My “Eye On Art” column appears monthly in the Sag Harbor Express

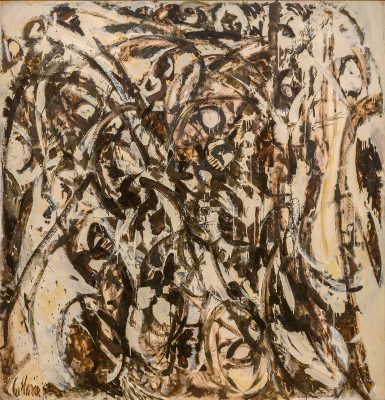

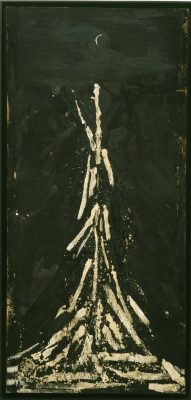

Lee Krasner’s Night Journeys

12-21-17

As a pioneering abstract expressionist, Lee Krasner relied on emotion and intuition to fuel her creativity. In her mature work, her subjective imagery offers many keys to the artist’s inner life. “My painting is so biographical,” she once told an interviewer, “if anyone can take the trouble to read it.” For example, following the tragic death of her husband, Jackson Pollock, in August 1956, she expressed her deep sorrow and conflicted feelings in three turbulent canvases, full of tearful eyes and contorted bodies.

By the following year, however, she had purged the negative energy that fueled those images and began a group of bright, upbeat paintings known as her Earth Green series. Their life-affirming exuberance was startling to those close to her, who knew that she was still in mourning. One friend described the series as an antidote to her grief. It could also be seen as a demonstration of her new-found independence, both personal and artistic, after years of devotion to Pollock’s career at the expense of her own. But if the 1957 Earth Green paintings appeared to herald a sustained positive trajectory for Krasner’s art, it was not to be. Her next series re-entered the somber emotional territory she had explored soon after Pollock’s death. Known as the Umber Paintings, it comprises some two dozen canvases from 1959-62, when she went, as she put it, “down deep into something that wasn’t easy or pleasant.” Five of them are on view through January 13 at the Paul Kasmin Gallery in Chelsea.

Krasner called the series her “night journeys” because they were in fact painted at night, but also because they are emotionally dark. Some were done in a New York City studio, others in the converted barn in Springs that had been Pollock’s studio. Her Earth Green series, painted in the barn, had already exorcised his spirit from that space, but she had a new loss to deal with: the death of her mother. This, compounded by her lingering grief and anger over Pollock’s death, precipitated a period of insomnia during which she painted at night under artificial lights. In the barn studio, she relied on the fluorescents that were installed in 1953. Since artificial lights have a distorting effect on colors, she decided to limit her palette to a deep, rich brown, occasionally supplemented by creamy white. Why brown? Why not midnight blue or black? A friend speculated that her choice was inspired by her chocolate-colored standard poodle, Ahab, which was always in the studio, keeping her company while she worked.

Dynamic and intense, rendered in sweeping, energetic strokes, the Umber Paintings are both lyrical and foreboding. This ambiguity enhances their visual fascination. Even without knowing the backstory, one senses that their roiling forms and pulsating rhythms represent strong emotions, some positive, some negative, playing off against one another. You can read in all kinds of psychological overtones, as indeed Krasner herself encouraged when she recommended biographical interpretations. In Uncaged, a thickly painted 1960 canvas in the current show, she reprises the same implosive, congested, weeping forms in her 1956 trio of post-Pollock mourning pictures, minus the vivid colors. Perhaps she considered those paintings effective vehicles for liberating her feelings and wanted to try a similar strategy to cope with this new round of sorrow.

Of the 1961 canvas titled Assault on the Solar Plexus, also on view at Kasmin, Krasner once remarked that it was “embarrassingly realistic.” Not that it actually depicts a body blow, since there’s no explicit human figure—though, as in most of her works from this period, there are veiled anatomical references. But it appears she attacked the center of the canvas with a stabbing motion of the brush, leaving thick, wound-like clots of umber paint. Evidently there was some violent, visceral sensation inside her that had to manifest itself in her art.

These are large, ambitious paintings. There’s nothing timid or tentative about them. Whether you believe they represent the artist’s inner conflicts or her way of resolving the emotional turmoil of those transitional years, they show Krasner literally flexing her muscles, extending her reach, and letting loose a lot of pent-up energy. By zeroing in on this crucial phase of her development, the exhibition offers an exhilarating demonstration of how she brilliantly exploited abstract art’s revelatory potential.

Partners in Design

11-23-17

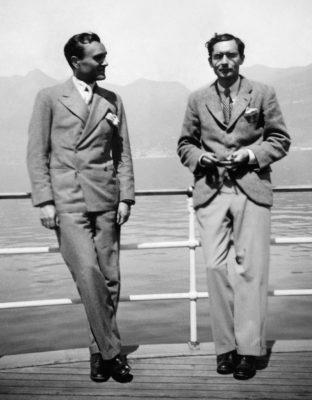

When he first visited the Bauhaus in 1927, Alfred H. Barr, Jr. was a 25-year-old art history lecturer at Wellesley College. He was deeply impressed by the German school’s emphasis on the interrelationship among various aspects of the fine and applied arts, as well as its innovative architecture and industrial design curricula. As he later wrote, the Bauhaus philosophy was in marked contrast to the retrograde American approach, in which modern art courses ended with “hostile remarks about van Gogh and Matisse,” and architecture students produced “elaborate projects for Colonial gymnasiums and Romanesque skyscrapers.” He would soon be in a position to remedy that situation.

Two years later, when Barr became the founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, his enthusiasm for all things Bauhaus was reinforced by his friendship with fellow Harvard alumnus Philip Johnson, whom he had met while teaching at Wellesley. They were among the organizers of “Bauhaus: Weimar, 1919–23 / Dessau, 1924,” presented by the Harvard Society for Contemporary Art in 1930-31, the first such exhibition in the United States. This initial project led to a long-term professional collaboration that exerted enormous influence on 20th century architecture and design in America. Early in his tenure at MoMA, Barr hired Johnson—who in those days had no architectural training but made up for that deficiency with boundless energy and resources—as the museum’s curator of architecture. Their shared taste for unadorned industrial-style design fundamentally shaped MoMA’s direction, as reflected in “Partners in Design,” on view through December 9 at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery.

Organized by the Liliane and David M. Stewart Program for Modern Design, Montreal, and the Montreal Museum of Art, which owns the Barr collection of 1930s tubular furniture, the show illustrates the ways in which MoMA’s in-house exhibitions, traveling shows and publications promoted Bauhaus-inspired functionalism. Installation photographs document the museum’s 1932 “Modern Architecture: International Exhibition,” a trend-setting survey, organized by Johnson, of what came to be known as International Style buildings. Two years later, Johnson’s “Machine Art” exhibition featured objects like a ship’s propeller, ball bearings, kitchen utensils and other utilitarian items in a fine-art context. The current show includes several examples, such as the Wear-Ever tea kettle, coffee pot and cake pans, that have never gone out of style and can be found in many kitchens today.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933 the Bauhaus was forced to close and several of its prominent faculty members, including Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius, sought refuge in the U.S. MoMA continued to champion their concepts, based on an integrated approach to contemporary design expressed in functional forms and truth to materials. In 1942 another exhibition, “Useful Objects in Wartime Under $10,” promoted Russel Wright’s American Modern tableware, Paul V. Gardner’s Pyrex cookware, and Peter Schlumbohm’s Chemex coffeemaker as inexpensive, practical examples of good design for the average home.

Speaking of home, the exhibition’s heart and soul is the original material from the Johnson and Barr apartments. These two men practiced what they preached. Johnson, who had family money, commissioned Mies to design his interiors. The décor included a Barcelona chair, a handsome custom-made rosewood low chest, and a day bed with a quilt by Mies’s partner, Lilly Reich. A light box shows stereoscopic views of the rooms, but the furniture speaks more eloquently for itself. So, too, does the less pricey material from the estate of Alfred and Marga Barr—steel and lacquer pieces designed by Donald Deskey and mass produced for the American market by the Ypsilanti furniture company. An armchair designed by Johnson, a clear homage to Breuer, was also in the Barr apartment, as was Breuer’s own B22 étagère. The ensemble is enhanced by abstract paintings by Fritz Glarner, Jean Xceron and László Moholy-Nagy from the Grey’s collection.

The exhibition concludes with a section, “Spreading the Gospel,” that traces the Bauhaus-inspired aesthetic into the postwar years, with textiles, tableware and furnishings by the likes of Eva Zeisel, George Nelson, Isamu Noguchi and Charles and Ray Eames. Some of these designs, like Nelson’s 1947 “Ball” wall clock and Noguchi’s Model 9 table lamp, are still in production, proving that the seeds sown 87 years ago by the Barr-Johnson partnership continue to bear fruit.

World War I Artists in Old Lyme

10-26-17

Among the many centennial commemorations of America’s participation in the First World War is a fascinating exhibition, “World War I and the Lyme Art Colony,” on view through January 28 at the Florence Griswold Museum in Old Lyme, Connecticut. Whether “over there” or on the home front, the artists’ contributions reflect in microcosm the ways in which the nation as a whole dealt with the conflict. Maybe it was a bit more personal for Old Lyme, since President Woodrow Wilson’s first wife, Ellen Axson Wilson, spent many summers painting there with her fellow American Impressionists until her death on August 6, 1914, five days after the declaration of war in Europe.

Even before the United States entered the fray in April 1917, Americans were providing humanitarian aid to the combatants. Artists made posters encouraging such philanthropy, but once we were in the war they became even more actively involved. Some of those who were too old for military service, including Old Lyme colonists Edmund Greacen, George Hand Wright and Guy Wiggins, went overseas to work for the Red Cross or other agencies aiding American soldiers. As a result of his experiences, Wiggins, who took supplies to the front lines, came home suffering from what was then called shell shock. Greacen was also deeply affected by his experiences in the combat zone. No stranger to France, he had lived and worked in Giverny before the war. His series of small oils on board are on-the-spot studies showing the ruins of French towns and monuments. They capture the poignancy he felt as he witnessed the desolation caused by artillery fire.

President Wilson had campaigned on the promise to keep us out of the conflict, and many Americans thought it was Europe’s problem, so it was important, not to say vital, to appeal to the public for support. Propaganda efforts were extensive, and artists did their part. Wright was one of eight commissioned to travel overseas to paint and draw troop-rallying images. While he never actually went to the front, Wright contributed scenes of combat, as well as sketches of recruits, to illustrate articles about the military. Although a draft had been enacted, Wright’s poster, “Enlist in the Navy,” is one of many made by artists—the most famous is James Montgomery Flagg’s finger-pointing Uncle Sam—to encourage volunteering for service. Posters also advocated the purchase of Liberty Bonds and other civilian contributions to the war effort.

Beyond active duty age, Everett L. Warner enlisted in the Naval Reserves, for which he created dazzle-pattern camouflage for commercial and naval ships. The show includes some of his designs, which look more like eye-catching cubist abstractions than eye-fooling disguises, but apparently they were quite effective in confusing the U-boats. They’re also quite a departure from his pre-war impressionist style, to which he returned when the war ended. While waiting for his discharge, Warner made landscape paintings from a Navy dirigible. The selection in the show illustrates the panoramic perspective afforded by observation from the air. According to the informative label, he was one of the first artists to sketch and paint aerial views.

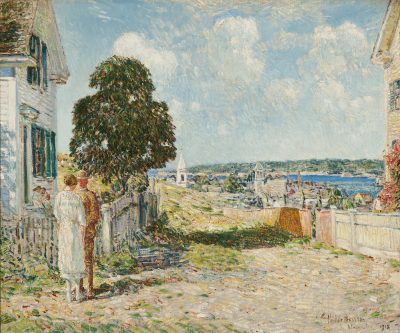

Two artists associated with Old Lyme also had East Hampton connections. Before he bought a home on Egypt Lane in 1919, Childe Hassam was a frequent visitor to the boarding house that’s now the Florence Griswold Museum. After being refused permission to serve as a military artist, he painted a now-famous series of scenes of flags on Fifth Avenue designed to arouse patriotic pro-war sentiment. Unfortunately none of them were available for this exhibition, which does include a Hassam lithograph, “Avenue of the Allies,” showing flags on display during a 1918 war-bond drive. His painting, To the 101st (Massachusetts) Infantry, also from 1918, depicts his nephew Roswell, a PFC in the regiment, preparing to leave for Europe. Set in the quaint New England port of Gloucester, it shows the soldier saying goodbye to a woman wearing a Red Cross nurse’s uniform. As the exhibition demonstrates, the role of women in the war contributed to the success of the suffrage movement, culminating in the passage of the 19th Amendment.

Everitt Herter, a son of the painter Albert Herter, whose East Hampton home was The Creeks, served as a camoufleur and was killed in action in France. To commemorate his son and other fallen soldiers, Herter painted a huge pastel, Spirit of the Doughboy, that hangs in Old Lyme’s Memorial Town Hall, dedicated in 1921 as a monument to the town’s veterans and casualties of World War I.

Calder’s Serious Fun

9-28-17

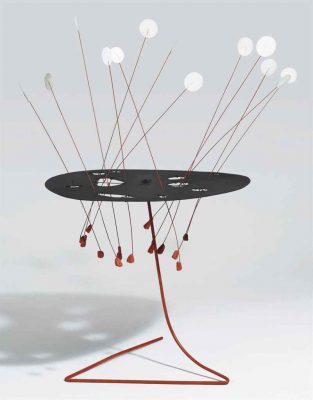

In 1948 the photographer and filmmaker Herbert Matter began work on a film about his friend, the sculptor Alexander Calder. Background footage was shot on the beach in East Hampton, where the Matter family was spending the summer. Images of waves washing on shore, undulating jellyfish, windblown leaves, grass and milkweed depict movement in nature, as observed by Matter’s son, six-year-old Alex, who was named after the artist. The scene then shifts to a “house full of things that moved,” actually Calder’s studio in Roxbury, Connecticut. There we see him at work on mobiles of all shapes and sizes, including some that are in the current exhibition, “Calder: Hypermobility,” at the Whitney Museum through October 23.

The Lipman Family Foundation; long-term loan to the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

Made under the auspices of the Museum of Modern Art, with a superb musical score by John Cage, the 19 1/2 minute film was released in 1950. Watching it on YouTube, I recognized the wire and sheet metal Aluminum Leaves, Red Post, Snake and the Cross, and Blizzard (Roxbury Flurry), now on view at the Whitney. They are among the mobiles that sway, shimmer and dance in space as Calder and Alex (nicknamed Pundy) set them in motion in the studio. At the museum, however, the rule is look but don’t touch. Even blowing on one—guilty, your honor—earns a sharp rebuke from the guard.

Yet movement, whether mechanical or induced by air currents, is the art’s raison d’etre, so the show is a bit frustrating. Apart from a couple of hanging mobiles that move ever so slightly in the ambient ventilation, the installation is static. To compensate, the pieces are activated on a posted schedule, with the unfortunate result that the relatively small gallery gets mobbed when one is about to go. I suppose I shouldn’t complain, since several of those with antique motors that haven’t worked in many years have been restored for this occasion. They twirl and bob and weave—you can see a few in action on the exhibition Web site.

With 36 pieces, the selection ranges across decades and media, offering a rare look at the variety of Calder’s experiments with animation. In addition to iconic examples of suspended mobiles, such as Big Red and Hanging Spider from the Whitney’s collection—the largest public holding of his work—there are key loans from the Calder Foundation, including most of the motorized pieces, some of them very subtle. S and Star, for example, is just a piece of plywood with a rotating cutout star and a wire that curls into an S shape. Seemingly simple, but mesmerizing.

There are also several classics among the floor-mounted mobiles, including Parasite, with its long tendril reaching out as if to attach itself to a host, Black Tulip, festooned with colorful blossoms, and The Water Lily, floating daintily up from its root. I was especially taken with Aspen, a small forest of quaking disks suspended in a perforated piece of sheet metal. It both rotates and sways, evoking the movement of its namesake trees in the wind. Even a couple of Calder’s little-known pivoting bronzes are here, and though they’re not among my favorites they show yet another aspect of his unorthodox use of materials. His father, the figurative sculptor Alexander Stirling Calder, was known for his monumental bronze statuary, but the son has given the medium a whole new twist—pun intended.

If one needed reminding of Calder’s amazing inventiveness, his seemingly inexhaustible repertoire of forms, and his uncanny ability to balance and animate them, the evidence is here. He’s also singular in his popularity. Perhaps no other abstract artist is as admired by the art world and general public alike. It was Marcel Duchamp, his fellow iconoclast, who coined the term mobile to describe Calder’s unique contribution to modern sculpture. One of a handful of Americans embraced by the avant-garde in Paris long before American art was taken seriously in Europe, he managed to create works that are both charming and challenging, simultaneously playful and provocative. In the Matter film, you can see the delight on young Alex’s face as he sets them in motion, and the sense of wonder transcends all other distinctions. You’ll see similar expressions on the faces of visitors to the Whitney exhibition.

Florine Stettheimer, Visual Poet

8-31-17

In a poem at the entrance to “Florine Stettheimer: Painting Poetry,” on view through September 24 at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan, the artist expresses her adoration for “all tinsel creation,” shopping, and other fripperies, mentioning her own paintings on the same level as “Walt Disney cartoons / and colored balloons.” This attitude, together with her position of privilege and the faux naïve painting style she affected, has placed her work in a kind of art-historical limbo. On the one hand it’s seen as a charming but lightweight oeuvre that’s easy to dismiss as amateur dabbling. At the other extreme she’s periodically hailed as a pioneer of the 20th century avant-garde—right up there, as one recent critic claims, with Chagall, Miró and Malevich.

Do I buy that? In a word, no. But neither do I side with those who write her off as a dilettante. As the current show demonstrates, Stettheimer was a serious, multi-talented artist with an ambitious agenda that is nicely spelled out in the documentation. That her ambitions were often thwarted didn’t deter her from pursuing them.

One of four daughters of a wealthy Jewish banker, Stettheimer grew up in a prosperous, cultured environment and studied art in Paris, Rome and Munich as well as New York City. Examples of her student work illustrate her technical skill, and several early portraits show that she could paint naturalistically. So it was clearly a deliberate decision on her part to develop a more modern approach, one influenced by Symbolism and Surrealism as well as a burgeoning interest in American folk art that also inspired several of her contemporaries.

After years living abroad, at the outbreak of World War I the Stettheimer family returned home and established a New York salon, where the three unmarried sisters, Florine, Carrie, and Ettie, hosted gatherings of the city’s artistic elite. Florine’s circle included Georgia O’Keeffe, Carl Van Vechten, and Marcel Duchamp, who championed her work. She focused on a hermetic social world in which stylized figures bordering on caricature are rendered in confectionary colors. Attenuated bodies with tapering limbs pose languidly or cavort in settings that reflect her interest in theater design. Superficially, at least, it’s easy to see this as cute, even silly, but a closer look reveals a sharply observant sensibility that critiques as much as it celebrates the people she depicts—including her family, her friends, and herself.

Impressed by the Ballets Russes’ production of “L’après-midi d’un faune” in 1912, Stettheimer conceived of her own ballet, based on the annual Four Arts Ball organized by the artists’ guilds in Paris. She worked on the project for years, writing the libretto and creating the set and costume designs, several of which are included in the show. She even made small model figures of some of the characters. Although the ballet was never produced, it was good preparation for her décor for Virgil Thompson and Gertrude Stein’s opera, “Four Saints in Three Acts,” which premiered at the Wadsworth Atheneum in February 1934 before moving to Broadway. This fabled example of avant-garde musical theater, with its all-black cast, Stein’s non-narrative libretto, and Stettheimer’s fanciful costumes and cellophane-draped set, was an unexpected hit and Stettheimer’s best-known work during her lifetime. A section of the exhibition is devoted to her costume designs, figurines, and other “Four Saints” memorabilia, including film (unfortunately silent) of a few scenes from the original Atheneum production.

Her paintings, however, were not well known until after her death in 1944. Her first and only lifetime solo exhibition, at Knoedler’s in 1916, was a failure—not one work sold—so she withdrew from the commercial art world. After that she showed in the annual Independents exhibition and displayed her paintings privately, further narrowing the audience for her increasingly eccentric depictions of life in her rarified milieu. Since there was no financial pressure on her, she was free to hold her work close, and even wrote in her will that it should be destroyed after her death. Fortunately her surviving sisters ignored that clause and distributed it to various institutions, including Columbia University and the Museum of Modern Art. Thanks to their gifts to these and other major collections, as well as posthumous solo shows at MoMA, the Whitney, and now at the Jewish Museum, Stettheimer’s curiously poetic sensibility has found its place in the modernist canon.

Rauschenberg Among Friends

8-3-17

When you conjure up the stereotypical 20th century artist, it’s a painter or sculptor toiling away in isolation. Occasionally he or she might design a theater set or illustrate a book of poetry, but only occasionally. An artist whose entire career was spent collaborating with others in the visual, literary or performing arts is rare indeed. Larry Rivers is one, and Robert Rauschenberg (1925-2008) is another. Born two years apart, they actively engaged with colleagues across genres to debunk the notion of art-making as a solitary pursuit. In part their rebellion was a reaction to Abstract Expressionism, with its emphasis on individuality and inward-looking inspiration, and in part it reflected their omnivorous curiosity and gregarious personalities, which were too expansive to be contained within the studio.

We are still waiting for the overdue comprehensive exhibition that will illuminate Rivers’ many and various collaborations, but Rauschenberg’s are currently being celebrated at the Museum of Modern Art, where “Robert Rauschenberg: Among Friends,” is on view through September 17. This vast show follows Rauschenberg’s career from start to finish, and even from day one he had a penchant for collaboration. Among the earliest works are blueprint images of the painter Susan Weil, whom he met while studying art on the GI Bill in Paris and married in 1950. Weil introduced him to the technique, which they used to make ethereal images of her body by direct exposure to the light-sensitive paper.

Another early example of communal activity is from Rauschenberg’s Night Blooming series. Painted in 1951 at Black Mountain College—a hotbed of interdisciplinary experimentation—the painting on view was also worked on by Cy Twombly, Rauschenberg’s lover at the time, who helped him apply asphaltum to the surface and impress it with dirt and gravel. According to the wall label, they were studying with Robert Motherwell, who encouraged them to add more debris, a Surrealist-inspired gesture that presages Rauschenberg’s use of chance, as well as unorthodox media and materials. This led to a series of montages with found objects that became known as Combines, which are among his best-known and arguably most important works. I don’t think there’s one that contains an actual kitchen sink, but pretty much everything else—from an umbrella in Charlene, 1954, to a stuffed angora goat in Monogram, 1955-59—is in there somewhere. His friends often contributed items for inclusion. Dorothea Rockburne gave him the patchwork quilt that he reworked in 1955 as Bed, and paintings by Weil and Jasper Johns became part of Short Circuit, also from 1955.

Many such multi-artist endeavors are now famous, and one is infamous: his 1953 Erased de Kooning Drawing. In what has been interpreted as a gesture of opposition to Abstract Expressionism, Rauschenberg asked Willem de Kooning for a drawing specifically to obliterate. De Kooning gave him a challenging one, a mixed-media work on paper that took him a month to erase, and even then not quite completely. Johns created a label for it, which is an integral part of the piece. Asked if the erasure was an act of defiance, or even vandalism, Rauschenberg dismissed the negative readings. “It’s poetry,” was his reply.

Poetry of another order inspired his 34 illustrations for Dante’s “Inferno,” made using solvent to transfer printed source material to paper. This technique, and the photographic screen printing he learned from Andy Warhol, features in many of his later canvases and collages, in which disparate imagery comments on the fraught political and social climate of the 1960s, as well as consumer culture. At the same time he continued actively to collaborate with choreographers Paul Taylor, Merce Cunningham and Yvonne Rainer, and worked with Billy Klüver, a Bell Labs engineer, on a project called Experiments in Art and Technology, E.A.T for short. The venture is represented by films of various E.A.T. events and happenings, and a re-creation of Mud Muse, a large pool of bubbling bentonite, activated by sound loops, that spatters you with liquid clay if you get too close. Not the most aesthetically pleasing of Rauschenberg’s collaborative creations.

The show includes works by many of Rauschenberg’s partners in art and life, from Weil, Twombly and Johns in the early days to videos of the Trisha Brown Dance Company, with which he collaborated from 1976-1995. Throughout his career he never stopped reaching out to creative people in whatever field intrigued him. As he summarized it, “My whole area of art has always been addressed to working with other people.”

“Visionaries” Who Created the Guggenheim

7-6-17

To celebrate the 80th anniversary of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, the founder’s eponymous museum is presenting “Visionaries,” a blockbuster survey of modern painting and sculpture drawn entirely from its own holdings, on view through September 6. Few other museums can boast such a comprehensive collection, especially one that depends almost entirely on the acumen and generosity of a handful of donors and patrons. In addition to Solomon himself, the show highlights five other individuals who, as the show’s subtitle has it, created a modern Guggenheim.

All six of the so-called visionaries came by that designation honestly. They were avidly collecting modern art when it was far from the blue-chip commodity it is today. Solomon, the fourth of Meyer Guggenheim’s eleven children, began buying pictures in the 1890s. He turned from Old Masters to contemporary art in 1929, under the guidance of Baroness Hilla von Rebay, an artist from an aristocratic German family who became the museum’s first director and whose own collection was left to the Guggenheim. It was she who commissioned Frank Lloyd Wright to design the controversial museum building on Fifth Avenue.

A champion of non-objectivity, Rebay steered Solomon toward Kandinsky. The exhibition is introduced by one of the masterpieces he bought early on, Kandinsky’s Black Lines, 1913, followed by a magnificent gallery devoted to the artist, with Solomon’s acquisitions supplemented by those of his niece, Peggy, and the dealer Karl Nierendorf—two more of the visionaries whose collections have been incorporated into the Guggenheim.

Both Nierendorf and Justin K. Thannhauser were German art dealers who immigrated to the United States and became major benefactors of the museum. Together their contributions added significantly to the original holdings, broadening their scope to include Impressionism, Post-impressionism, and German Expressionism. After Nierendorf died in 1947 the Guggenheim purchased his entire estate, which included not only Europeans like Klee, Kirchner and Albers but also the Americans Baziotes, Gottlieb and Fine. In 1963 Thannhauser bequeathed major paintings from his collection—with signature works by Cézanne, Van Gogh, Gauguin and Picasso—to the museum, which built a special wing to house them.

Katherine S. Dreier, a Brooklynite from a wealthy German émigré family, was bitten by the modernist bug while studying art in Europe in the 1910s. Advised by Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray, she founded the Société Anonyme in 1920 to promote modern art and amassed a substantial personal collection, some of which was donated to the museum by her estate. One of the highlights is Constantin Brancusi’s Little French Girl, made of oak, ca. 1914-18. The original Guggenheim collection included just a few sculptures, but in the 1950s, under the directorship of James Johnson Sweeney, an outstanding group of Brancusi wood and stone carvings was acquired. They are beautifully installed in a gallery of their own, with photo documentation of several of the pieces in the artist’s studio.

Many more riches were added in 1976, when Peggy Guggenheim’s collection became part of the foundation. It took some very diplomatic persuasion to convince Peggy to give her treasures to her uncle Solomon’s museum, since they didn’t get along. Still housed in her Venetian palazzo, the collection focuses on Surrealism and abstract art, from Arp to Vedova, with a healthy representation of the American avant-garde. Several of her key works have made the trip to New York for this special occasion, including Alchemy, 1947, one of the 11 paintings by Jackson Pollock that she kept for herself. A virtual unknown when Peggy became his patron in 1943, Pollock had his first solo show in her gallery, got his first mural commission from her, saw his first museum acquisition, and had her financial support while she launched his career.

Recently revitalized by a meticulous cleaning, which is documented in a separate exhibition in the museum’s education center, Alchemy is installed at the very top of the spiral ramp, literally capping the show. As much as any other work on view, it epitomizes the visionary spirit of the collectors who took risks on the novel, unproven, unpopular art that challenged established tastes. Their foresight did indeed create the Guggenheim as a monument to modernism.

“Making Space” for Women at MoMA

6-8-17

Spanning roughly 25 years, from the end of World War II to the rise of second-wave feminism, “Making Space: Women Artists and Postwar Abstraction,” at the Museum of Modern Art through August 13, is both fascinating and annoying. Drawn entirely from MoMA’s holdings, the exhibition showcases a wide variety of first-rate works in different styles and media, some of them recent acquisitions and several on view for the first time. That’s the fascinating aspect. The fact that MoMA owns so many outstanding works by female artists deserves notice. The annoying thing is that, instead of being integrated into the permanent collection installation, these fine examples of abstract art are segregated by sex. It’s a conundrum.

At the show’s entrance, Grace Hartigan’s big, bold 1957 canvas, Shinnecock Canal—painted while Hartigan was staying at Alfonso Ossorio’s Georgica estate, The Creeks—can hold its own beside any postwar action painting. MoMA acquired it soon after it was painted, as is the case with Joan Mitchell’s Ladybug, also from 1957, Helen Frankenthaler’s Trojan Gates, 1955, and Hedda Sterne’s New York, VIII, 1954. Here is evidence that the museum was not neglecting female Abstract Expressionists during the movement’s heyday. And they’re not minor examples, but signature works that show the artists’ virtuosity. So why not just mix them up with AbEx paintings by men?

This, of course, has been a longstanding complaint of those who count the number of women represented in MoMA’s collection galleries. They have a point, though some female artists are regular fixtures of the themed installations, from Russian Constructivism to Dada, Surrealism, AbEx, Pop art and beyond. Sculptures by Louise Bourgeois, Louise Nevelson and Marisol are never absent, and canvases by Lee Krasner, Agnes Martin, Bridget Riley and Yayoi Kusama are always up. But when you see the wealth of material that’s isolated here, it does make you wonder why so much of it has languished in storage. Lack of room seems like a lame excuse.

Not everything in “Making Space” is painting or sculpture, which actually is one of the show’s strengths. Recently the museum has begun to combine works from several departments—a different kind of integration that allows viewers to trace trends across media. Geometric abstraction, for example, is represented by Martin’s canvas, The Tree, Gego’s painted iron sculpture, Eight Squares, drawings by Anne Truitt, photographs by Gertrudes Altschul, weavings by Anni Albers and printed fabrics by Vera Neumann. By breaking down hierarchical distinctions, especially between fine art and craftwork, the show gives a truer picture of the multiple approaches to abstraction in the mid 20th century. That all the artists happen to be women is somewhat beside the point, since their male colleagues were working along similar lines.

Indeed, some of these artists, if they were alive, would have objected to being separated from the men. Krasner, for one. She even had a problem with being classified as an American artist, much less a female one. She once told an interviewer that, while she was obviously a woman and was born in America, those were not criteria by which her art should be measured. To her, and to others who find those distinctions irrelevant to aesthetics, the only criterion that matters is the work’s quality. In other words, not who made it, or the artist’s nationality, race, or sex, but whether or not it’s any good. Even for those with specifically feminist agendas, quality is the ultimate benchmark, but one that’s highly subjective. Those pesky categorical judgments, favoring paintings over prints and drawings, bronze over fiber, etc., further complicate the assessment process—as do changing tastes. It’s not uncommon for yesterday’s masterpiece to become tomorrow’s eyesore. That’s why the museum’s imprimatur is so important. If MoMA thinks something is worth exhibiting, it must be good.

So on the one hand the museum should be applauded for bringing to light such a stellar array, including pieces by artists from Europe, Asia and the Americas—some of them famous and others unfamiliar even to dedicated MoMA visitors. On the other hand, why aren’t they up all the time? As a curator, I think a more enlightening show would be one with a 51:49 female-to-male ratio. That would make the art world look more like the real world.

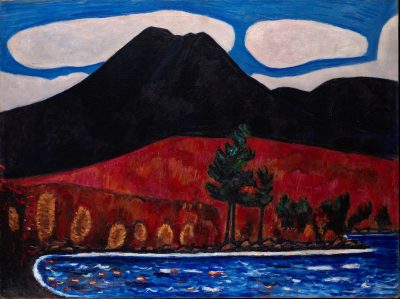

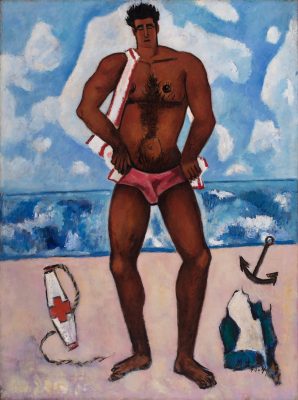

Marsden Hartley’s Maine

5-11-17

“I wish to declare myself the painter from Maine,” wrote Marsden Hartley in an essay that accompanied his 1937 exhibition at Alfred Stieglitz’s gallery, An American Place. This affirmation of devotion to his native state—he was born in Lewiston in 1877—is the raison d’être for “Marsden Hartley’s Maine,” on view through June 18 at the Met Breuer, in the former Whitney Museum building on Madison Avenue.

The exhibition spans the artist’s entire career, taking him full circle from his early figure drawings of local characters and neo-Impressionist Maine landscapes to his final series of paintings depicting Mt. Katahdin, which he claimed as his own, much as Cézanne did Mont Sainte-Victoire and Japanese artists did Mount Fuji. To emphasize the point, the installation includes a Cézanne lithograph and prints by Hokusai and Hiroshige from the Met’s collection that illustrate their treatment of those iconic subjects. In fact the Met owns two major Cézanne paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire, but apparently they couldn’t spare either one to represent a more pertinent relationship to the Hartley oils.

Perhaps it’s just as well, since Hartley suffers in direct comparison to artists like Cézanne and Winslow Homer, whose influence he acknowledged. The show is peppered with related examples from the Met’s holdings. Next to a trio of Hartley’s studies of waves beating against Maine’s rocky shore, Homer’s 1895 masterpiece, Northeaster, steals the show. In contrast to Homer’s luminescent breakers, Hartley’s waves are as static and opaque as plaster. The same quality is evident in his clouds, which often seem as solid at the hills over which they loom. To be fair, Hartley wasn’t a veristic painter aiming for fidelity to nature. His impulse was far more subjective, more akin to the Expressionists whose work he emulated in Paris, Munich, and Berlin before the First World War forced him back to the US.

After a disappointing 1909 debut at Stieglitz’s 291 Gallery, Hartley painted a series of so-called dark landscapes inspired by Albert Pinkham Ryder. Here’s a comparison that doesn’t diminish either artist: Hartley’s The Dark Mountain, 1909; and Ryder’s Moonlight Marine, painted and re-painted over a 20-year period, 1870-90. Both men approached landscape as a point of departure for emotional and spiritual themes, moody reflections on inner states of being. In Hartley’s 1938 portrait of Ryder, an homage painted two decades after the grand old visionary’s death, his gaze seems to turn inward and outward at the same time. A similar haunted stare is on Hartley’s own face in Stieglitz’s 1916 photograph of the artist, taken soon after his return from Europe.

Stieglitz captured Hartley’s inner turmoil following the death of his Prussian lover, Lieutenant Karl von Freyburg. Several of his 1914-15 abstract paintings, which are outside the scope of this exhibition, memorialize the handsome young officer, who was killed early in World War I. Needless to say, they didn’t go over well in New York after the US entered the war, and in 1917 Hartley went to Ogunquit, Maine, in part to reconnect with his roots and re-think his artistic direction. For the rest of his life he would travel widely, restlessly searching for an anchorage, but would always be drawn back to his home state, where he finally settled in 1937. Devoting himself to interpreting the land and its people, he fell in line with the prevailing quest for national identity that pervaded much Depression-era art. The very fact that Stieglitz named his third and last gallery An American Place indicates how even such a staunch Modernist responded to that trend.

Until his death in 1943, Hartley looked at Maine through the lens of a solitary, closeted gay man, couching his homoerotic imagery as celebrations of Yankee strength and resiliency. Aptly described in the gallery wall text as “hypermasculine rural hunks,” his fishermen, lumberjacks, and athletes are as solid as Maine’s rocks and trees. Yet his studies of harvested logs bound for the timber mills suggest the vulnerability of nature and symbolically of man—or, more literally, the young men who will soon march off to yet another world war. Echoes of Hartley’s long-lost lover add poignancy to the works that celebrate the virile male body so overtly.

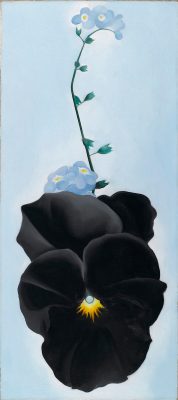

Fashioning Georgia O’Keeffe

4-13-17

In 1927, the Brooklyn Museum gave Georgia O’Keeffe her first solo museum exhibition. Ninety years later, she is again the subject of a solo show there: “Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern,” on view through July 23. This time, however, the focus is as much on O’Keeffe the person as on O’Keeffe the painter, using her clothing and personal effects as revealing clues to the woman behind the art.

In addition to her paintings, sculpture and works on paper, as well as copious photographic documentation, the show includes numerous examples of her garments and accessories from the collection of the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, which owns the artist’s two New Mexico homes, in Abiquiu and on the Ghost Ranch, where her possessions have remained intact since her death in 1986.

Dubbed “the best known woman painter in America” by Life magazine in 1938, O’Keeffe was then, and remains, a figure of individual as well as aesthetic fascination. Indeed, her self-constructed image—immortalized in black and white photographs by luminaries like Ansel Adams, Carl Van Vechten, Edward Weston, Cecil Beaton, and most famously her husband, Alfred Stieglitz—is an essential part of the package. Her sensuality comes across in Stieglitz’s intimate nudes, but with her clothes on she’s austere and aloof, projecting an uncompromising character that’s also strongly reflected in her wardrobe.

Two of the show’s earliest works are portraits of O’Keeffe in her early twenties, and in both she’s wearing black and white. This pared-down palette was her lifelong preference, though there are some notable variations, especially in her later years. Early on she sewed many of her own clothes, fashioning a look that was simple yet elegant. A group of four eggshell silk dresses from the 1920s and ’30s illustrates her skillful needlework and fondness for understated detailing. These garments are paired with paintings of the period. She and Stieglitz were living in New York and vacationing upstate, a locale that yielded some colorful canvases, but several others echo the monochromatic severity of her dresses and the black cloak, borrowed from Stieglitz, that she often wore.

After moving permanently to New Mexico in 1949, O’Keeffe favored store-bought work clothes for her rambles around the countryside in search of the scenery and found objects that became her primary subject matter. Her battered black Stetson, a pair of Levi’s, a denim apron, shirts, sneakers and a selection of bandanas are here, as is a beautiful squash blossom necklace she admired but seldom wore, preferring to hang it on the wall like a work of wearable sculpture. Her preferred accessories were a silver-studded black suede belt, visible in several photographs of her, and a brass brooch, custom made in the shape of her OK initials by Alexander Calder. She had custom-made clothing as well, by designers such as Knize, Emsley and Claire McCardell, with shoes by Ferragamo. The influence of Asian aesthetics is evident in several kimonos, also custom made for her from material she brought back from her travels.

O’Keeffe’s position as an independent woman who forged a distinctive persona, as well as the creator of a popular and highly prized body of work, was firmly established by 1977, when Perry Miller Adato made an award-winning film about her, and 1980, when Andy Warhol painted her portrait. Near the end of her long life—she lived to be 98—she was a truly iconic figure among American artists and an avatar for the burgeoning second wave of feminism. Already in her thirties by the time the 19th Amendment was ratified, she was old enough to remember the first wave.

The Brooklyn Museum’s tribute, organized by guest curator Wanda Corn, is part of a year-long celebration of the 10th anniversary of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. I wonder whether O’Keeffe would have approved of being grouped with feminists, or even considered a role model for them. She embodied the solitary genius—an indomitable spirit, fascinating in her remoteness—and played that role to the hilt, while acknowledging that it was Stieglitz who orchestrated her initial success. But once she was launched she capitalized on her early recognition, cultivated a carefully managed public image, and used the power of photography to put it across. Unlike any previous O’Keeffe exhibition, this one makes that persona come alive.

Inventing Downtown

3-16-17

Forty years ago, an exhibition titled “Tenth Street Days” revisited the cooperative galleries that flourished downtown during the 1950s and ‘60s, when so-called emerging artists were seeking alternatives to the uptown commercial gallery system. In 1977 that era was still fresh in the memories of those who had participated in the co-ops, Happenings and other phenomena that defined the scene. Since then lots of them have died, and the period has acquired an art-historical patina that is lovingly burnished in “Inventing Downtown,” on view through April 1 at NYU’s Grey Art Gallery on Washington Square, in the heart of the district in question. While the previous show was limited to co-op galleries and to paintings and sculpture, this one takes a wider view, including artist-run spaces that weren’t co-ops, as well as other media, such as installations, performances, photography and film.

Like the earlier Abstract Expressionists with lofts and hangouts on and around Tenth Street, those who came up in their wake sought safety in numbers. Also like their forebears, many of them gravitated to the Hamptons as a summer retreat. Wandering through the jam-packed NYU galleries, I was struck by the number of locals I recognized, among them John Chamberlain, Jim Dine, Dan Flavin, Perle Fine, Lester Johnson, Bill King, Fay Lansner, James Rosenquist, Stan Van Der Beek and Jane Wilson. Others whose work I was hoping to see—Anneli Arms, Alice Baber, Elaine de Kooning, Berenice D’Vorzon, Matsumi Kanemitsu, Athos Zacharias and Wilfrid Zogbaum—are not included, unless I missed them amidst the wealth of fascinating material, both artistic and documentary, that’s on display.

At the show’s heart are the Tanager, Hansa and Brata galleries, three of the co-ops that sprang up in the neighborhood’s cheap commercial rentals. Dues-paying members shared the expenses and the labor of putting on shows of their own work and that of invited guests. It was a fractious task, but out of the turmoil stars emerged, including Mark di Suvero, Yayoi Kusama, Philip Pearlstein, Allan Kaprow, George Segal, Alex Katz and several of the folks named above. Another co-op, the Phoenix, was co-founded by Red Grooms, who later opened his own loft as the City Gallery. Kaprow’s first Happening was at the Reuben Gallery, which he co-founded and where Grooms, Oldenburg, and Dine also performed. Found-object art and assemblage flourished in this atmosphere. Props for Happenings and installations were often scavenged from the street.

A hallmark of the current show is the diversity of styles and media that proliferated in the artist-run spaces, whether co-op, rented or borrowed. Judson Gallery, in Judson Memorial Church, was an especially fruitful venue for performance and installation art, including Oldenburg’s “The Street” (which later migrated to Reuben) and Dine’s “The House.” Judson’s “Hall of Issues,” organized by Phyllis Yampolsky, was an ongoing open call for material that attracted artists and non-artists alike. Such free-flowing engagement encouraged direct participation in which poets, musicians and dancers interacted with visual artists in a lively atmosphere of give and take. Among the notable genre-benders were Yoko Ono, who combined visual, conceptual, and performance art, and Robert Rauschenberg, a co-founder of Experiments in Art and Technology.

The exhibition also highlights the Spiral Group, a short-lived collective of African-American artists that coincided with the Civil Rights Movement. The group, which mounted only a single exhibition, in 1965, included such luminaries as Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis, and Hale Woodruff, who taught at NYU. Spiral’s brief history illuminates the larger debate about how art can respond to social and political issues without becoming propaganda.

Many Tenth Street alumni graduated to uptown galleries, and a couple of the co-ops actually moved uptown. The Green Gallery on West 57th Street evolved from Hansa—which had relocated to Central Park South before closing in 1959—and showed several of the downtown contingent, ranging from proto-Pop artists to abstract painters and minimalist sculptors. And moving up by no means meant selling out. Indeed, one of the goals of the downtown artist-run galleries and alternative spaces was simply to get the work seen and noticed, in the hope that it would be picked up by mainstream art dealers. Judging by the roster represented in “Inventing Downtown,” that was a strategy for success.

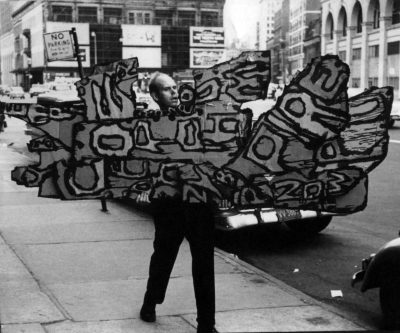

Pierre Chareau’s Legacy Explored

2-16-17

In Most Holy Trinity Cemetery on Cedar Street in East Hampton, a modest granite stone marks the grave of Pierre Chareau. How this became the final resting place of one of France’s premier Art Deco and Moderne designers is part of the story told in “Pierre Chareau: Modern Architecture and Design,” an innovative and revealing exhibition at the Jewish Museum in Manhattan through March 26.

Best known for a building in Paris called the Maison de Verre—House of Glass, which predates by two decades Philip Johnson’s much more widely known and accessible Glass House in New Canaan, Connecticut—Chareau came to the United States in 1940. Although he was raised Roman Catholic, his family was Jewish on his mother’s side and his wife, Louise Dorothée Dyte (1880-1967), known as Dollie, was Jewish. Fleeing Nazi persecution, they settled in New York, where Dollie taught French and Pierre tried unsuccessfully to re-establish his professional career, which had been primarily as a designer of furnishings and interiors. That line of work had already been curtailed by the Great Depression, when the market for sumptuous décor using exotic and costly materials had pretty much dried up.

Fortunately, in 1945 he was befriended by the artist Robert Motherwell, who commissioned him to design a house and studio in Georgica, using war-surplus Quonset huts. In lieu of a fee, Chareau built a small house for himself and his wife on the Motherwell property, and it was there that he had his fatal stroke. Hence his burial far from Paris, the city where his reputation was made and where his only surviving residence, the Maison de Verre, built between 1928-32, is still intact in private ownership. (After changing hands a couple of times, the Motherwell house was demolished in 1985.)

In addition to documentary evidence like plans, sketches, and photographs, Chareau’s legacy includes the handsome high-end furniture he designed for wealthy patrons in pre-World War II Europe, and works from the collection of modern art that he and Dollie assembled when they were members of the Parisian intelligentsia. The exhibition features a partial reassembly of that collection—including works by Picasso, Léger, and Mondrian—most of which was sold to support the couple during their expatriate years.

There are also examples of the furniture, among them a clever nesting telephone table; the “La Religieuse” lamp, named for its pointed glass shade that resembles a French nun’s headdress; and a “canapé a confident” sofa, originally designed for a 1923 film set and later prominently featured in the Maison de Verre’s interior décor. Many of these items were scattered during the war, when the possessions of Chareau’s Jewish clients were sold or confiscated.

Individual pieces of furniture can appear sterile when isolated and displayed out of their original settings, so the exhibition designers have used ingenious techniques to bring the material to life. Back-projected silhouettes show people sitting in chairs, working at desks and moving about in rooms, suggesting how real folks would interact with the furniture. But even more intriguing is the use of virtual reality to place some of the pieces in their former surroundings. In the central gallery, four stations offer head sets through which to view the furniture in situ, including the interior and garden of the Maison de Verre. In an adjoining room, a digital walk-through of the house affords viewers admission to a building that is hidden away from public access. This high-tech experience seems to me an especially fitting way to interpret a structure that itself is a marvel of modern engineering and gadgetry.

Lovingly restored by the current owner, Robert Rubin, an American businessman, the house was commissioned by Dr. Jean Dalsace, a gynecologist, who had his office on the ground floor. Shoehorned under an existing 19th century building, its front and back façades are made entirely of glass bricks that maximize the available natural light while maintaining the occupants’ privacy. One wall is punctuated by heavy louvered windows that open easily using a geared mechanism. With its steel structure exposed both inside and out, its frank exploitation of industrial materials, and its custom-made furniture and fixtures, Maison de Verre is one of the most iconic buildings few people have ever seen in person. This exhibition is as close as most of us will come to actually being there.

Beckmann in New York

1-19-17

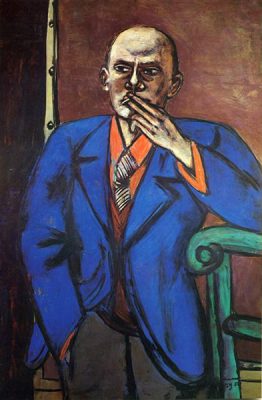

On December 27, 1950, a man collapsed and died during a walk from his West Side apartment to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The man was Max Beckmann, one of Germany’s foremost 20th century artists, and his destination was the exhibition, “American Painting Today,” which included his “Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket.” That painting is the centerpiece of “Max Beckmann in New York,” a stunning show of paintings he made there, supplemented by other works from New York collections, on view at the Met through February 20.

The multiple ironies in this undertaking probably would have amused Beckmann, a champion cynic and master of gallows humor. For one, he was out of place in the show he never got to see. He was not American, nor was his brand of painting in the forefront of contemporary art at the time. Having survived persecution and exile during the Nazi regime, which labeled his art degenerate and confiscated it from German museums, he died of a heart attack in a city where he was perfectly safe and where his art was prized by important collectors. And this tribute, which opened 66 years after his death at age 66, includes a painting that was foolishly deaccessioned by the Met.

Beckmann moved to New York City in 1949 and spent only 15 months there, but many of his paintings had preceded him. The Museum of Modern Art already owned his major triptych, “The Voyage,” which puzzled me as a youngster and continues to fascinate. Dealers J.B. Neumann and Curt Valentin were placing his pictures in prestigious private collections. He was teaching at the Brooklyn Museum Art School and, inspired by a milieu he found as stimulating as prewar Berlin, painting up a storm. But he was not seduced by New York’s glitz and glamor. True to his nature, he also saw the darkness, both in those around him and in himself.

We are introduced to Beckmann by a group of seven self-portraits, including the blue-jacket one, inscribed “NY 50,” which proved to be one of his last works. Leaning on an armchair, puffing the ubiquitous cigarette, a brilliant orange shirt peeking out from underneath his cobalt coat, the artist appears introspective, as if mulling over ideas for a new painting, or perhaps deciding where his urban rambles would take him next. He was his own favorite subject, and this gallery shows us some of the many personae—one might say disguises—he assumed. His costumes range from conservative to theatrical, formal to casual, including a tiger-striped outfit for himself as a bugler in 1938, sounding a warning against Fascism’s rising tide.

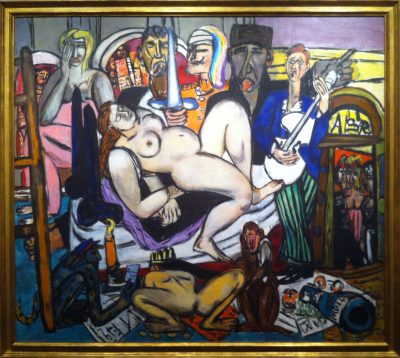

Unlike some other German exponents of New Objectivity, Beckmann’s social and political critiques are metaphorical rather than literal, more general than topical, using familiar visual landmarks and personal symbolism to comment on the human condition. Recurring images include lighted candles, often with phallic overtones, that can mean both revealing light and burning pain; ladder-like shapes that may represent escape routes or confining bars; bound and mutilated figures, sometimes inverted, implying a world turned upside down by cruelty and oppression. His characters are not caricatures, like those of Grosz or Dix, but are often actors in tragicomic settings, wearing their costumes and makeup and playing roles in public or domestic dramas.

This is complicated art, requiring some decoding in order to appreciate its deeper meanings. In “Bird’s Hell,” 1938, for example, a crowd of feathered monsters flashes the Nazi salute as one of them carves up a human victim. The blue demon that pops out of an egg is a symbol of the warped ideology hatched by Hitler’s megalomania. “The Town (City Night),” 1950, features a cast of grotesques attending a human sacrifice replete with sexual symbolism, while a monkey in a messenger’s cap holds the artist’s calling card. I’m here, he says, and I’m watching this travesty of a party—but strike up the band, and bring on the dancing girls! It’s a reminder that, even in New York, a city he loved, Beckmann sensed human folly behind the civilized façade.

On a personal level, Beckmann’s brief sojourn in the city had lasting significance for me. Apart from the magnificent legacy of his art, he left money to the Brooklyn Museum Art School to establish a scholarship in his name. I received one, and at the same time so did the handsome young man from England who became my husband. I think Beckmann would have been pleased to learn how that turned out.