My “Eye On Art” column appears monthly in the Sag Harbor Express

“Eye On Art” has been suspended until further notice.

“Locally Sourced” at the Heckscher

2-27-20

The Heckscher Museum of Art in Huntington, overlooking the lake in a public park off Route 25A, was founded a hundred years ago by August Heckscher, a German-born industrialist and philanthropist whose grandson, August II, was the New York City Parks Commissioner in the Lindsay administration. The senior Heckscher established the park and museum that bear his name in 1920 as gifts to the people of Huntington, “especially the children.” Three of his grandchildren served as the models for Youth Eternal, a sculptural fountain by Evelyn Beatrice Longman, which he commissioned for the museum’s lobby.

The Heckscher’s wide-ranging collection includes European and American art spanning three centuries. To celebrate its centenary, the museum is focusing on works by regional artists, from Edward Moran’s atmospheric 1872 study of fog-bound sailboats in New York Bay (one of Heckscher’s original donations) to a pair of mixed-media works on paper from Bastienne Schmidt’s Underwater Topography series, completed last year. Comprising more than 100 works, “Locally Sourced: Collecting Long Island Artists,” on view through March 15, illustrates the diversity of the region’s creative community, with something to please everyone’s taste, including the children’s.

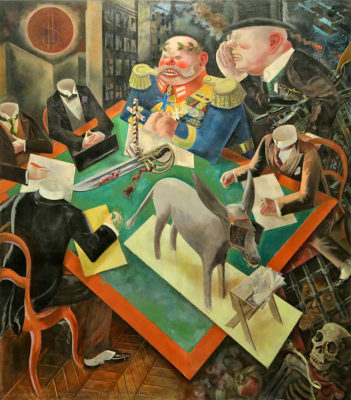

The highlight, however, is a painting with a decidedly adult theme: George Grosz’s 1926 masterpiece, Eclipse of the Sun, a mocking critique of the Weimar-era German government by one of the foremost Berlin Dadaists. The artist, who lived in Huntington in his later years and taught art at the museum, brought it with him when he fled the Nazis. After his death, the Heckscher bought it, in part with money raised by local children tossing coins into the Longman fountain. It is unquestionably the most important painting in any Long Island museum collection, but it’s not the only gem the Heckscher owns.

The exhibition is divided into four themes, and each has its share of outstanding works. “Artistic Exchanges” surveys the art colonists who made Long Island, especially the East End, a destination for successive generations, beginning with the Tile Club in the 1870s. Among them was William Merritt Chase, founder of the Shinnecock Summer School of Art, who is represented by a small but characteristic view of the sandy terrain near his Southampton studio. Landscapes by Thomas and Mary Nimmo Moran—whose East Hampton home, now a museum, is lovingly depicted by Theodore Wores—capture the bucolic surroundings that attracted them to the area, where they settled in 1884.

Among the works by the next wave of artistic transplants, abstract and representational alike, are fine examples by James Brooks, Elaine de Kooning, Jimmy Ernst, Ibram Lassaw, Alfonso Ossorio, Betty Parsons, Jackson Pollock, Fairfield Porter, Larry Rivers and Esteban Vicente, all of whom gravitated to the East End. In addition to Porter’s sensitive portraits of his wife and daughter, there’s a handsome bronze head of Porter himself by St. James native Robert White. Brooks and Lassaw are among the many others immortalized in Hans Namuth’s 1962 photograph, Artists on the Beach.

The area around the museum also boasts an exceptional complement of artists, as shown by the “Huntington’s Own” theme. In addition to Grosz, chief among them is the modernist master Arthur Dove, whose Centerport home belongs to the Heckscher. Together with his wife, the painter Helen Torr, Dove was drawn to the local scenery, on which he based what he called extractions, rather than abstractions. His 1941 watercolor, Untitled Centerport #2, for example, uses translucent strokes and simplified forms to evoke sails catching the wind and shimmering sunlight reflected on water.

Female artists are highlighted under the “Women’s Voices” theme, which includes noteworthy paintings by Torr, Parsons, de Kooning, Louise P. Sloane, Pat Ralph and Lisle Spilman, and sculpture by Elizabeth Strong-Cuevas and Esphyr Slobodkina, whose The Typewriter Bird amusingly re-configures the machine’s parts as bristly plumage. Hedda Sterne’s stylized take on an outboard motor and Miriam Schapiro’s three examples of the mixed-media work for which she coined the term femmage, are among the standouts here.

The most comprehensive theme is “Long Island Environments,” including farm fields, beaches, woodlands, backyard gardens and ponds. Scattered throughout the museum’s four galleries, paintings interpret the landscape in styles that run the gamut from the meticulous naturalism of Alfred Thompson Bricher’s shoreline scenes to Jane Wilson’s impressionistic canvas, Midsummer Midnight. Among the photographs, Neil Scholl’s panoramic view of Orient State Park contrasts with Stuart McCallum’s close-up, Beech Study #2, which zeroes in on the tree’s convolutions. As “Locally Sourced” demonstrates, artists of all persuasions continue to find inspiration here.

Turner in Mystic

1-30-20

When James Mallord William Turner died in 1851, he left the paintings that remained in his estate to Great Britain. The nation, however, was ill prepared to receive this magnificent legacy, numbering nearly 300 oil paintings and some 30,000 works on paper. Turner had intended for a special gallery to be built to display them, but they wound up moving from place to place until 1876, when they found a temporary home at the National Gallery in London. Finally, in 1910, the bulk of the bequest was transferred permanently to the Tate Gallery, now known simply as Tate, which opened a special wing for it in 1987. Ninety-three of Tate’s watercolors, together with four oils—said to be the largest selection of Turner’s work ever shown in the US—are on view through February 23 at Mystic Seaport Museum, across Long Island Sound in Connecticut, the exhibition’s only North American venue.

When James Mallord William Turner died in 1851, he left the paintings that remained in his estate to Great Britain. The nation, however, was ill prepared to receive this magnificent legacy, numbering nearly 300 oil paintings and some 30,000 works on paper. Turner had intended for a special gallery to be built to display them, but they wound up moving from place to place until 1876, when they found a temporary home at the National Gallery in London. Finally, in 1910, the bulk of the bequest was transferred permanently to the Tate Gallery, now known simply as Tate, which opened a special wing for it in 1987. Ninety-three of Tate’s watercolors, together with four oils—said to be the largest selection of Turner’s work ever shown in the US—are on view through February 23 at Mystic Seaport Museum, across Long Island Sound in Connecticut, the exhibition’s only North American venue.

Turner was a child prodigy; he entered the Royal Academy at age 14, and exhibited his first watercolor there the following year. He soon became known for his uncanny ability to capture atmospheric effects, which he experienced on his many travels in Britain and on the Continent. The Tate collection includes nearly 300 sketchbooks from those trips, many with color notations for reference in the studio, where he would work up the material into finished oils and watercolors. The earliest work in the show, View in the Avon Gorge, a watercolor painted when Turner was all of 16, illustrates his mastery of sophisticated composition, with the river bend in counterpoint to the swirling clouds, and subtle tonality, two of the qualities that would become hallmarks of his mature work. It also shows that he could render details convincingly if he wanted to, belying his critics’ contention that his work was slapdash.

Organized in seven thematic sections, the exhibition charts Turner’s forays into various subjects, including topography, architecture, narrative and marine. Even two of the diagrams for his Academy lectures on perspective are included. Three of the four oils are part of the section devoted to seascapes, Stormy Sea with Dolphins, ca. 1835-40, being especially evocative. But the bulk, and great delight, of the show is the watercolors, some quite large, like the early View of Fonthill Abbey, at 41 ½ x 30 inches, in which the distant structure is scarcely visible in the mist. Most are in the small to medium size range, with many intimate sketches, especially in the “Light and Colour” section, that dispense with details in favor of generalized studies of natural phenomena such as storms, sunsets, winds and waves. It’s no wonder that Turner is widely considered to be the progenitor of Impressionism.

From the crags of Mont Blanc to the lowlands of Holland and coastal England, Turner sought and found vistas that he translated into his own sublime vision of nature. They often include sketchily rendered buildings and sailing vessels, as well as animals and human figures, both for scale and to emphasize the drama of the elements and their influence on civilization. But though Turner loved a good shipwreck, it’s not all turbulence and peril. The waters can also be calm, as in his glowing sunset over Venice’s lagoon, a luminous study of Lake Geneva, and a view of Bamburgh Castle, on the Northumberland coast, which he evidently visited on a rare clement day.

Those who have seen the outstanding biopic, “Mr. Turner,” in which Timothy Spall portrays him in later life, will know that the artist was famous for his iconoclastic techniques, including spitting on the canvas, scraping his watercolors with his fingernails, and working into his paintings with his fingers. You can find that effect in the current exhibition’s Rain Falling Over the Sea Near Boulogne, an 1845 watercolor, in which the clouds are streaked in by hand. Even when using conventional brushwork, Turner’s touch is autographic and the strokes are clearly visible, which gives many of his works a sketchy, unfinished character that was not universally admired in his day. One fellow Academician described them as “blots.” Actually he did use blotting, but with transcendent results, hailed by later generations of representational and abstract artists alike and beloved by the general public.

“J.M.W. Turner: Watercolors from Tate,” an unprecedented opportunity to see for yourself why the artist is held in such high regard, is only a ferry-ride away. No doubt the artist would be pleased if you were to brave the crossing.