Three Cheers for MoMA

12-02-2010

It’s a perennial complaint that, no matter how big the Museum of Modern Art gets, it never has enough room to do justice to its permanent collection. This problem is hardly unique to MoMA—most of the well-stocked museums are in the same boat. So much space is occupied by temporary loan shows designed to draw crowds eager for novelty that most of the stuff they own languishes in storage. It takes an economic downturn to make them rummage around the vault for material that they don’t have to truck in and are already insuring. That’s just what MoMA did for “Abstract Expressionist New York,” a three-part extravaganza, on view through next April, which fills the museum’s fourth floor and spills over onto two other floors.

So how come everyone isn’t cheering? Delighted? Thanking MoMA for giving us a long-overdue look at treasures usually squirreled away, some of them never before out of the warehouse? Of course they always display a good selection of New York School paintings, sculpture and works on paper, but this is the first time they’ve devoted so much space to them, and explored the topic in such depth. Yet the critical response has ranged from tepid to downright hostile. It seems that MoMA can’t win for losing. Why is that?

The chief objection is that the show doesn’t challenge the orthodox view of Abstract Expressionism—America’s greatest contribution to world art—as a boy’s club dominated by a few superstars. In The New York Times, Roberta Smith hurled the first brickbat, calling its focus “myopic,” while The New Republic’s Jed Perl heaped it with scorn, labeling it “uninspired and predictable.” To Ariella Budick of The Financial Times, it “re-tells the same saga,” and in The Huffington Post Sharon Butler huffed that, in spite of the inclusion of some lesser-knowns, “the familiar easily outmuscled the newly anointed.”

None of these complaints take into consideration an important fact. An exhibition drawn entirely from a museum’s collection comprises, you guessed it, only what belongs to the museum, so there are bound to be gaps. Without loans, MoMA couldn’t show some New York artists who deserve to be included—for example, Kyle Morris, Wilfrid Zogbaum and Perle Fine—because the museum doesn’t own their work. And speaking of Perle Fine, she is indeed one of the deserving women who have often been left out or overlooked, but several of the other female New York School artists are present and well accounted for. There are excellent pieces by Hedda Sterne, Joan Mitchell, Louise Nevelson, Lee Krasner, Louise Bourgeois, Dorothy Dehner and Grace Hartigan, refuting the contention that women need not apply for membership in the Ab Ex club. True, as Sharon Butler noticed, the only Helen Frankenthaler painting on view is not the best of the several MoMA owns. But neither is Jack Tworkov well represented by his solitary painting, one of only two in the collection and not the better one. And alas, only four de Kooning paintings made the cut. His famous Woman I is front and center, but where is Woman II?

None of these complaints take into consideration an important fact. An exhibition drawn entirely from a museum’s collection comprises, you guessed it, only what belongs to the museum, so there are bound to be gaps. Without loans, MoMA couldn’t show some New York artists who deserve to be included—for example, Kyle Morris, Wilfrid Zogbaum and Perle Fine—because the museum doesn’t own their work. And speaking of Perle Fine, she is indeed one of the deserving women who have often been left out or overlooked, but several of the other female New York School artists are present and well accounted for. There are excellent pieces by Hedda Sterne, Joan Mitchell, Louise Nevelson, Lee Krasner, Louise Bourgeois, Dorothy Dehner and Grace Hartigan, refuting the contention that women need not apply for membership in the Ab Ex club. True, as Sharon Butler noticed, the only Helen Frankenthaler painting on view is not the best of the several MoMA owns. But neither is Jack Tworkov well represented by his solitary painting, one of only two in the collection and not the better one. And alas, only four de Kooning paintings made the cut. His famous Woman I is front and center, but where is Woman II?

Above: Installation view of “Abstract Expressionist New York: The Big Picture,” with Gaea, by Lee Krasner, at left and Willem de Kooning’s Woman I at right. Photo: Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Curatorial quibbles aside, another fact must be faced. While there were quite a few Ab Ex painters and sculptors active in New York in the movement’s heyday—the historian Irving Sandler estimates that some 200 artists would qualify for inclusion—there aren’t that many whose work has stood the test of time. A comprehensive survey would be as much of a mishmash as a group show in one of the period’s Tenth Street co-ops. Do we really want something like that at MoMA? I sure don’t.

I want to see the cream of the crop, and there’s cream aplenty in “Abstract Expressionist New York.” Paintings that invite you to dive in and swim around, others that dare you to get anywhere near them. Sculpture that looms majestically, barks and snaps like a junkyard dog, or seduces you with its sensual appeal. Drawings that show you what the artist was thinking. And so many of them! In spite of the gaps, the collection is huge. What a treat to see how, over the decades, curators and donors recognized the importance of Ab Ex and saw to it that the museum got its share, including many first-rate examples that are rarely seen. Ibram Lassaw’s spidery sculpture, Kwanon, James Brook’s Qualm, an outstanding stain painting, and dynamite canvases by Bradley Walker Tomlin, Richard Pousette-Dart, Alfred Leslie and Norman Lewis enlarge the canon without diluting its quality. Yes, the show is dominated by the so-called usual suspects, but what’s wrong with roomfuls of Pollocks, Klines, Newmans and Rothkos? As far as I’m concerned, the more the better, and more power to MoMA for giving this aspect of its collection such a splendid airing.

painting, and dynamite canvases by Bradley Walker Tomlin, Richard Pousette-Dart, Alfred Leslie and Norman Lewis enlarge the canon without diluting its quality. Yes, the show is dominated by the so-called usual suspects, but what’s wrong with roomfuls of Pollocks, Klines, Newmans and Rothkos? As far as I’m concerned, the more the better, and more power to MoMA for giving this aspect of its collection such a splendid airing.

Installation view of “Abstract Expressionist New York: The Big Picture,” paintings by Philip Guston, Hans Hofmann and Willem de Kooning. Photo: Jason Mandella, courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Jobs for Artists? Don’t Hold Your Breath

11-04-2010

Jobs, jobs, jobs—the three top issues in Tuesday’s Congressional elections. Will the 112th Congress do anything to lower the unemployment rate? Even if they do, it’s not likely to benefit artists. Heck, there’s already a federal jobs program for them on the books. So why aren’t artists all across the country cashing government paychecks right now? I’ll get to that.

In the years since the Great Depression, when the New Deal put artists on Uncle Sam’s payroll, what part has the federal government played in support for individual artists? A very small one. The National Endowment for the Arts, created under the Johnson administration, offered competitive grants, but they evaporated in the 1990s when the NEA became the demagogue’s delight—an easy target for budget-cutters whipping up outrage over controversial exhibitions. Like most federal agencies, the NEA relies on Congressional appropriations, and politicians are naturally sensitive to charges of spending your tax dollars on smut.

Fortunately there’s a way around Congress that allows the government to patronize contemporary artists. Under the longstanding percent-for-art clause in capital projects, the General Services Administration’s Arts in Architecture Program commissions works of art for new federal buildings. But the artists must conform to rigid standards and regulations that may well be at odds with creative expression. And commissions awarded at the federal level may not please the locals. Perhaps the most famous example is a 1981 GSA Arts in Architecture project, Tilted Arc, a 120-foot long, 12-foot tall Cor-Ten steel wall that loomed menacingly in front of the federal office building in downtown Manhattan. Richard Serra, the artist who designed it, was quoted as saying: “Art is not democratic. It is not for the people”—a sentiment with which the denizens of Federal Plaza clearly agreed. Many people who worked there hated the thing, and after a contentious process of hearings and appeals it was removed in 1989.

On the other hand, some communities have come to admire and embrace government-sponsored art that was initially greeted with skepticism or hostility. Both the NEA and the GSA have been responsible for public sculpture installations designed to bolster civic pride and signal that their host communities were “progressive”—that’s a code word for willing to accept modern abstract art.

On the other hand, some communities have come to admire and embrace government-sponsored art that was initially greeted with skepticism or hostility. Both the NEA and the GSA have been responsible for public sculpture installations designed to bolster civic pride and signal that their host communities were “progressive”—that’s a code word for willing to accept modern abstract art.

The NEA’s Art in Public Places Program began in 1969 with Alexander Calder’s La Grande Vitesse, a bright red, 43-foot tall stabile in Grand Rapids, Michigan, which had its share of vocal critics. Flamingo [right], an even larger scarlet stabile by Calder, was commissioned by the GSA and installed in Chicago’s Federal Plaza in 1974. At first the City of the Big Shoulders was perplexed by the queer bird that had landed in the Loop, but it wasn’t long before Chicagoans were won over by its whimsicality, and today both La Grande Vitesse and Flamingo are beloved civic landmarks.

The closest we’ve come to federal jobs for individual artists since the New Deal was the Comprehensive Employment and Training Act of 1973, which provided block grants for unemployment relief to state and local governments. Although it was phased out by the Reagan administration in 1982, the CETA project serves as a model for decentralized federal support for artists. While focusing on community service, it directly subsidized creative development by paying artists a living wage. It also reinforced the notion that they’re workers, not self-indulgent idlers or hobbists.

During the Obama campaign, there was talk of an Artists Corps, a public service project that would employ artists in educational and community settings—not in their own studios, but at least, like CETA, it would pay them to do work that benefits the community and makes use of their creative talents. What happened to that plan?

Politifact dot com reports that the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act, which President Obama signed into law in April 2009, authorizes federal funding for “skilled musicians and artists to . . . work in the public domain with citizens of all ages.” On that basis, Politifact rates the President’s campaign pledge as a promise kept. But so far only $277,000 has been spent on such a project—the Maryland Institute’s Community Art Corps—and the prospects for an appropriation from the 112th Congress look pretty dim. I think it would take another New Deal to get artists back on the job, and I’m not holding my breath for that.

Politifact dot com reports that the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act, which President Obama signed into law in April 2009, authorizes federal funding for “skilled musicians and artists to . . . work in the public domain with citizens of all ages.” On that basis, Politifact rates the President’s campaign pledge as a promise kept. But so far only $277,000 has been spent on such a project—the Maryland Institute’s Community Art Corps—and the prospects for an appropriation from the 112th Congress look pretty dim. I think it would take another New Deal to get artists back on the job, and I’m not holding my breath for that.

President Barack Obama signs H.R. 1388, the Edward M. Kennedy Serve America Act, at The SEED School of Washington, D.C., April 21, 2009. (Official White House Photo by Lawrence Jackson)

The Parrish: what have you got when it’s gone?

10-07-2010

The thump of Governor Paterson’s shovel breaking ground on July 19 for the new Parrish Art Museum in Water Mill must have sounded to the Southampton village elders like a wake-up call. The very next day, they announced the creation of an “arts district” in beautiful downtown Southampton, embracing the Cultural Center, the Rogers Memorial Library, Peconic Public Broadcasting, the Historical Museums and the Parrish, which is its anchor and raison d’etre. The district’s first annual fall festival, billed as its “coming-out party” and dubbed Arts Harvest Southampton, is now underway, and not a moment too soon. That line, “you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone,” from the old Joni Mitchell song, comes to mind. What happens to the arts district when its chief attraction leaves town?

As reported in July, the arts district is a key element of the village’s so-called vision plan, which recommends making art “a defining characteristic” of Southampton. So now the planners and officials are scrambling to figure out what to do with the building when the Parrish vacates it in 2012. They should have thought of that back in 1998, at the time of the museum’s centenary, when ambitious expansion plans were unveiled. That proposal, which called for an aggressively modern glass pavilion and demolition of part of the Job’s Lane garden wall, was met with hostility from several quarters, including the village board. No construction could be done without their approval, and not only because of zoning restrictions.

The village actually owns the Parrish’s building [left]. Originally called the Southampton Art Museum, it was deeded to the village in 1941 by Mrs. Samuel Longstreth Parrish, the widow of the museum’s founder. In short order the collections of art and antique furniture were relegated to the basement and the galleries were used to store plumbing fixtures (the mayor at the time was a plumber). When it was learned that the next step was to demolish the building and replace it with a parking lot—shades of Joni Mitchell again—a group of concerned citizens formed a private non-profit board of trustees and revitalized the museum, which had been renamed in Parrish’s honor, in 1952.

The village actually owns the Parrish’s building [left]. Originally called the Southampton Art Museum, it was deeded to the village in 1941 by Mrs. Samuel Longstreth Parrish, the widow of the museum’s founder. In short order the collections of art and antique furniture were relegated to the basement and the galleries were used to store plumbing fixtures (the mayor at the time was a plumber). When it was learned that the next step was to demolish the building and replace it with a parking lot—shades of Joni Mitchell again—a group of concerned citizens formed a private non-profit board of trustees and revitalized the museum, which had been renamed in Parrish’s honor, in 1952.

But although the collections, governance and funding are private, the trustees can’t touch the building without the village’s say-so, and that wasn’t forthcoming. Hence the decision to move, first to the Southampton College campus, and when that fell through, to the Water Mill location.

On a smaller scale, this echoes the struggle to relocate the Barnes Foundation from its original home in Merion, Pennsylvania to Fairmont Park in Philadelphia, although in the opposite direction—from in town to the outskirts, whereas the Barnes will move from the suburbs to downtown. If you’ve seen the film, “The Art of the Steal,” you know that this plan has caused a titanic controversy, fueled in part by charges of mismanagement that bear no resemblance to the Parrish’s situation. But what strikes me as similar is the turnaround of the good people of Merion. For decades they wished the place would disappear, prevented it from expanding, and resented its parking problems, litterbug visitors and annoying tour bus traffic. Now that it’s leaving, however, they’re wringing their hands, howling in protest and passing resolutions demanding that it stay. Too little, and way too late.

Like Merion, Southampton is soon going to have a big, beautiful but very vacant building in the heart of town—not exactly a tourist attraction. Mayor Mark Epley has acknowledged that the Parrish’s departure will “leave a hole for a long time,” unless some alternative is found, preferably one that’s compatible with the arts-district concept. One proposal is to make it a multi-use facility for visual and performing arts, a kind of village cultural center. Oops, wait a minute, isn’t there already one of those just down the block? Let’s think again.

Remember the Long Island Automotive Museum that used to be on the highway, next door to the tombstone shop? That was so cool. Why not revive it, and put it into the Parrish building? I think it could work. They had an Avanti in the transept gallery not long ago, and it looked pretty good in there. Roll in a few dream boats and cream puffs for visitors to drool over, show car-chase movies in the concert hall, and problem solved. Not a good fit for the arts district? Anyone who thinks cars can’t be works of art didn’t see that Avanti.

Let’s See Your Legs, Larry

08-26-2010

The oversize legs striding along Henry Street have prompted some spirited debate in these pages. Clad only in old-fashioned nylons (sans garter belt), they add a dash of spice to the village’s architectural streetscape. Passers-by, not knowing the backstory, may well wonder where they came from and how they got here. Surely they didn’t walk to Sag Harbor on their own.

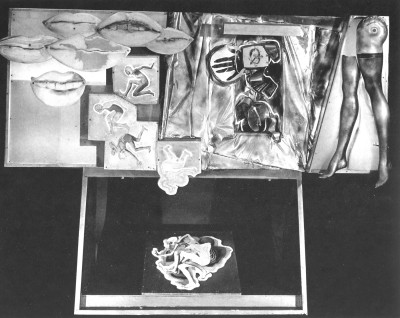

Their journey began in Lake Grove, Long Island, home of the Smith Haven Mall. When it opened in 1969 it was one of the nation’s largest shopping complexes, according to The New York Times, which also reported that it contained an unprecedented mixture of “high art and low commerce,” thanks to commissions arranged by Leonard Holzer, an executive with the mall’s developer. As it happened, Holzer’s wife, Jane, was something of an art-world personality. An uptown girl with downtown inclinations, Baby Jane, as she was known, was one of Andy Warhol’s “superstars,” appearing in several of his films, including Soap Opera, Batman Dracula and Ciao Manhattan. She persuaded her husband that the mall should feature site-specific work by contemporary artists, and got him to earmark $350,000 for the project. Among the pieces she convinced Holzer to commission—oddly, none by Warhol—were a stabile with a mobile top by Alexander Calder (dubbed Janey Waney in her honor) and a mural by Larry Rivers, 40 feet long and 15 feet tall, titled Forty Feet of Fashion [above].

Their journey began in Lake Grove, Long Island, home of the Smith Haven Mall. When it opened in 1969 it was one of the nation’s largest shopping complexes, according to The New York Times, which also reported that it contained an unprecedented mixture of “high art and low commerce,” thanks to commissions arranged by Leonard Holzer, an executive with the mall’s developer. As it happened, Holzer’s wife, Jane, was something of an art-world personality. An uptown girl with downtown inclinations, Baby Jane, as she was known, was one of Andy Warhol’s “superstars,” appearing in several of his films, including Soap Opera, Batman Dracula and Ciao Manhattan. She persuaded her husband that the mall should feature site-specific work by contemporary artists, and got him to earmark $350,000 for the project. Among the pieces she convinced Holzer to commission—oddly, none by Warhol—were a stabile with a mobile top by Alexander Calder (dubbed Janey Waney in her honor) and a mural by Larry Rivers, 40 feet long and 15 feet tall, titled Forty Feet of Fashion [above].

Heavily into his assemblage phase at the time, and influenced by his friendship with the Swiss kinetic sculptor Jean Tinguely, Rivers delighted in using vinyl, Plexiglas and recycled material to make dimensional mixed-media constructions, sometimes with moving parts. His recently completed The History of the Russian Revolution, for example, featured storm windows, plumbing pipes and real military weapons. Like Warhol and the other Pop artists, Rivers embraced the iconography of mass-market culture. His concept for the mall included references to some of the consumer products available in the surrounding shops: cosmetics (floating lips, à la Man Ray), bathing suits (somersaulting swimmers), appliances (including a clock with Leonard Holzer’s portrait as the face) and hosiery, represented by a pair of disembodied mannequin legs modeling sexy black stockings. There was also an automatic slide show, which broke down not long after the mural was installed. It was never repaired.

That was only the first step in the gradual deterioration of the mall and its art. The Calder lost its moving top section, and the base was insensitively relocated outside, where it graced the parking lot. Other pieces simply disappeared. Forty Feet of Fashion remained in place until another developer took over the mall in 1985 and did a major renovation. Rivers’ mural didn’t gibe with the new look, themed around the restored Calder, so the developer suggested donating it to a museum. But Rivers insisted on its restoration first. When they couldn’t come to terms, the mural was disassembled. Rivers got a few of the elements, including one of the swimmers, which is on view through August 31 at the Vered Gallery in East Hampton, as part of the exhibition, “Larry Rivers: Pop Icons.” He also got the legs, slightly reworked and repainted them, and planted them on the lawn outside his house on Little Plains Road in Southampton, where they disquieted the neighbors until his death in 2002. He later made a duplicate set, which gallery owner Ruth Vered and her partner Janet Lehr acquired and installed on their Sag Harbor property, the former Bethel Baptist Church, two years ago.

Opinion seems to be divided on their appropriateness, and not only because they’re out of character with their surroundings. As the work of an artist whose controversial video portrait of his daughters’ sexual development is the subject of a tug of war between his younger daughter Emma and his estate, they are viewed less than sympathetically by those who see the artist as a degenerate who exploited his children in pursuit of his own agenda. That argument will be settled by the interested parties, and really has no bearing on the merits of the legs as a work of public art in a prominent village location.

Considering the paradoxical dearth of public art in a village notable for the many artist who live and work here, I think it’s about time we got a monument by a prominent local artist that’s livelier and more noteworthy than the generic Civil War statue at the intersection of Main and Madison. Rivers was a member of the East End art community for more than half a century. To be sure, he didn’t live in Sag Harbor, but he is buried in our Jewish cemetery, so he’s truly a permanent resident. The former church is also a fitting location for his sculpture. It became an art center when Abraham and Esther Rattner bought it in the 1950s—it’s where Jackson Pollock’s girlfriend, Ruth Kligman, worked briefly during the summer of 1956—so what could be a more suitable spot for showing off Larry’s shapely legs?

Artists Don’t Get No Respect

07-29-2010

Artists need to get over themselves. That was the blunt message from Jerry Saltz, New York magazine’s senior art critic, to his artist-dominated audience at Guild Hall on July 18th, when he delivered the Annual Pollock-Krasner Lecture. Funny, irreverent, self-deprecating and voluble, Jerry is the art world’s answer to Rodney Dangerfield. His monologue, provocatively titled “The Good, The Bad and the Very Bad: An art critic talks about art, demons, and other things that have to do with making art today,” focused on how artists’ expectations often outstrip achievement. And he was just as frank about unrealistic notions of the critic’s power and influence as he was about the artist’s misguided visions of fame and fortune.

Having been a journalistic art critic for more than 30 years, first for The New York Times’ now-defunct Long Island section and then for WLIU radio, I was delighted to hear Jerry discredit the image of the critic as a tastemaker whose judgments can make or break an artist’s career. On the contrary, he maintained, critics play a limited role in the rise and fall of artists’ reputations, and virtually none in determining the market for their work. It’s only natural to want a rave review, but I agree with Jerry’s contention that it has very little influence on an artist’s ultimate success.

“Artists want everyone to love them,” Jerry declared. That’s an overstatement for effect, but it does highlight some of the demons that haunt the studio, where the artist labors in isolation and struggles to give tangible form to intangible concepts or feelings. Having the idea is one thing, finding a way to express it so others can get the message is something else again. Remember Edison’s assertion that genius is ten percent inspiration and ninety percent perspiration? Well, it may be a cliché, but it’s true. Then, having expended all that energy on an artistic labor of love, the demon of self-doubt pokes you with its pitchfork. Is my work good enough? Will anyone else get it? Then another demon takes a stab. What if no gallery will show it? Suppose it does get shown, but no one buys it? And even worse, what if it gets a bad review?

“Artists want everyone to love them,” Jerry declared. That’s an overstatement for effect, but it does highlight some of the demons that haunt the studio, where the artist labors in isolation and struggles to give tangible form to intangible concepts or feelings. Having the idea is one thing, finding a way to express it so others can get the message is something else again. Remember Edison’s assertion that genius is ten percent inspiration and ninety percent perspiration? Well, it may be a cliché, but it’s true. Then, having expended all that energy on an artistic labor of love, the demon of self-doubt pokes you with its pitchfork. Is my work good enough? Will anyone else get it? Then another demon takes a stab. What if no gallery will show it? Suppose it does get shown, but no one buys it? And even worse, what if it gets a bad review?

As far as Jerry is concerned, that should be the least of an artist’s worries, and I concur. Andy Warhol, the world’s most famous and successful modern artist, never got a favorable review in his life. Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, Julian Schnabel and other contemporary art stars do have their critical champions, but they’re regularly pilloried by others. What makes the market, according to Jerry, is marketing.

Before he spoke, Jerry mentioned to me that a poll by Art Review magazine had named him the fifty-fifth most important person in the art world—hardly a top draft pick. When I introduced him I included that statistic, which got a hearty laugh from the audience. Who was number one, they wanted to know. The answer: the art dealer Larry Gagosian. If what you want is commercial success, Jerry told them, find a dealer who will promote your work, an enthusiast to write about it and a few collectors who will invest in it, and don’t worry about whether critics or the general public love you or what you do.

If you think that sounds cynical, Jerry would be the first to agree with you. He has a pretty jaundiced view of the high-powered contemporary art scene. But even as he admonished artists to stop complaining that they don’t get enough recognition and to scale back their expectations of stardom, he encouraged them to remain true to themselves and to follow their inner necessity. Far from suggesting that they compromise themselves or just give up, he advised them to stay with it and keep it authentic. That’s the only way to be credible, and it holds true for art criticism as well. Both processes, he believes, should be intuitive, not calculated or formulaic, or they become mannered, shallow and pretentious.

In the end, credibility is the defining factor that both artists and critics need to embrace. Although they speak different languages—as Jerry put it, critics are dog-like in their direct communication with their audience, while artists are like cats, which express themselves indirectly—if they aren’t honest, they aren’t worth paying attention to. Authenticity, he insisted, is the true measure of success.

Art’s a Bargain

07-01-2010

I don’t know about you, but with the economy the way it is, I’m on the lookout for bargains. More than ever, we want value for our money, and when it comes to great deals we can’t do better than our museums or historic sites. They’re popular destinations for locals and out-of-towners alike, but not everyone realizes what bargains they are.

These places are called non-profits for a reason. There’s a huge gap between what you pay at the door and what it actually costs to let you in.

At the museum where I work, the increasing number of requests for discounts prompted me to calculate that differential, and to ask some of my colleagues to do the same. The results of my informal survey bear out my contention that cultural attractions are among the best buys in town.

My museum—the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center in Springs, where the artists Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner lived and worked—belongs to Stony Brook University’s non-profit foundation. It has beautiful grounds overlooking Accabonac Creek and a charming 19th century house full of their stuff, but the main draw is Pollock’s studio floor, covered with colorful remnants of his controversial paint-pouring technique. We’re open three days a week from May through October, and last year we had about 6,500 visitors.

We charge $5 for general admission and $10 for a one-hour guided tour. Members get in for free, and so do children under 12, as well as New York state and city university students, faculty and staff. When everything is factored in—salaries and benefits, utilities, insurance, supplies, advertising, and all the other expenses—each pair of feet on the floor in 2009 cost us $48.84. Admissions amounted to a little over $51,000, which averages out to $7.84 a person. So where did we get the other forty-one bucks?

Like most cultural organizations, we rely on several sources of income to make up the difference. We have no endowment, but our two staff positions are state-funded. The rest comes from memberships, museum store sales and other earnings, government and foundation grants, individual donations and fundraising events—the traditional non-profit strategy.

Zach Studenroth, director of the Sag Harbor Whaling and Historical Museum, which is also open seasonally, says that’s his formula too. Last year he had about the same number of visitors as we did. They paid $5 each, with discounts for seniors, students and groups, but the real cost of admission was $28. Your ticket gets you into one of the village’s grandest architectural confections, and once inside you see fascinating art and artifacts from Sag Harbor’s glory days as a whaling port. It’s an eccentric, eclectic and authentic tribute to a bygone era, all for about one-sixth of its actual value.

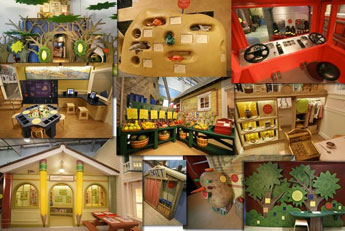

In Bridgehampton, the Children’s Museum of the East End [right] charges $9 for admission to a wonderland of interactive educational exhibits, where youngsters and grownups can have fun while they learn about the local community. The array of imaginative programming is staggering. There are classes, workshops, performances and special events, which help with the bottom line. They have the lowest differential among the five museums in the survey, but there’s still an $11 gap between the admission price and the $20 cost per capita. The executive director, Steve Long, tells me that they get a third of their money from earned income, a third from grants and gifts, and a third from fundraising activities. That’s a good balance, in line with what most unendowed non-profits aim for.

In Bridgehampton, the Children’s Museum of the East End [right] charges $9 for admission to a wonderland of interactive educational exhibits, where youngsters and grownups can have fun while they learn about the local community. The array of imaginative programming is staggering. There are classes, workshops, performances and special events, which help with the bottom line. They have the lowest differential among the five museums in the survey, but there’s still an $11 gap between the admission price and the $20 cost per capita. The executive director, Steve Long, tells me that they get a third of their money from earned income, a third from grants and gifts, and a third from fundraising activities. That’s a good balance, in line with what most unendowed non-profits aim for.

At the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton, a small endowment helps underwrite curatorial positions, but the bulk of the budget must be raised annually. The museum, which had about 26,500 visitors last year, boasts a fine permanent collection of 19th and 20th century American art and runs a lively year-round program of temporary exhibitions, lectures, films, concerts and classes. This is one of the biggest bargains on the South Fork. You pay $5 to get in—only $3 if you’re a student or senior, and free if you’re 18 or under—but if you paid what it costs you’d pony up a whopping $106. Admissions cover only about 1% of their general operating expenses.

Similar numbers are reported by East Hampton’s cultural center, Guild Hall, with the John Drew Theater and an art museum devoted to artists of the region, past and present, under the same roof. The museum asks only for a suggested donation, which makes a negligible contribution to the bottom line. Calculating its per capita cost is problematic, since the galleries are often open before performances and during intermissions, when audience members can see the exhibitions at no extra charge. Taken as a whole, each of the roughly 39,000 bodies that entered the building last year cost $88.71.

Why do museums routinely subsidize admissions so heavily? Because we can, thanks to those alternative sources of income. Also because we believe it’s the right way to serve our community. Guild Hall’s executive director, Ruth Appelhof, sums it up succinctly. “Our mission,” she says, “is about supporting the arts and artists on the East End, and inviting and providing access for all is paramount.”