Art Waves commentaries, 2004-2009: A Selection

© 2010 Helen A. Harrison. No reproduction without permission.

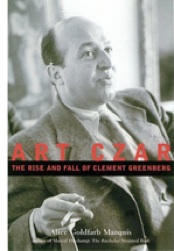

Art Czar

Broadcast 1/18/07

For this latest look at the life and career of the man widely regarded as the most influential American art critic of the 20th century, the author, Alice Goldfarb Marquis, had access to Greenberg’s papers, which were bought by the Getty a few years ago. Apparently he never threw away a single scrap of paper, and Marquis struck more than one rich vein in that particular gold mine. Two especially valuable sources are the drafts and revisions of his articles, reviews and lectures, including lots of unpublished material, and his journals, which give a day-by-day account of his social and professional life, and often of his moods as well.

Another treasure trove is his correspondence with a college friend, Harold Lazarus, which were published in 2000 as “The Harold Letters.” If ever there was a case to be made for burning one’s youthful ramblings, these letters make it–and Marquis, a visiting scholar at U. Cal. San Diego, uses them extensively to prove what a creep Greenberg was, pretty much from the get-go.

Another treasure trove is his correspondence with a college friend, Harold Lazarus, which were published in 2000 as “The Harold Letters.” If ever there was a case to be made for burning one’s youthful ramblings, these letters make it–and Marquis, a visiting scholar at U. Cal. San Diego, uses them extensively to prove what a creep Greenberg was, pretty much from the get-go.

This is not a long book, and I felt that there was more to the story than I was given–hell, I know there was. Both Marquis, and Greenberg’s previous biographer, Florence Rubenfeld, came to the Pollock-Krasner House to do research, since we have relevant material in the archives. He was, after all, one of Jackson Pollock’s most ardent champions, and was a frequent visitor to the house while the artist was alive. He came back for a talk to our Stony Brook graduate students in 1991, three years before his death, and that was the only time I met him. By then he was physically frail, racked by emphysema, but mentally alert, sober and still feisty–although he was better behaved than I’d expected, given his reputation as a combative and even insulting speaker, as well as a mean drunk.

Marquis wades deep into these murky waters, ascribing much of Greenberg’s arrogance and bluster to–here we go again–Jewish self-hatred. Yes, the Harold letters contain ample evidence of his disdain for his co-religionists, yet he worked as an editor of a Jewish magazine, and maintained that every word he ever wrote was a reflection of his Jewishness. He also expressed plenty of disdain for Gentiles, homosexuals, artists and women–no indication of his feelings for small furry animals, but since they have heartbeats he probably wasn’t too fond of them, either. So maybe the guy was just a neurotic screw-up with a non-denominational chip on his shoulder.

Certain aspects of Greenberg’s public life have already been thoroughly rehearsed, including his adversarial relationship with his fellow critic Harold Rosenberg, his involvement in the art market, which some people accused him of manipulating to benefit the artists he favored, and his high-handed attitude toward the sculpture in the estate of David Smith, of which he was an executor. But other, more intimate, things, like the unbalanced state of mind often revealed in his journal entries, and the insecurity illustrated by the obsessive self-criticism of his own writings and statements, haven’t been so thoroughly examined before, and they really make you wonder how the guy got to be so powerful.

On that point I have to quibble with the book’s title, “Art Czar.” Yes, it’s catchy, but it implies that Greenberg occupied an imperial position in the art world, with an army of defenders at his command. On the contrary, he was a lonely voice crying out in a philistine wilderness, even during his heyday in the 1940s and 50s, and even moreso after the advent of Pop art opened the floodgates to the sort of lowbrow kitsch he despised.

As long as I’m quibbling, there are also some careless mistakes in the book, like the wrong name for an important organization founded in 1936, the American Abstract Artists, which Marquis says continued until the 1960s but in fact still exists, and for Solomon Guggenheim’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting. She also gives the wrong date for the opening of his niece Peggy’s avant-garde gallery, Art of This Century.

She writes that there was only a single museum of modern art in the United States in the 1940s, inexplicably forgetting about the Phillips Collection in Washington, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, not to mention the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. She dismisses Pollock’s parents as “what we would now call trailer trash,” but they were nothing of the sort–they were hard-working property owners. And she maintains that Pollock wasn’t able to cash in on the publicity from a profile in Life magazine, but a few pages later she notes, quite correctly, that he sold a record number of works from the show he had three months after the article appeared. Sounds to me suspiciously like cashing in.

To be sure, these are minor shortcomings in a biography that’s otherwise well written and carefully researched, although the end notes aren’t as comprehensive as I would wish. Maybe the problem is more with the subject than with the author. Marquis’s Greenberg left me feeling ambivalent–wanting to know more about the world he lived in, but feeling I now know more than I want to about the kind of man I wouldn’t care to know at all.

For “In the Morning,” I’m Helen Harrison.