My “Eye On Art” column appears monthly in the Sag Harbor Express

“Monsters and Myths” in Hartford

12-27-18

Salvador Dalí once remarked that, “according to Nostradamus the apparition of monsters presages the outbreak of war.” For Dalí and his fellow Surrealists, however, the demons they conjured were not only premonitions but also reflections of past and present horrors. Arising in the aftermath of World War I, the movement expressed the resulting social and political upheaval, reacted to the rise of Fascism in Europe in the interwar period, and both foreshadowed and responded to the renewed conflict of World War II. Those themes are explored in “Monsters and Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s,” on view through January 13 at the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford, Conn., after which it will travel to the Baltimore Museum of Art and on to the Frist Art Museum in Nashville, Tenn.

The Wadsworth and Baltimore were early collectors of Surrealist art, and the show draws heavily on their holdings, supplemented by loans from other museums and private collections. Unfortunately, for logistical reasons, not all the works are going to all three venues, so a few key things are missing from the Wadsworth, including major canvases by Arshile Gorky and Yves Tanguy, both of whom lived in Connecticut, as did André Masson. Tanguy and his wife, the American Surrealist painter Kay Sage, settled in Woodbury; Gorky committed suicide on his property in Sherman in 1948.

Masson, who left France in 1941 and sat out the war in New Preston, is well represented by several paintings, heavy on both mythological and monstrous imagery, made before and during his American sojourn. So is Max Ernst, who also emigrated in 1941; Dalí, who had come to the U.S. a year earlier; and his fellow Catalonian, Joan Miró, whose garishly sinister 1937 canvas, Still Life with Old Shoe, is among the show’s responses to the Spanish Civil War. In contrast to Picasso’s The Dream and Lie of Franco etchings, which grotesquely caricature the Nationalist general as a grinning polyp-head, and Dalí’s bizarre Soft Construction with Boiled Beans, in which a mutilated figure claws at itself and writhes in agony, Miró’s symbolism is not explicitly anti-war. Like pathetic artifacts in a smoldering, bombed-out building, the abandoned shoe and the remnants of a meal poignantly convey the conflict’s human toll.

When World War II broke out, many of the artists were subject to persecution, displacement, and exile. Those labeled by the Nazis as degenerate or otherwise undesirable were forced to flee. Ernst, a German who had been living illegally in France for years, was interned as an enemy alien, but escaped and was brought to the U.S. by Peggy Guggenheim. Remarkably, a major painting from that period, Europe After the Rain II, started while Ernst was on the run, was shipped to him in care of the Museum of Modern Art (where his son, Jimmy, was working) and was finished in New York. A sequel to his 1933 depiction of the continent devastated by the earlier war, it is a complex allegory based on the Greek myth of Europa’s abduction by Zeus in the form of a bull.

In Ernst’s ghastly panorama, the creature and its human cargo are ossified within the ruins of a temple-like structure, an allusion to European civilization destroyed by the “rain” of bombardment. The surroundings, derived in part from the fantastic rock formations Ernst saw in Sedona, Arizona, are equally ravaged. This masterpiece, with its echoes of hellscapes by Grünewald and Bosch, was acquired early on by the Wadsworth, as was Roberto Matta’s Prescience, 1939, a collection of fragmented forms in an acidic landscape, and Dalí’s Apparition of Face and Fruit Dish on a Beach, 1938, a trompe l’oeil memorial to the Spanish poet García Lorca, who was executed by Nationalists in the early days of the civil war.

Among the Americans associated with Surrealism, in addition to Sage, are Robert Motherwell, Dorothea Tanning, Jackson Pollock, David Hare, Mark Rothko and Alexander Calder, and examples of their work are included. Not all were card-carrying members of the group, but each felt the influence of its precepts, especially spontaneous inspiration arising in the unconscious. In practice, however, as the exhibition illustrates, the Surrealists’ imagery was often based on conscious awareness and actual experience. Their nightmares had come true, and their monsters were real.

Nature’s Nation

11-29-18

America’s attitude toward the natural world, at once reverential and adversarial, is the subject of “Nature’s Nation: American Art and Environment,” a wide-ranging exhibition, on view through January 6, at the Princeton University Art Museum. Its title is taken from an essay by the late historian Perry Miller, who traced the development of American identity as fundamentally determined by our relationship to nature, and the inherent conflict between the need to conquer the wilderness and respect for the land’s wonders and bounty.

Using more than 120 examples of art, decorative arts, and artifacts spanning four centuries, the show illustrates creative responses to the environment from different cultural perspectives. This soup-to-nuts approach allows for the inclusion of everything from antique household goods to contemporary video, organized in three epochs: Colonization and Empire, Industrialization and Conservation, and Ecology and Environmentalism.

The introductory display contrasts Albert Bierstadt’s painting, Bridal Veil Falls, an early 1870s celebration of Yosemite’s magnificent cascade, with Valerie Hegarty’s Fallen Bierstadt, an ironic revision that has the painting literally disintegrating, as if damaged by a fire or flood, or eaten by insects. Is it nature’s revenge on man-made beauty, or conversely, a comment on humankind’s destructive impact on the environment? Paintings by Bierstadt and Thomas Moran helped convince Congress to create the national park system, yet these natural treasures are constantly under threat from commercial development and incursion.

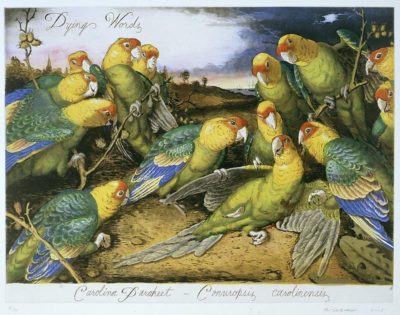

Seen through the lens of what’s billed as “ecocriticism,” even celebratory images and useful objects appear in a new light. Exquisite 18th century items made of silver are shown to be products of slave labor in hellish conditions. The manicured formal garden backdrop for a Colonial portrait testifies to the desire to tame nature’s unruliness. An 1820s Audubon rendering memorializes the colorful Carolina parakeet, the only U.S. native parrot, later killed off by the clear-cutting of its habitat. Walton Ford recalls that loss in Dying Words, a 2005 etching based on The Death of General Wolfe, Benjamin West’s 1771 requiem for a fatally wounded British general surrounded by his troops. In Ford’s clever re-conception, the extinct birds replace the soldiers.

The exhibition would be a hodgepodge without extensive interpretive material. Numerous text panels and long labels explain each item’s critical context. This makes for slow going through the galleries, but patience is rewarded by many revelations. For example, Jervis McEntee’s 1858 painting of the barren terrain that became New York City’s Central Park is paired with a large plan of the park’s roadways, water features, and other amenities. What neither view shows is the African-American community that was displaced by Vaux and Olmsted’s picturesque improvements—you need the label to give you that information.

Human impact on nature, for better or worse (mostly worse, as the show has it), accelerates in the 19th and 20th centuries as a consequence of Westward expansion, urbanization and industrialization, symbolized by John Gast’s American Progress, an 1872 allegory of Manifest Destiny. As so-called civilization advances, it seems the quality of life declines. For every idyllic forest, majestic mountain and glorious sunset, there’s a burning oil well, polluted river, urban wasteland and ugly open-pit mine. The near extinction of the buffalo is well represented as a cautionary tale, contrasting indigenous people’s respect for the creatures, both as sustenance and as spiritual beings, with their wholesale slaughter by settlers. The impact of armed conflict, unchecked exploitation, and disasters brought on by bad management practices echoes down the generations, from the Civil War to the Dust Bowl and beyond, but are we listening today?

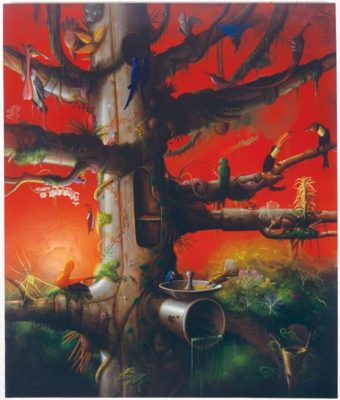

The consequences of not listening are suggested by Alexis Rockman’s Aviary, a dystopian vision of perverted evolution. With more than a passing nod to Hieronymus Bosch, Rockman imagines the tree of life as an open sewer pipe, its dead branches colonized by invasive plants and populated by grotesque hybrid birds. An eerily intense glow pervades the scene, as if the sky itself were toxic. This may be an illustration of what we can expect if we don’t pay attention to the just-released climate change report, which only makes the message of “Nature’s Nation” all the more timely.

Jack Whitten, Secret Sculptor

11-1-18

Shortly before his death this past January, Jack Whitten agreed to an exhibition primarily devoted to his sculpture, a body of work known only to his family and close friends. After its premier at the Baltimore Museum of Art in the spring, “Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963-2017” is now on view through December 2 at the Met Breuer. We’re fortunate that, near the end of his life, Whitten invited us to visit his secret garden of earthly delights.

An abstract painter who came of age in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the art world was dominated by Minimalism and Conceptualism, Whitten persisted in the subjective, improvisational spirit of the Abstract Expressionists. Far from following in their footsteps, however, he developed his own vocabulary of sensuous forms and tactile materials, including dragged pigment and acrylic-chip mosaics. According to ARTnews, his “process-based canvases pushed abstraction into new territory.” But while his paintings have been widely exhibited, his sculptures remained sequestered in his New York studio and on his property on Crete, where he began summering with his Greek-American wife, Mary, in 1969. Like Odysseus, the voyager invoked in the exhibition’s title, his artistic journey took him far from home.

Whitten was born in 1939 in Bessemer, Alabama, a steel town near Birmingham. To escape the South’s racism, which he referred to as “American apartheid,” at age 21 he moved to New York City and graduated from The Cooper Union in 1964. While still a student, he began experimenting with sculpture inspired by his African-American heritage. In the current show, his two “Jug Head” carvings reference both African masks and the grotesque 19th century face jugs made by enslaved potters in the rural South. Examples from the Met’s collection, well know to the artist, are included for comparison.

Indeed, the show is rich in such juxtapositions, illustrating Whitten’s adaptations of indigenous African and Mediterranean precedents. Several of his wood pieces are studded with nails, wire, razor blades and other sharp metal objects, paraphrasing Congolese nkisi power fetishes, one of which is also on view. Homage to Malcolm, 1965, for example, memorializes Malcolm X following his assassination. More than six feet long, constructed of wood and found objects, the sculpture’s head end is encrusted with nkisi-like elements, clearly linking the subject to his African forebears. At the other end, a curving shape suggests a blade, or perhaps the sharpness of the slain activist’s rhetoric.

Several of Whitten’s “Black Monolith” abstract mosaic portraits, including those of the authors Ralph Ellison, Maya Angelou and James Baldwin, and the musicians Ornette Coleman and Chuck Berry, are also in the show. Like them, his nkisi-inspired carvings pay respects to figures he admired, from John Lennon to his Aunt Surlina. Among other droll touches, his tribute to the kri-kri, a type of wild goat native to Crete, prominently features his expired American Express credit card. A series of reliquaries contain bones from the island’s fish and birds; in one, a lock of his wife Mary’s hair is tenderly preserved. Two carvings are dedicated to his daughter, Mirsini. Effigies, totems, masks and weapons from other cultures and eras are mined for their potent symbolism and adapted to serve the artist’s fruitful imagination.

Considering how personal such works were to Whitten, and that he kept them from public view for decades, it’s no exaggeration to describe his sculptural practice as a labor of love: love for the materials themselves, and love of the physical act of transforming them from their natural state into works of art. Much of the wood comes from the area around his studio in Agia Galini, the Cretan village where he built a summer home in the mid 1980s. Using only hand tools, skillfully blending historical references with contemporary themes—sometimes whimsical, sometimes confrontational, and sometimes deeply spiritual—he fashioned what amounts to a multi-faceted monument to his experience of the places and the people he cherished.

Davis and Krasner Together

10-4-18

Apart from resting peacefully near each other in Green River Cemetery in Springs, what do the painters Stuart Davis and Lee Krasner have in common? Judging by their best known works—his geometric, hers gestural—not much. Yet there was a time when they were both aiming toward similar artistic goals. Their point of confluence was during the Great Depression of the 1930s, when they were employed by the WPA Federal Art Project and designed murals for WNYC, New York’s municipal radio station, and other public buildings. Both were then strong adherents of Cubism, Davis having absorbed it first-hand in Paris and Krasner having come to it as transplanted to New York by her teacher, Hans Hofmann. But while Davis stuck with it, adapting it to his own, singularly American, point of view, Krasner veered off in a more subjective direction, becoming one of the foremost abstract expressionist painters of her generation.

Their brief period of agreement is illustrated in a pair of complementary shows at Kasmin Gallery’s two showcases in Chelsea, which represents both artists’ estates—a coincidental commonality that allows the gallery to present them in tandem. “Lee Krasner Mural Studies” is at the 297 Tenth Avenue space, while across 27th Street is “Lines Thicken: Stuart Davis in Black and White,” at 293 Tenth Avenue. The Davis show is on through Dec. 22. The Krasner show closes on Oct. 27, the 110th anniversary of her birth.

Last year, Kasmin’s show of Krasner’s so-called Umber series concentrated on the late 1950s and early 1960s, when she delved into deep emotional territory in large canvases that fairly boiled with painterly energy. They were highly personal statements, whereas twenty years earlier, her ambition, which she shared with Davis, had been to paint wall-filling works for a mass audience, and to do it in a flat, neo-Cubist style. As a WPA muralist, she was assigned to decorate buildings, first as an assistant to more experienced artists and finally, in 1940, on her own. Kasmin is showing eight gouache studies she made that year for a specific, though unknown, location—probably a school, library or hospital—identified only by blank areas indicating the architectural elements she had to work around.

Krasner’s approach to this assignment ranges from exuberant to restrained. The influence of predecessors like Matisse, Arp and Miró is evident, but, like Davis, she has internalized and adapted their lessons. In some examples, brightly colored biomorphic shapes cavort across the wall, jostling one another playfully, as if inviting spectators to join in the dance. In one, however, the mood is cool and formal. Carefully balanced rectangles structure the space, but a kidney-shaped loop relieves the design’s geometric purity. Sadly, none of these concepts made it to the wall for which they were intended. Nor did her 1941 proposal for the WNYC Studio A mural, though many sketches and studies survive.

Davis, on the other hand, did complete various mural projects in the 1930s, including two for the WPA: “Swing Landscape,” intended for a housing project but later acquired by the Indiana University Art Museum; and one for WNYC’s Studio B, which was removed and donated to the Met. A study for his first mural is a highlight of the Kasmin show. “Men Without Women,” a pre-WPA commission, was painted in 1932 for the Radio City Music Hall’s men’s lounge. The linear ink and pencil version lacks several of the male attributes in the finished work, which now lives at MoMA, but three dominant motifs—a tobacco pipe, sailboats and a horse—are present in skeletal form. The drawing shows how meticulously Davis planned his compositions, shifting and adjusting elements until he achieved the ideal balance. He was a brilliant colorist, and when that chromatic richness is stripped away his mastery of structure becomes all the more evident.

From the show’s largest works on canvas to the smallest drawings, Davis was endlessly inventive, even as he played variations on themes and reprised many of his subjects. Nautical scenes and maritime paraphernalia, observed in New York harbor or in the seaside port of Gloucester where he summered, gave him plenty of raw material, as seen in several of the works on view. And a charming drawing that pays homage to the jazz drummer George Wettling represents another of his long-term inspirations. That’s another thing Davis and Krasner had in common—they both loved jazz.

Brancusi’s Reality at MoMA

9-6-18

According to Constantin Brancusi, “What is real is not the appearance, but the idea, the essence of things.” That attitude is fundamentally modernist, and Brancusi was at the forefront of such thinking in the early 20th century. His remarkable personal and artistic journey from rural Romania to avant-garde Paris is encapsulated in a small but captivating exhibition on view through February 18 at the Museum of Modern Art. It includes all 11 of MoMA’s Brancusi sculptures, shown together for the first time, as well as photographs of his studio and documents related to the collection. Only one piece is on loan from an outside source.

This is not the largest holding of Brancusi’s work in the United States. That distinction belongs to the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which owns 19 sculptures and many vintage photographs of the artist and his studio. Nor is it comprehensive, lacking examples of such iconic works as The Kiss and Princess X, of which he made multiple versions. That said, the show is a focused, intensive look at Brancusi’s visionary approach to three-dimensional form—an imagination so radical that in 1926 the U.S. Customs Service famously refused to classify one of his sculptures as art. Two bronze versions of that piece, Bird in Space, are in the current show. The problem for customs officials was that it didn’t look like any bird they’d ever seen. That was the point. It’s meant to convey the spirit of flight. They also held that it appeared to be industrially produced rather than hand made. Brancusi successfully argued that each piece was hand crafted and unique. Indeed, though there are nine bronze versions of this form, no two are identical, as the examples on view prove. Like many of his works, they are variations on a theme.

A master of direct carving in wood and stone, Brancusi is best known for his Endless Column, a vertical stack of four-sided pyramids, arranged point-to-point and base-to-base. MoMA owns the earliest surviving example, a 1918 oak piece just under seven feet tall. Originally the artist used the pyramid module as a pedestal for other works, but at some point he saw it as a form in its own right, capable of perpetual repetition. Its most ambitious adaptation is a 98-foot steel tower, erected in 1938 in a sculpture park in Târgu Jiu, Romania, to honor the soldiers who defended the city against a German force during World War I. By contrast, MoMA’s piece is intimately scaled but no less monumental in concept. Its chiseled surface has a tactile quality that attests to the sculptor’s hands at work.

The show’s earliest example of Brancusi’s carving prowess is Maiastra, and it’s singular in a couple of ways. The top section, dated 1910-12, is his first sculpture of a bird, inspired by a creature in Romanian folklore. Its sleek, stylized marble form sits atop a limestone cube supported by an earlier, roughly hewn carving of two caryatids, which in turn rests on a boxy limestone pedestal. Caryatids—supporting figures in Greek classical architecture—are usually female, but here their sex is uncertain and their bodies struggle to emerge from the stone. This section dates from about 1908, and it’s the first time Brancusi used one sculpture as the support for another. He would continue that practice throughout his career, and considered the pedestals to be integral parts of the sculpture, often combining different materials and treatments to create complementary ensembles. In Blond Negress II, for example, the polished bronze head sits on a four-part base made of wood, limestone, and marble, incorporating all four of his most commonly used materials.

Although the Negress’ head was inspired by an African woman Brancusi saw at a colonial fair in Marseilles in 1922, it’s not a literal portrait. Always striving for the essential reality beneath superficial appearance, he has abstracted her features and eliminated details. This is also true of Mlle. Pogany, his study of a young Hungarian artist who became the subject of several variations. In MoMA’s bronze version, a dark patina defines her hair, but there are few other clues to her individuality. Her tilted head rests on her hands in a dreamy pose, and it’s hard to tell if her huge almond-shaped eyes are open or closed. This kind of ambiguity is a hallmark of Brancusi’s approach, which invites the viewer to share his vision of a deeper, more universal truth.

Witness Creativity at Artists’ Homes

8-9-18

The beautifully restored Thomas and Mary Nimmo Moran home and studio in East Hampton, recently opened under the aegis of the East Hampton Historical Society, is a tangible reminder of the important role a specific environment can play in the creative process. Both Thomas and Mary looked out the window for inspiration. She made many etchings of local scenery, and while he’s best known for his paintings of the Yellowstone, he also pictured the bucolic charm of the village and its surroundings. Some of those images are on view in the museum’s inaugural exhibition, which also interprets the two artists’ lives and careers.

The Moran studio isn’t the only property where you can get a sense of the artists’ relationship to the places they inhabited. There are 36 of them in the Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios coalition of sites across the country, from Ukiah, CA to Portland, ME. You’ll find them on the group’s website, artistshomes.org. The northeast is especially rich, with several sites within a day’s drive from Sag Harbor and one, the Pollock-Krasner House, just down the road in Springs.

A ferry ride to the Connecticut coast and a short hop west to Old Lyme will take you to the Florence Griswold Museum, billed as the home of American Impressionism. When the Griswold mansion became a boarding house in the late 19th century, it attracted plein-air painters who set up their easels on the spacious grounds and decorated the dining room wall panels with colorful souvenirs of their stays. In addition to the original 1817 house, there’s a modern museum building with changing exhibitions and an impressive permanent collection of work by Lyme Art Colony notables, including Childe Hassam, whose East Hampton home and studio, Willow Bend, is privately owned and not open to the public.

A ferry ride to the Connecticut coast and a short hop west to Old Lyme will take you to the Florence Griswold Museum, billed as the home of American Impressionism. When the Griswold mansion became a boarding house in the late 19th century, it attracted plein-air painters who set up their easels on the spacious grounds and decorated the dining room wall panels with colorful souvenirs of their stays. In addition to the original 1817 house, there’s a modern museum building with changing exhibitions and an impressive permanent collection of work by Lyme Art Colony notables, including Childe Hassam, whose East Hampton home and studio, Willow Bend, is privately owned and not open to the public.

For immersion in America’s take on Impressionism, travel west to Cos Cob, where another former boarding house, the Bush-Holley House, was a destination for landscape painters, including Hassam and J. Alden Weir, in the early 20th century. Then go north to Weir Farm National Historic Site in Wilton, one of two national parks devoted to artists. (The other is the Augustus Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site in Cornish, NH.) In addition to Weir’s home and studio, it includes the studio of sculptor Mahonri Young, Weir’s son-in-law. The ubiquitous Hassam was a frequent visitor, as was Albert Pinkham Ryder, who painted the local scenery. Contemporary artists are invited to work on the 60-acre property and apply for month-long residencies.

The Hudson River valley also boasts a cluster of artists’ homes, crowned by Olana, a 250-acre estate with a Persian-inspired mansion overlooking the river in Hudson, NY. This magnificent setting, the creation of Frederic Edwin Church, inspired some of his most famous landscape paintings, several of which are on permanent display inside the house. The place is remarkably preserved, with its original furnishings and décor, encapsulating the artist’s world with complete authenticity. Nearby, in Catskill, is the home of Church’s mentor, Thomas Cole, dean of the Hudson River School. Although not as intact as Olana, it nevertheless conveys Cole’s relationship to the terrain that provided the subject matter for his most renowned paintings.

The Hudson River valley also boasts a cluster of artists’ homes, crowned by Olana, a 250-acre estate with a Persian-inspired mansion overlooking the river in Hudson, NY. This magnificent setting, the creation of Frederic Edwin Church, inspired some of his most famous landscape paintings, several of which are on permanent display inside the house. The place is remarkably preserved, with its original furnishings and décor, encapsulating the artist’s world with complete authenticity. Nearby, in Catskill, is the home of Church’s mentor, Thomas Cole, dean of the Hudson River School. Although not as intact as Olana, it nevertheless conveys Cole’s relationship to the terrain that provided the subject matter for his most renowned paintings.

Just across the New York-Massachusetts border are two major sites, which, like Olana, were purpose-built to the artists’ specifications. The Frelinghuysen-Morris House and Studio in Lenox, MA, is a classic modernist design, built in 1941 for the abstract painters Suzy Frelinghuysen and George L.K. Morris. While neither of them was inspired directly by the surrounding landscape, their home is a testament to their aesthetic outlook. With its original furniture, interior and exterior murals, and the couple’s collection of modern art, it’s an outstanding example of a domestic setting that’s a work of art in its own right.

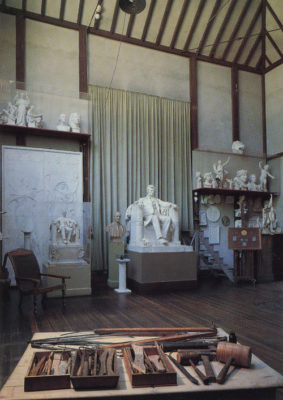

Similarly, at Chesterwood, Daniel Chester French’s property in nearby Stockbridge, you’ll find the custom-built studio where French crafted many of his prominent public sculptures, including the statue of Abraham Lincoln in Washington, DC’s Lincoln Memorial. Inside the studio, the artist’s tools, maquettes, and scale models illustrate the creative process at first hand. This is the real thing, not a Disneyfied re-creation.

Similarly, at Chesterwood, Daniel Chester French’s property in nearby Stockbridge, you’ll find the custom-built studio where French crafted many of his prominent public sculptures, including the statue of Abraham Lincoln in Washington, DC’s Lincoln Memorial. Inside the studio, the artist’s tools, maquettes, and scale models illustrate the creative process at first hand. This is the real thing, not a Disneyfied re-creation.

These sites, and the 27 others in the Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios coalition, offer extraordinary opportunities to experience the special character of the artists’ workplaces and gain insights into their personal and professional lives. As the group’s slogan has it, “come, witness creativity.”

Giacometti’s Singular Vision

7-12-18

Alberto Giacometti was, by all accounts, a driven man, one devoted to making art even as he considered it a discouraging enterprise. As he told his friend James Lord, who posed for him in 1964, “I’ve been wasting my time for thirty years.” Such self-deprecation goes way beyond modesty to the very core of Giacometti’s dilemma. He wanted to capture the truth of his observations, but that goal remained elusive. “All I can do,” he once complained, “will only ever be a faint image of what I see.”

The current Giacometti retrospective exhibition, on view through September 12 at the Guggenheim, makes me grateful to the artist for having failed so magnificently. He may have perpetually disappointed himself, but his paintings, drawings and sculptures never disappoint the spectator willing to engage with them. They convey a profound sensitivity to the human condition, as well as distinctive means of expressing that empathy.

The show—the first such overview in New York since MoMA’s in 2001-02—includes works on loan from the Fondation Giacometti that have never before been shown in the US. It traces the evolution of his singular vision with true inclusiveness, from a naturalistic oil portrait of his brother Diego and early carvings influenced by Oceanic and Cycladic sculptures to the iconic figures of his last two decades, topped off by a film of the artist at work in his Paris studio in 1966, the year of his death, still striving to resolve his own self-imposed contradictions.

Born in 1901 into a Swiss family of artists, Giacometti moved to Paris in 1922 and spent most of his career there. His early sculpture reflects the impact of Cubism, and of vanguard sculptors like Brancusi, Lipchitz and Picasso, who also looked to tribal and ancient art for inspiration. Working from memory rather than from observation allowed his imagination free rein and brought him to the attention of the Surrealists, with whom he became associated in the early 1930s. Examples like “Woman with Her Throat Cut,” “Disagreeable Object” and “The Palace at 4 a.m.” (the actual sculpture is at MoMA, but a fine sketch is included) show the combination of whimsy and menace found in so many Surrealist works. But he soon abandoned Surrealism’s reliance on dreams and the unconscious and returned to working from live models, especially Diego, whose studio was adjacent to his.

During World War II Giacometti lived in Geneva, where he made tiny plaster figures, so small and fragile that, he said, they actually frightened him. It’s also where he met Annette Arm, who would become his wife and frequent model. After returning to Paris in late 1945, his response to the war’s aftermath was to attenuate his figures, using a combination of modeling and carving in the three-dimensional works. It’s hard not to see echoes of concentration camp victims in the skeletal bodies, many of which are trapped in boxes or cages, harking back to his Surrealist works, or mounted on isolating plinths. He once likened his slender figures to trees in a forest, but they look more like the remains of a forest fire than like living trees. In the painted portraits, his obsessive revisions scar the features of his solitary subjects, which are usually rendered in greys and blacks and enclosed in claustrophobic spaces.

Giacometti was far from the only artist to respond to the postwar malaise by depicting humanity as damaged and alienated—among sculptors, Germaine Richier and Zoltan Kemeny come to mind—but his own statements don’t address such intentions. Instead he spoke of wanting to distill the essence of his observations of actual people in contemporary settings, either encountered in the street or posing for him in the studio. But as strongly as he expressed his need to capture what he saw in the world around him, his view was deeply personal. In fact it appears that the angst his subjects embody so effectively is not theirs, but his. Their rootedness—those huge feet anchored to the earth, unable to propel even the walkers—symbolizes his own inability to progress creatively, at least as he perceived it. I believe it was his inner life that dictated the compulsive reductionism that strikes such a responsive chord in our present age of anxiety.

Chaim Soutine: Flesh

6-14-18

“Flesh,” Willem de Kooning famously declared, “was the reason why oil paint was invented.” Besides de Kooning himself, no one bears out that contention more convincingly than Chaim Soutine, whose voluptuous studies of dead animals are the centerpiece of a small but stellar exhibition on view at the Jewish Museum through September 16.

By 1949, when de Kooning made his pronouncement, Soutine’s work was represented in important American museums, most extensively at the Barnes Collection in Merion, PA, to which many artists made pilgrimages. The following year a major retrospective was presented in New York at MoMA. From portraits and still lifes to landscapes and tableaux of meat, fish and fowl, Soutine’s subjects, no matter how static, seem to writhe on the canvas. A younger generation of painters, de Kooning included, responded to the painterly exuberance and emotive power of his brushwork, which invests even lifeless forms with vital energy.

Soutine was born in a Jewish village in Lithuania in 1893. The area was routinely subject to anti-Semitic violence during his childhood, when he also witnessed the ritual slaughter of animals according to Jewish dietary laws. These formative experiences are said to have decisively influenced his artistic development. Somehow—not explained in the exhibition—he managed to study art for three years at the academy in Vilnius, after which he moved to Paris and into a coterie of Jewish émigré artists who befriended and encouraged him. His association with other figurative painters, especially Modigliani, no doubt reinforced his devotion to representation, albeit with his own singular approach to traditional subjects. One of the show’s earliest works, from about 1916, is a study of Cité Falguière, the ramshackle studio building they shared. He had already adopted the energized brushstrokes and flattened perspective that became hallmarks of his mature style.

Turning from that modest canvas, one is confronted by Still Life with Rayfish, and confronted is the word. The composition is based on a painting of the same subject by Chardin that Soutine saw in the Louvre, where he studied the Old Masters intensively. Compared to the 18th century painter’s restrained, matter-of-fact approach, Soutine’s treatment is shockingly dramatic. Hanging from a hook, the dead fish, its beady eyes and gaping mouth emphasized, is splayed out like a huge livid fan. Its entrails spill onto a table, where they mingle with a pile of blood-red tomatoes. The whole arrangement seems to tilt forward and down, as if about to land at your feet. Like many of Soutine’s portraits of dead creatures, it’s both repulsive and fascinating, drawing you in with its remarkable subtlety and formal sophistication while grossing you out with its literally visceral directness.

By the time Soutine painted the ray, around 1924, he no longer had to worry about money. After years of grinding poverty, when meager arrangements of fruit and dried fish doubled as the artist’s meals, Albert Barnes had set him up for life by buying more than 50 of his paintings all at once in 1922. One of them is in the exhibition. The usual still-life motifs—a bottle, a plate of vegetables, etc.—include a bizarre piece of green pottery in the shape of a duck, placed upside down, with its neck broken. This symbolism foreshadows the images of plucked chickens and turkeys in the next gallery, where Soutine takes the time-honored dead-game genre into uncharted emotional territory. This leads to a group of his iconic paintings of beef carcasses, inspired by Rembrandt’s The Flayed Ox but far more gory and grotesque. Rembrandt left out the blood and guts. Soutine did not.

Of course it was then common to see plucked fowl, skinned rabbits, and sides of beef hanging in butcher shops, but Soutine invested such subjects with a kind of grisly pathos. The tactility of the paint, as well as its dynamic application, emphasizes the material itself, dissolving the forms sometimes to the point of illegibility. Then they stubbornly reassert themselves with alarming frankness.

One kind of flesh notably absent is the human variety. Soutine painted many portraits, but none are included here. You can see some on the Barnes Collection’s website. They round out a picture of the artist as an inspiration for generations of figurative expressionists, from de Kooning and Francis Bacon to Alice Neel, Lucien Freud and Cecily Brown. Like Soutine’s, their interpretations of flesh uphold de Kooning’s premise.

“Anything Goes” at the Nassau County Museum

5-17-18

In his 1971 book, Living Well is the Best Revenge, Calvin Tomkins tells the story of Gerald and Sara Murphy, expatriate Americans living in France in the 1920s. In many ways the Murphys—who later lived on Sara’s family estate, Dunes, in East Hampton—personify the Jazz Age, as chronicled in “Anything Goes,” the current exhibition at the Nassau County Museum of Art in Roslyn Harbor. There’s a lot to take in, so be sure to allow yourself ample time to savor the show’s many gems. Among them—not counting the exquisite Art Deco jewelry by Tiffany and others—is a delicate 1923 ink portrait of Sara by Picasso.

The Murphy circle, a who’s-who of the avant-garde, included Picasso, Léger, Cocteau, Goncharova and Stravinsky among the Europeans, as well as Hemingway, Dos Passos, MacLeish, Fitzgerald and other Americans who gravitated to the artistic ferment of interwar Paris. This confluence of talent in various artistic disciplines, from the visual and literary arts to music, theater, dance and fashion, sparked collaborations and encouraged experimentation. The exhibition’s curator, Charles A. Riley II, has woven these creative strands together, illustrating the interrelationships among them.

While the American artists were picking up on Cubism, Orphism, Syncromism and other assorted isms pioneered in France, Europeans audiences were taking to jazz in a big way. On the literary front, Sylvia Beach, an expat from New Jersey, ran Shakespeare & Company, a Paris bookstore that promoted the latest in vanguard poetry and fiction, famously including works like Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Ulysses that were banned in America. Examples of such publishing milestones are on display.

Portraits by the American photographer Man Ray depict several members of the international circle, from Gertrude Stein and James Joyce to Coco Chanel, Kiki of Montparnasse and members of the Ballets Russes, for which Gerald and Sara Murphy once painted scenery. Individual galleries are devoted to Gaston Lachaise, the French-born sculptor who immortalized his American wife Isabel in idealized monumental nudes, and the British-American painter Anna Walinska, who sketched Picasso in Paris in 1928. Collages by the German artist Kurt Schwitters have their counterparts in works by Americans Charles Green Shaw, Gertrude Greene and her husband Balcomb Greene. In the visual arts at least, who influenced whom is not really in question, since it’s obvious that the Europeans were the innovators. Yet Americans like Shaw, Joseph Stella, John Marin, Albert E. Gallatin, Arthur Dove, Betty Parsons and Stuart Davis acquit themselves admirably, building on the foundation laid by Picasso, Léger, Miró and other European modernists.

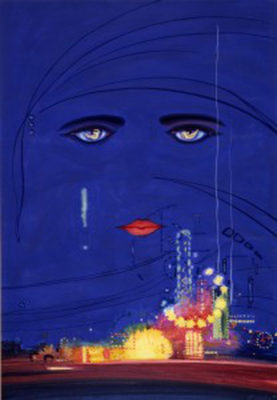

In other areas, however, the Americans stand head to head with their European counterparts. Hemingway and Fitzgerald in particular represent a new wave of writers whose voice is distinctively American. Another of the show’s highlights is the original 1925 cover art for Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, a midnight blue fantasy by Francis Cugat (brother of bandleader Xavier Cugat), in which a pair of disembodied eyes floats above a glittering carnival scene. A nude female form is curled within each eye’s iris, suggesting a bared soul reflected in the haunting gaze. Fitzgerald saw this design while he was still at work on the book, prompting him to use it as the basis for Nick Carraway’s image of Daisy Buchanan—another example of literary-visual art cross pollination.

In music, too, the Americans established a singular beachhead among the European vanguard while benefiting from interaction with trendsetters like Satie and Stravinsky. George Gershwin and Cole Porter both worked jazz syncopation into their compositions, marrying popular and classical forms to create new contemporary music, epitomized by Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and An American in Paris. Porter wrote music for Within the Quota, a 1923 Ballets Suédois production with sets and costumes by Murphy and a character, the Jazz Baby, based on Zelda Fitzgerald.

In music, too, the Americans established a singular beachhead among the European vanguard while benefiting from interaction with trendsetters like Satie and Stravinsky. George Gershwin and Cole Porter both worked jazz syncopation into their compositions, marrying popular and classical forms to create new contemporary music, epitomized by Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and An American in Paris. Porter wrote music for Within the Quota, a 1923 Ballets Suédois production with sets and costumes by Murphy and a character, the Jazz Baby, based on Zelda Fitzgerald.

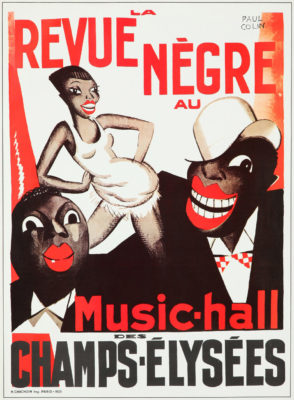

The most striking visual souvenirs of jazz’s impact on European culture are the posters by Paul Colin for various Paris cabaret acts, most sensationally those of the African-American expat Josephine Baker, who danced nude except for a miniskirt made of bananas. Shamelessly exploiting the appeal of “primitive” and “exotic” jazz rhythms, Baker’s Revue Negre took Paris by storm. Some of these graphics are decidedly racist by today’s standards, an issue that the show addresses head-on with an invitation to consider the art in its period context. That period is beautifully evoked in this wide-ranging exhibition, for which the title of Porter’s 1934 musical, “Anything Goes,” is the perfect description.

Antonakos’s Art of Light

4-19-18

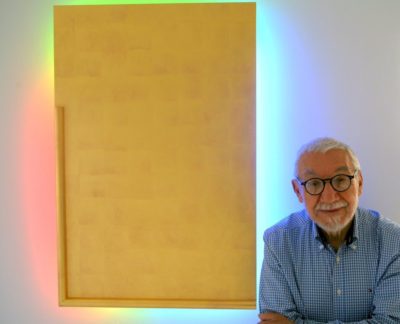

When residents of this village think of neon lighting, the iconic façade of the Sag Harbor Cinema is the first image that comes to mind. While we wait for that glow to illuminate Main Street once again, let’s remember another link between neon and Sag Harbor: the artist Stephen Antonakos, whose use of gas-filled glass tubing as a medium is being celebrated at the Neuberger Museum, on the campus of SUNY’s Purchase College, which commissioned his Proscenium light sculpture in 2000.

Antonakos, who for many years had a home on Hempstead Street and is buried in Oakland Cemetery, was born in Greece and came to New York with his family when he was four. After working as a commercial illustrator, he turned to fine art in the early 1960s. In those days his artwork was collages, assemblages, and a series of pillows that he modified in various ways, including adding lighted elements to them. The last pillow in the series featured the word DREAM in neon and led Antonakos to explore the possibilities of using illumination as a medium in its own right.

Unlike artists such as Tracey Emin and Glenn Ligon—whose word-based works are featured in the Neuberger’s current show, “Bending Light: Neon Art 1965 to Now,” Antonakos used neon tubes as a means of expressing intangible concepts. Although early on he prowled Times Square at night for inspiration, he was not interested in neon as signage. As he once wrote, “I simply thought so much more could be done with it abstractly than with words and images.”

By the mid 1960s Antonakos’s neons were being included in group exhibitions around the country, and he had his first solo show at the Fishbach Gallery in New York in 1967. It was a time when experimental media were breaking down traditional barriers between fine and applied art, and Antonakos wasn’t the only artist working with light. Neon pieces by Bruce Nauman, Joseph Kosuth, Keith Sonnier and Antonakos’s fellow Greek-American Chryssa, as well as fluorescent light installations by Dan Flavin and Robert Irwin and argon-lighted panels by Mary Corse were regular features of contemporary gallery and museum shows.

Neon’s viability for outdoor signage was well established, and from the early 1970s on Antonakos adapted it for exterior commissions in the United States and abroad. For many years his Neon for 42nd Street, a series of sweeping red arcs with blue backlighting, completed in 1981, could be seen on New York’s West Side, and his 1990 Neon for the 59th Street Marine Transfer Station is still in situ. There are also outdoor and indoor installations of his light works in cities around the United States and in Greece, France, Israel, Italy, Germany and Japan.

Antonakos’s first commission for the Purchase campus was Neon Lintel (1997), which is suspended at the end of the covered walkway leading to the Performing Arts Center. Three years later, the college offered him a much more ambitious project, a site-specific installation for its Theater Gallery. Named for the stage area of a classical Greek theater, Proscenium frames the gallery on three sides. It comprises several individual elements, with both front and back illumination, totaling 189 feet in length, starting and ending with red and green arcs. They complement each other in both form and color, with red complementing green and the upturned arc complementing the downturned one. In between are straight and wavy neon tubes set in painted channels called raceways that contain and concentrate the light within them. Behind them, the backlighting makes the forms appear to float along the gallery walls.

Sitting in the darkened space, surrounded by the neon glow playing off the walls and reflective floor, is an intensely visual experience. According to the artist, that was his intention—to “connect with people in real, immediate, kinetic and spatial ways.” There is no message, other than the realization of a sensory response to the luminous surroundings. In other words, Proscenium is not a neon sign but an optical signal that stimulates inner awareness of what Antonakos called “a more intense, heightened kind of experience.”

Both Proscenium and its companion show of neon works by eleven other artists, including Ligon, Chryssa, Emin and Sonnier, will be on view through June 24.

Joseph Cornell’s Obsession

3-22-18

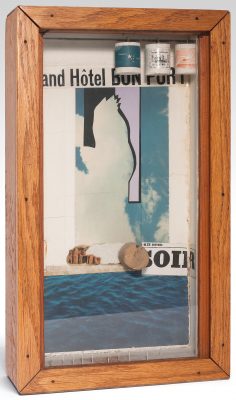

In October 1953, Joseph Cornell went to see an exhibition of modern paintings at the Sidney Janis Gallery on 57th Street. One painting in particular caught his eye. He was so entranced by The Man at the Café, a 1914 canvas by Juan Gris, that over the next thirteen years he made twenty-one homages to it—eighteen of his famous boxes, two collages, and one sand tray. (His sand trays are shallow boxes containing loose sand, shells and other objects, displayed flat. One wonders whether he got the idea for such constructions on his frequent visits to his sister in Westhampton, where he often walked along the shore.) According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the Gris painting and twelve of Cornell’s related boxes are on view through April 15, this is the largest number of works he dedicated to any of the luminaries he admired, including notable figures in the literary, performing and visual arts, from long-dead French poets to glamorous movie stars.

Cornell recorded his wide-ranging enthusiasms in diaries and correspondence with friends, selections of which were published in 1993. Several entries note his continuing obsession with the Gris, which depicts a faceted dissection of a man, wearing a brimmed hat, seated at a table and reading a newspaper, who casts his shadow on the wall behind him. It includes a collaged piece of real newspaper and faux wood graining on the wall and tabletop, as well as impastoed white paint pock-marked to indicate the foam on the man’s beer. The painting is part of Leonard A. Lauder’s treasure trove of Cubist masterworks, a promised gift to the Met, and it’s included to show just what it was that inspired Cornell.

The earliest Gris-themed boxes date immediately after Cornell’s encounter with the painting and incorporate direct references to some of its essential elements. The shadow cast by the man’s figure, the faux wood-grain surfaces, and the newspaper’s headline in French are all echoed in one of the first, Homage to Juan Gris, 1953-54. Instead of a man, however, the central figure is a perching cockatoo, referencing Cornell’s longstanding fascination with birds. His aviary boxes are like taxidermy display cases—though the birds are cutout reproductions, not stuffed specimens—in which each is given a unique habitat filled with clues to its symbolic meaning. The backgrounds are often papered with pages from French textbooks, hotel stationery, and other printed matter that reflects Gris’ residency in Paris. The use of letterhead from L’Hôtel d’Etoile could also be a way of acknowledging Gris’s status as the star of the show, and the bird itself may represent the creative freedom that Cornell perceived in the Spanish artist’s work.

That Cornell considered Gris a kindred spirit is evident, both in his statements and his efforts to express his admiration through these miniature enchanted environments. Some were made right away, others were started, then set aside and revisited years later. Le Déjuner de Kakatous, for example, was begun in 1959 and finished in 1966. It incorporates collaged fragments of a Gris painting cut from one of Cornell’s art books, which are displayed in a separate case. These artifacts are just a small sampling of the myriad of raw material he collected for his art, the way a magpie picks up odds and ends for its nest. He wasn’t a hoarder, but rather a sorcerer who could transform the most mundane objects into intriguing tableaux by working his magic on them.

After several years’ hiatus from his Gris obsession, on December 19, 1959 Cornell wrote in his diary of a renewed interest, perhaps due in part to the major Gris retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art the previous year but more directly sparked by reading John Golding’s book on Cubism. “What an unfoldment—the new color of Juan Gris,” he wrote, “plus box just this week lifted from doldrums with new blues (cloud shape of cockatoo).” Could this be Grand Hôtel Bon Port, dated to the late 1950s and notable for its silhouette of the white bird against a collage of a cloud-flecked blue sky? This diary snippet illustrates the artist’s love of wordplay—“blues” meaning both doldrums and colors—and its visual analogy, in which the bird becomes a cloud-like floating form. Or perhaps, per a later diary note, Grand Hôtel Bon Port is the “new Gris done on Xmas day especially as related to day after Xmas—early morning experience,” since the entry also mentions “the touch of orange” that we see in the French postage stamp. As with all of Cornell’s work, the viewer is invited to follow the clues wherever they may lead.

Tennessee Williams, Troubled Genius

2-22-18

Sunday will be the 35th anniversary of the death, in 1983, of Thomas Lanier (Tennessee) Williams, one of America’s greatest 20th century dramatists. His career is being celebrated in a revealing exhibition, “Tennessee Williams: No Refuge but Writing,” on view through May 13 at the Morgan Library & Museum in Manhattan. It takes its title from a 1981 statement by the author, who wrote almost compulsively, as if it protected him from his demons. “I try to work every day,” he said, “because you have no refuge but writing.”

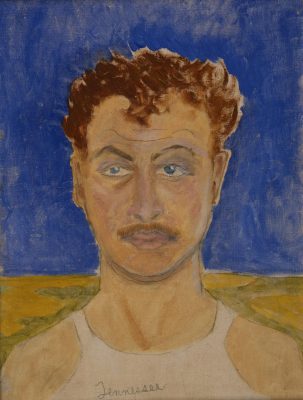

In addition to his full-length and one-act plays, Williams wrote short stories, poetry, essays, screenplays, novels and a memoir, and kept a journal that he mined for ideas. As the exhibition shows, he often re-worked material, transferring characters and situations from one genre to another. He was also a visual artist, though his oil paintings and watercolors are, to put it generously, not up to the level of his writing, as you can see in his self-portrait from about 1939. The following year, his first staged production, “Battle of Angels,” closed in Boston after being panned by the critics. Four years later, however, “The Glass Menagerie,” with characters based on Williams’ controlling mother and schizophrenic sister, won the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award for best play of the season and his career was launched. For the next 20 years his plays dominated Broadway, earning him rave reviews, two Pulitzer Prizes, and a Tony Award.

The show focuses on several of Williams’ most famous theatrical works, but it ranges widely across the literary and personal history of a complicated, driven, self-destructive genius whose own conflicts supplied his dramatic material. While he denied using specific autobiographical events, he acknowledged that his work reflected his emotional currents. Elia Kazan, who directed several of his plays, once remarked that “everything in his life is in his plays, and everything in his plays is in his life.”

Here’s an example close to home. In 1957 Williams visited Larry Rivers in Southampton, and they went out to dinner at the Tucker Mill Inn, the former Claflin mansion on what is now the Stony Brook Southampton campus. The windmill on the grounds was used as a guesthouse, and Williams decided to rent it for the summer. While there, he began work on a one-act play, “The Day On Which A Man Dies,” loosely based on the character of Jackson Pollock, whom he knew from summers in Provincetown in the early 1940s. Pollock—another troubled, self-destructive genius—had died in a car crash the previous summer, and Williams, who had once tried to kill himself that way, considered the artist’s death to be a suicide. Using his own experience and psychic state as springboards, he eventually created a highly stylized drama about a suicidal painter, based on Noh form, a tradition to which he was introduced on a trip to Japan in 1959.

The play was set aside and remained unknown for decades, though Williams adapted some of the material for his 1969 production, “In the Bar of a Tokyo Hotel,” which flopped on Broadway. After his death it was discovered among his literary effects, and was first staged in Chicago in 2008, after which the Pollock-Krasner House presented it at the Ross School, in conjunction with our 2009 Japanese Gutai exhibition. Its action, which includes full-body painting and the penetration of a paper wall, echoes the Gutai practices that were illustrated in the exhibition.

But “The Day On Which A Man Dies” is not one of the Williams works featured in the Morgan show, so why am I writing about it? The reason is the current production of “Pollock,” a one-acter by the French playwright Fabrice Melquiot, on through Sunday at the Henry Street Settlement’s Abrons Arts Center. Having seen “Pollock” immediately after the Morgan show, I couldn’t help but compare it to Williams’ daring experimental drama, which supplements incisive dialogue with creatively manipulated color and movement to explore complex emotional territory. “Pollock,” on the other hand, is a cliché-ridden, one-dimensional portrait of his marriage to Lee Krasner, ninety minutes of foul-mouthed conflict with no nuances or ultimate resolution. Entire sections of dialogue are lifted almost verbatim, and without credit, from Naifeh and Smith’s Pollock biography. To sum it up, as a playwright Melquiot is to Williams as Williams the self-portrait painter is to Rembrandt.

David Hockney’s Progress

1-25-18

To say that David Hockney has been around is putting it mildly. His peripatetic life and personal experiences in Europe, Asia, and the United States, where he has lived on an off for half a century, have been the sum and substance of his work since his days at London’s Royal College of Art. The chronicles of those public and private journeys are now on display in “David Hockney,” an exhibition that commemorates the artist’s 80th birthday, on view through February 25 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Misleadingly described in the Met’s media release as a major retrospective, the exhibition is far from a complete survey of Hockney’s long and illustrious career. It neglects his illustrated books and prints, such as A Rake’s Progress, his suite of 16 autobiographical etchings inspired by William Hogarth, which made a great stir in the early 1960s with its faux naïve style and explicit homoerotic content. It also ignores his theater décor. Nevertheless, it spans the full six decades of his work, from 1960-2017, and shows both his versatility and his virtuosity as a painter, draftsman, photographer and experimenter with visual technology.

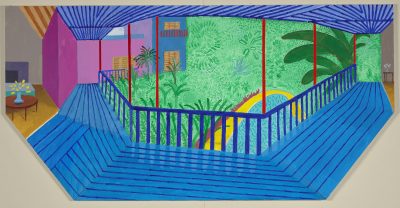

Looking at Hockney’s colorful, decorative canvases of the past 20 years, especially his homages to the lush tropical garden and brightly painted woodwork of his home in the Hollywood Hills, it’s easy to forget how transgressive his early work was. The first gallery offers a sampling of paintings from his student days that illustrate his precocious sophistication. They include motifs from popular culture—proto Pop art, if you like—and graffiti, expressed in an idiom that synthesizes gestural abstraction and cartoon-like stylization. Witty renderings of consumer products, from a packet of his mum’s favorite Ty-Phoo tea, incongruously inhabited by a nude male figure, to Colgate toothpaste tubes as phallic symbols, the imaginative flights of fancy delve deep into the artist’s gay psyche. Homosexuality was not decriminalized in Britain until 1967, so such imagery was daring, not to say shocking, outside the hidden world of the gay subculture.

Hockney’s frank depictions of homosexual themes were to some degree made more palatable by the deliberately primitive way he rendered them. Simplified forms, flattened perspective and a crude drawing style made them seem somehow guileless, like the honesty of a child blurting out uncomfortable truths in public. In his California paintings from the following decade, for example, this approach gives his pictures of naked men showering or displaying themselves provocatively an emotional distance, a coolness that blunts their eroticism. Many of the later 1960s and ’70s canvases further explore this idea of detachment, especially the double portraits of intimates, who seem more apart than together. Others are literally composed of detached motifs, like Rocky Mountains and Tired Indians, a montage of images—or maybe imaginings is a better term—inspired by trips to the American Southwest and Switzerland.

If anyone thinks that Hockney’s reductive draftsmanship indicates a lack of skill, a wall of his drawings dispels that notion. He could draw like Ingres if he chose to, as we see in his sensitive character studies from life, including W.H. Auden, Andy Warhol, John Kasmin and the artist’s parents. Three of the drawings were made in 1999 with the aid of a camera lucida, an apparatus that reflects an image onto the surface on which the artist works. Hockney’s fascination with mechanical visual aids is well known. His admirable open-mindedness and curiosity has led to interesting experiments with various devices, such as the Polaroid camera and the iPad, both of which are represented here by successful examples. The camera lucida drawings, however, are failures, lacking the vitality and immediacy of his earlier, more spontaneous works on paper.

Unlike the titular character in Hogarth’s A Rake’s Progress, Hockney has gone from strength to strength. From his early success as a leader of the generation of British artists whose brash irreverence was the visual-art counterpart of the Beatles, to his recent iPad drawings, shown as a three-panel animation that channels Matisse in the digital age, his powers of invention and adaptation seem inexhaustible. If some of his detours, like the silly so-called “V.N.” paintings and garish 1990s landscapes, have led him off course, he quickly gets back on track by returning to the California of his dreams and his reality. Yes, it’s eye candy, but how sweet it is.