub school.” Attacking a bone of contention that was first chewed on back in the day, neither veteran could come up with a clear definition of the term. Ortman emphasized the fact that, although it’s often hailed as a purely American phenomenon, Ab Ex was really an outgrowth of European Surrealism, with all its literary and narrative baggage, while Gechtoff maintained that its most important characteristic was a total lack of representational content. It was, she insisted, “about nothing but the painting itself.”

Other panelists, including relatives of deceased artists like Nicolas Carone, John Hultberg and Michael Goldberg—members of the sizeable Ab Ex contingent that frequented the Hamptons in the 1950s—gamely weighed in but failed to arrive at a consensus. If there was agreement, it was that while there’s no such thing as an Abstract Expressionist style, the common denominators are subjectivity, improvisation and inner vision. Hultberg’s partner, Elaine Weschler, called it “emotional shorthand,” and Christian Carone pointed out that his father, a former Springs resident who died last year, relied on imagination rather than observation for his imagery, even when faces or figures appeared [see example below]. To the artist Rudy Ernst (no relation to Max, Jimmy and Eric), Abstract Expressionism is the “rendering of personality.”

Several panelists complained about the superficiality of current gallery fare, but I saw the prospect of a resurgence of individuality and feeling. During the week or so before the panel, I had encountered artists from Finland, Hungary and China who enthusiastically self-identified as Abstract Expressionists. It struck me that one of the movement’s original aims—the invention of what the artist Alfonso Ossorio described as “an international language of the brush”—had been fulfilled. And far from being a historical phenomenon that went out with tail fins and transistor radios, Ab Ex seems to me to have staying power.

Among the younger generation of artists, Sam Rivers—Larry Rivers’ youngest son and, at age 25, the youngest panelist—believes that the spirit is alive and well among artists for whom emotion and experimentation are paramount. While allowing that it’s no longer mainstream, he and Anki King, a 40 year old Norwegian-American painter whose symbolic figures embody “feelings that can’t accurately be described in words,” agreed that Abstract Expressionism is still valid, and that it offers a rewarding alternative to the slick merchandise that dominates today’s art market.

Nicolas Carone, Shadow Dance, 2007, Acrylic on canvas, 84 x 119-3/4 inches. Courtesy Washburn Gallery, New York.

Imago ad Absurdum

05-26-2011

Not so long ago, the idea of a photograph selling for a million dollars seemed absurd. Why would anyone pay that much for a reproduction? But, for the sake of argument, if someone did, what sort of picture would it be? Well, a rare vintage print, maybe one of a kind, personally made in the darkroom by a master like Alfred Stieglitz or Ansel Adams, of course. At least that was the prediction, which just goes to show that you can’t trust the ol’ crystal ball.

In fact, the first million-dollar photo was anything but a unique vintage masterpiece. It was one of Richard Prince’s “Cowboy’ series—a so-called rephotograph of a Marlboro cigarette ad [left]—that hit the million-point-two mark in a 2005 auction. Prince, who will be having a solo exhibition at Guild Hall Museum this summer, takes pictures of other people’s pictures and passes them off as his own work. If I did that with other people’s words it would be called plagiarism, but in the art world there’s a long tradition of this kind of unauthorized and uncredited borrowing. Heck, Andy Warhol made a fortune doing it, and Prince is on the same career path, although he suffered a detour in March, when a U.S. District judge ruled against him and his dealer, Larry Gagosian, in a copyright infringement suit brought by a French photographer, Patrick Cariou, whose pictures were “appropriated” by Prince without permission.

In fact, the first million-dollar photo was anything but a unique vintage masterpiece. It was one of Richard Prince’s “Cowboy’ series—a so-called rephotograph of a Marlboro cigarette ad [left]—that hit the million-point-two mark in a 2005 auction. Prince, who will be having a solo exhibition at Guild Hall Museum this summer, takes pictures of other people’s pictures and passes them off as his own work. If I did that with other people’s words it would be called plagiarism, but in the art world there’s a long tradition of this kind of unauthorized and uncredited borrowing. Heck, Andy Warhol made a fortune doing it, and Prince is on the same career path, although he suffered a detour in March, when a U.S. District judge ruled against him and his dealer, Larry Gagosian, in a copyright infringement suit brought by a French photographer, Patrick Cariou, whose pictures were “appropriated” by Prince without permission.

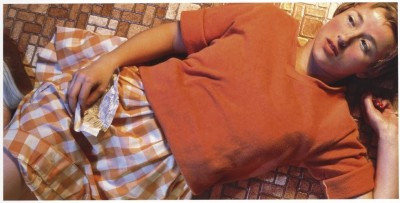

In the pricey photographs market, however, no one tops Cindy Sherman. Two weeks ago at Christie’s New York, one of her role-playing self-portraits sold for an astonishing $3.9 million, reportedly the highest price ever paid for a photograph. And, even more amazing, it’s one of ten prints of the same image. The owners of the other nine must be in hog heaven. Sherman, who has a home in Sag Harbor, made her name over 30 years ago with a series of 8 x 10 black and white photos that mimicked stills from B movies, all featuring herself playing the Central Casting characters. They’re basically costume pieces, and their interest is in how they comment on pop-culture female stereotypes.

Her next move, in the early 1980s, was to make them bigger and do them in color—the 1981 record-breaker [below] is an early example. If we wanted to be here all day, we could debate the artistic merits of this picture, we could discuss its crossover from low to high culture status, and we could consider what its high price says about the current state of the art market. But none of those issues addresses its monetary value. I’m hardly the first person to point out that, as far as intrinsic value is concerned, art has none. It’s worth whatever someone is willing to pay for it. Unfortunately all those dollar signs form a barrier that blocks the view and make it hard to draw a distinction between the photograph as an image of significance and as an object of acquisitive desire.

There was a time when originality and innovation were major indicators of art’s value, but those days are long gone. When copying went from being a training exercise to an end in itself, uniqueness lost traction. I don’t want to sound grumpy—as a matter of fact, I agree with Marcel Duchamp that art is whatever the artist says it is—but I begin to have a problem when price eclipses merit as a benchmark of quality. Still, it’s good to put everything in perspective. Lots of yesterday’s overpriced trophies are now languishing in museum basements, and we may live to see the day when, like the housing bubble, the photography bubble bursts and (if you’ll forgive the pun) Sherman tanks.

There was a time when originality and innovation were major indicators of art’s value, but those days are long gone. When copying went from being a training exercise to an end in itself, uniqueness lost traction. I don’t want to sound grumpy—as a matter of fact, I agree with Marcel Duchamp that art is whatever the artist says it is—but I begin to have a problem when price eclipses merit as a benchmark of quality. Still, it’s good to put everything in perspective. Lots of yesterday’s overpriced trophies are now languishing in museum basements, and we may live to see the day when, like the housing bubble, the photography bubble bursts and (if you’ll forgive the pun) Sherman tanks.

Cindy Sherman, Untitled #96, 1981. Color coupler print, 24 x 48 inches.

Protest Art: China vs. America

04-28-2011

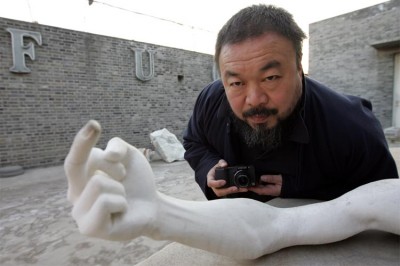

A few days ago I got an email from my friend Gail Pellett, a documentary film maker who has a house on Three Mile Harbor, about the plight of the Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei. He was arrested at Beijing airport on April 3 and is being held incommunicado on charges that range from tax evasion to bigamy. Gail met Ai in China in 1980, when she was working as an editor for Radio Beijing. He was then a young rebel affiliated with an avant-garde group called Star Star, which rose and fell with the New Democracy movement. The following year he moved to New York, where several Star Star alumni had migrated. He lived in the East Village, enrolled in Parsons School of Design, and met up with Gail again. In an article she wrote about the expats for The Village Voice in 1985, she quoted Ai as describing them as “the scorched flowers of China.”

Since then, Ai has become an internationally celebrated figure, known for his outspoken cultural critiques, provocative installations, and running around with no clothes on. He delights in disparaging authority and saluting power with his middle finger, yet he was invited to design the National Stadium, famous as the Bird’s Nest, for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. His apparent endorsement by the Chinese government seemed to augur well for a new era of openness, but over the past few years they’ve been clamping down on him and other artists who have stepped over the so-called red line of official tolerance.

Since then, Ai has become an internationally celebrated figure, known for his outspoken cultural critiques, provocative installations, and running around with no clothes on. He delights in disparaging authority and saluting power with his middle finger, yet he was invited to design the National Stadium, famous as the Bird’s Nest, for the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing. His apparent endorsement by the Chinese government seemed to augur well for a new era of openness, but over the past few years they’ve been clamping down on him and other artists who have stepped over the so-called red line of official tolerance.

The recent unrest in the Middle East has accelerated efforts to stifle freedom of expression in China. Ai’s high status on the global art stage didn’t insulate him against what everyone from Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Václav Havel and the European Union has condemned as a blatant attempt to muzzle dissent. His arrest, following earlier incidences of police brutality, detention, and the demolition of his Shanghai studio, appears to be related to calls for a “jasmine revolution” inspired by regime change in Egypt and Tunisia. Fearful of his potential endorsement of such a movement, the authorities are holding him at an undisclosed location. In a cynical effort to disguise their true motives, they accuse him of “economic crimes” and deny charges of censorship. Since creativity has yet to be criminalized in China (wait for it), they came up with something illegal to charge him with.

In the United States, by contrast, even art that is in fact illegal gets the official stamp of approval. I was amused to read an article in last Sunday’s New York Times about a show of graffiti at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art, organized by the museum’s controversial director, former art dealer Jeffrey Deitch. Although he looks like a Harvard MBA—which he is—Deitch is no strait-laced suit. Known for his promotion of street art at his now-defunct New York gallery, Deitch Projects, he delights in the outrageous, like exhibiting a burned-out meth lab as a sculpture installation. Other people get arrested for having a meth lab, but Deitch gets reviewed in the art press.

Wall-tagging and subway-car defacement—quintessential expressions of urban protest—are also frowned on by law enforcement, but when they’re enshrined in LACMA they’re more than just sanctioned, they’re defanged. They become, as the LA Times aptly put it, “eye-candy.” In the art world and the real world, if the powers that be embrace transgression, it loses its power to threaten. For a while it seemed as if the Chinese authorities had learned that lesson, but apparently not.

Cézanne’s Card Players: Asleep at the Deal

03-31-2011

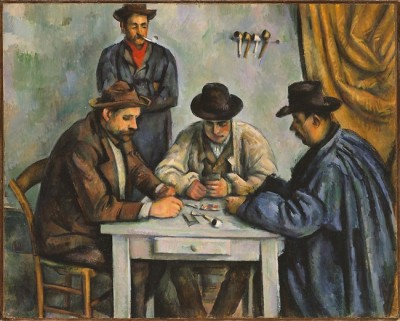

If you take a right turn off the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Greek and Roman galleries, you’ll find three small rooms devoted to focused temporary exhibitions. The current show, on view through May 8, brings together many of the paintings and drawings of card players by Paul Cézanne, whose fans included just about every pioneer of 20th century modernism. Made in the 1890s on his family’s estate near Aix-en-Provence, the series illustrates his fascination with the timeless character of peasant life. He once said, “I love above all else the appearance of people who have grown old without breaking with old customs,” an odd sentiment for someone who broke with nearly all the old customs in painting’s rulebook.

For those who are interested in how the curatorial mind works, this show is an object lesson, both positive and negative. First the bad news. Operating on the premise that everyone is dying to know the order in which each painting or drawing may have been produced, which one may be a study for, or tracing of, another, as well as other conjectures, the organizers have written mind-numbing label copy. Playing that guessing game may be fun for hair-splitting scholars, but it contributes nothing to an appreciation of the art itself. Nor it is helpful that the two largest paintings from the series are missing. (In The New York Times, Karen Rosenberg quipped that the show is an “incomplete deck.”) Even the Met’s formidable leverage wasn’t enough to pry loose the Barnes Foundation’s example—which will only travel when that fabled collection moves from Merion to Fairmont Park next year—and a sibling canvas from a private collection. So they’re reproduced at full size, but in dull black and white. Evidently the curators think we can’t tell the difference between a color print of a painting and the real thing.

In spite of these shortcomings, the exhibition illuminates certain aspects of Cézanne’s achievement and offers a revealing look into his aims. A selection of prints from the Met’s collection shows how his Dutch, French and English predecessors depicted card playing—an inspired curatorial decision that underscores how different Cézanne’s approach was. Instead of scenes of rowdy gamblers in taverns, often with implicit moralistic messages, he gives us straightforward studies of rustic workers, presumably relaxing after a day’s hard labor on the estate. He was well aware of the genre tradition, but he wasn’t aiming for social critique or satire. His subjects were the salt of the earth—he admired their peasant simplicity (perhaps a bit condescendingly) and their stoicism, which are evident in his treatment of their figures.

Each man is presented as a solitary, self-contained individual, absorbed in studying his hand and ignoring his companions. They’re sitting so still that they might be asleep, and even the guy watching the game in a couple of the versions looks like he’s in a trance. It seems that they aren’t even gambling—there are no stakes on the table. This preternatural stillness robs the figures of vitality and forces you to see them as objects rather than subjects. Apparently Cézanne was more interested in studying and organizing their forms, and the space around them, than in either their personalities or what they were doing. His statement about loving the appearance of people is telling; he loved what they looked like, not who they were. He was intrigued by the way one man’s sleeve folded at the elbow and by the pleats in his smock, by how another man’s hat brim curled, by the contrast of a bent knee’s roundness with the sharp angle of a table leg. All this analyzing led to paintings that are neither genre scenes nor portraits. They’re about solving the formal problems of painting itself, which is what makes them so modern.

Each man is presented as a solitary, self-contained individual, absorbed in studying his hand and ignoring his companions. They’re sitting so still that they might be asleep, and even the guy watching the game in a couple of the versions looks like he’s in a trance. It seems that they aren’t even gambling—there are no stakes on the table. This preternatural stillness robs the figures of vitality and forces you to see them as objects rather than subjects. Apparently Cézanne was more interested in studying and organizing their forms, and the space around them, than in either their personalities or what they were doing. His statement about loving the appearance of people is telling; he loved what they looked like, not who they were. He was intrigued by the way one man’s sleeve folded at the elbow and by the pleats in his smock, by how another man’s hat brim curled, by the contrast of a bent knee’s roundness with the sharp angle of a table leg. All this analyzing led to paintings that are neither genre scenes nor portraits. They’re about solving the formal problems of painting itself, which is what makes them so modern.

Paul Cézanne (1839–1906), The Card Players, ca. 1890–92. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Stephen C. Clark.

The Watchcase Factory—Think Creative

02-03-2011

Four years ago, Cape Advisors, a Manhattan real estate developer, unveiled the latest of several plans to come down the pike—East Hampton-Sag Harbor Turnpike, that is—for renovation of the former Bulova watchcase factory [left], the once-proud 19th century industrial building in the heart of the village that’s now a crumbling eyesore. The proposal, which called for 63 luxury condominium apartments and 18 town house units, was approved by the zoning board in August 2008. But the venture ground to a halt when the real estate bubble burst and the sponsoring group, now known as Sag Development Partners, lost steam. Maybe that’s just as well, since there was considerable public dissent during the review process, focusing on the lack of affordable housing units mandated by the Suffolk County Planning Commission. So let’s rethink the project, this time a bit more creatively—and I mean that literally.

Four years ago, Cape Advisors, a Manhattan real estate developer, unveiled the latest of several plans to come down the pike—East Hampton-Sag Harbor Turnpike, that is—for renovation of the former Bulova watchcase factory [left], the once-proud 19th century industrial building in the heart of the village that’s now a crumbling eyesore. The proposal, which called for 63 luxury condominium apartments and 18 town house units, was approved by the zoning board in August 2008. But the venture ground to a halt when the real estate bubble burst and the sponsoring group, now known as Sag Development Partners, lost steam. Maybe that’s just as well, since there was considerable public dissent during the review process, focusing on the lack of affordable housing units mandated by the Suffolk County Planning Commission. So let’s rethink the project, this time a bit more creatively—and I mean that literally.

Last week I attended a forum, with the catchy title “Promoting the Arts, Cultural Institutions and Historic Sites,” sponsored by Senator Kirsten Gillibrand’s office. Representatives from arts organizations all around the Island met at the Patchogue Theatre to learn how we can take advantage of public funding opportunities. Those of us who till the creative fields know how much the arts contribute to the regional economy, as well as the less tangible quality-of-life benefits. But you can’t have a thriving, diverse arts community without affordable places for artists to live and work. That’s an issue the Village of Patchogue is addressing, and the Village of Sag Harbor just might want to listen up.

The forum’s afternoon session featured a presentation by Shawn McLearen, representing Artspace, a Minneapolis-based nonprofit real estate developer for the arts. Artspace owns and operates 27 projects in 19 cities, from Seattle to Bridgeport. Twenty-one of them are live/work projects, mostly in renovated buildings like factories, schools, warehouses, and even an old army base, with a total of nearly a thousand residential units. Many also include offices for arts organizations, rehearsal and performance venues, and commercial space for arts-friendly businesses.

A few years ago, Artspace partnered with the Patchogue Village Community Development Agency, the Chamber of Commerce, the Business Improvement District, the Patchogue Arts Council (yes, the village has its own arts council) and other groups to create affordable residential workspaces for artists and their families. The fruit of that labor—Artspace Patchogue Lofts, a five-story, 45-unit complex on Terry Street—is due to open this spring. Unlike most Artspace projects it’s new construction, a sleek modern building with an $18 million price tag financed by a combination of corporate, foundation and government grants, loans, gifts, and economic development funds. If you don’t want to drive the 50 miles to Patchogue to check it out, you can see it on their website, www.artspace.org.

Interestingly, although preference is given to applicants who “participate in and are committed to the arts,” anyone who qualifies for affordable housing may apply. So while Artspace is focused on serving artists, it doesn’t exclude others. The Patchogue project has had 75 applications so far, and is still accepting them, so if you can’t wait for the watchcase factory to become an Artspace project, you can download the application form.

While you’re on the website, take a look at some of the industrial and commercial rehab projects, like the Northern Warehouse in St. Paul, the Harvester Lofts in Council Bluffs, and especially the Switching Station in Chicago [right], and see if they remind you of a building closer to home—on Hampton Street, in fact. Sag Harbor may not have an arts council, but it does have a Community Housing Trust that could work with Artspace, the Long Island Housing Partnership, the Suffolk County Office of Economic Development and Workforce Housing, CONPOSH, Save Sag Harbor and other interested parties to rescue the watchcase factory and transform it into a hive of creative activity, as well as a monument to creative thinking.

While you’re on the website, take a look at some of the industrial and commercial rehab projects, like the Northern Warehouse in St. Paul, the Harvester Lofts in Council Bluffs, and especially the Switching Station in Chicago [right], and see if they remind you of a building closer to home—on Hampton Street, in fact. Sag Harbor may not have an arts council, but it does have a Community Housing Trust that could work with Artspace, the Long Island Housing Partnership, the Suffolk County Office of Economic Development and Workforce Housing, CONPOSH, Save Sag Harbor and other interested parties to rescue the watchcase factory and transform it into a hive of creative activity, as well as a monument to creative thinking.

Hot Books for Cold Weekends

01-06-2011

On a cold winter weekend, what could be better than a hot book? The two I have in mind aren’t hot in the best-seller sense, since they’ve been around for a while. You’ll have to call the John Jermain Library and order them through inter-library loan, or you can find them for sale on the Internet, in either the original hardcover editions or paperback reissues. These books are hot in the other metaphorical sense, dealing as they do with the sex lives of two of the art world’s most colorful female characters. No bodices are ripped—these gals willingly shed their garments.

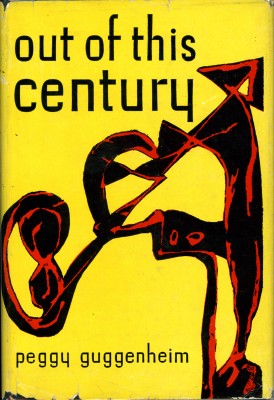

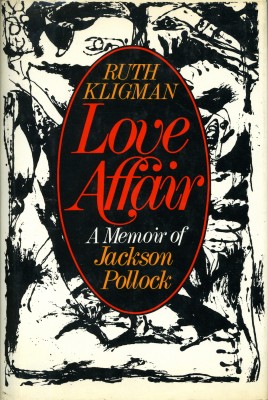

The gals in question are the celebrated art collector Peggy Guggenheim, whose memoir, Out of This Century, with a jacket design by Jackson Pollock, was published by Dial Press in 1946, and Ruth Kligman, mistress to the stars and author of Love Affair: A Memoir of Jackson Pollock, published in 1974 by William Morrow. Kligman added a preface in 1999, when her book was republished in paperback by Cooper Square Press. Guggenheim updated hers in 1960 and again in 1979, when Macmillan brought it out as Confessions of an Art Addict.

Guggenheim has been the subject of three biographies, but no one tells her story with the verve and candor that she brings to the saga of her scandalous escapades as an expatriate heiress in interwar Europe, where her modest fortune went much further than in her native New York City. It financed a bibulous social life, complete with a cast of world-class eccentrics, adulterous liaisons, verbal (and sometimes physical) conflict, and whirlwind travels punctuated by the acquisition of a fabulous collection of modern art. Peggy chronicles it all breathlessly, often at her own expense. When the book was first published, her horrified family reportedly said it should have been titled Out of Her Mind, and tried to buy up all the copies.

She came into her inheritance at the age of 21, just as World War I ended, and within a year was in Paris, where she lost her virginity to Laurence Vail, a neurotic, alcoholic would-be writer and artist whom she called the King of Bohemia. In the original 1946 edition, she identifies him by the pseudonym “Florenz,” an odd conceit considering that he was well known as her first husband and the father of her two children. Some of her other lovers who were then living are discreetly disguised—Samuel Beckett as “Oblomov,” Douglas Garman as “Sherman” and Marcel Duchamp as “Luigi,” for example—while others, even those inconveniently married to other women, are allowed to sail under their own colors.

She came into her inheritance at the age of 21, just as World War I ended, and within a year was in Paris, where she lost her virginity to Laurence Vail, a neurotic, alcoholic would-be writer and artist whom she called the King of Bohemia. In the original 1946 edition, she identifies him by the pseudonym “Florenz,” an odd conceit considering that he was well known as her first husband and the father of her two children. Some of her other lovers who were then living are discreetly disguised—Samuel Beckett as “Oblomov,” Douglas Garman as “Sherman” and Marcel Duchamp as “Luigi,” for example—while others, even those inconveniently married to other women, are allowed to sail under their own colors.

During World War II, people named Guggenheim were not welcome in Hitler’s domain, so Peggy returned to New York with her art collection and a retinue that included her current lover (soon to be husband number two), the Surrealist painter Max Ernst. In New York she opened a gallery, Art of This Century, which showcased her treasure trove of abstract and Surrealist art, as well as local talent of the vanguard persuasion. Among her discoveries was the then-unknown Jackson Pollock, who became her protégé. The Pollock biopic, starring Ed Harris as the artist and his off-screen wife, Amy Madigan, as Peggy, gives them an abortive love scene, but if such an encounter did occur the memoir is uncharacteristically silent on the matter. Indeed, in the expanded version, written after Pollock’s death, Peggy describes their relationship as “purely that of artist and patron.” Whether that implies any extracurricular duties on his part is left to the reader’s imagination—just about the only thing in this tell-all that is.

Kligman’s book, on the other hand, leaves no doubt that her knowledge of Pollock was carnal; the title alone makes that clear. By turns gushingly romantic, deeply delusional and painfully conflicted, it describes her brief, turbulent involvement with the artist at the end of his career—in fact, at the end of his life. They met in the spring of 1956 at the Cedar Bar, the artists’ hangout in Greenwich Village, where a drunken Pollock would bait his colleagues and make passes at their dates. Even though, mired in alcoholism, he was no longer painting, he was still top dog among the abstract expressionists. An aspiring artist herself, Ruth (18 years his junior) was star-struck. She threw herself at him, and to no one’s surprise—except maybe Pollock’s—he caught her. After a steamy encounter in her apartment, they declared their mutual love, and the affair was off and running.

Kligman’s book, on the other hand, leaves no doubt that her knowledge of Pollock was carnal; the title alone makes that clear. By turns gushingly romantic, deeply delusional and painfully conflicted, it describes her brief, turbulent involvement with the artist at the end of his career—in fact, at the end of his life. They met in the spring of 1956 at the Cedar Bar, the artists’ hangout in Greenwich Village, where a drunken Pollock would bait his colleagues and make passes at their dates. Even though, mired in alcoholism, he was no longer painting, he was still top dog among the abstract expressionists. An aspiring artist herself, Ruth (18 years his junior) was star-struck. She threw herself at him, and to no one’s surprise—except maybe Pollock’s—he caught her. After a steamy encounter in her apartment, they declared their mutual love, and the affair was off and running.

That summer Ruth wangled a job at the Abraham Rattner School of Art in Sag Harbor (the former Baptist church that now hosts Larry Rivers’ legs sculpture), handily close to Pollock’s home in Springs. No longer would their trysting require a Long Island Rail Road commute. Inevitably Pollock’s wife, Lee Krasner, noticed that something was up, especially when she caught the errant couple sneaking out of his studio the morning after. This led to the predictable ultimatum. To her credit, Ruth is frank about her doubts that the relationship had a future, although she had a habit of jumping back into the deep end in spite of her misgivings. When Lee took off for Europe, she moved into the Springs house, where she fantasized about reviving Pollock’s creativity and despaired over his black moods and violent temper.

It all builds to a climax on an August night, when a drunken driver, a misjudged curve and an overturned convertible spelled serious injury for Ruth and death for Pollock and another passenger. This section of the memoir is both cinematically vivid and melodramatic to the point of bathos, including a flashback to her rejection by a judgmental father. And by the time the book appeared in 1974, her pledge of enduring devotion: “That great romantic love. It can never come again,” was sounding a little hollow. Pollock’s body was barely cold when she took up with his great rival, Willem de Kooning, followed by a veritable Who’s Who of male art-world luminaries. Nevertheless, for the rest of her life—she died last March at the age of 80—Ruth dined out on Pollock, and I don’t mean the fish.