All posts by Helen Harrison

An Artist for our Victory

Art Waves commentaries, 2004-2009: A Selection

© 2010 Helen A. Harrison. No reproduction without permission.

An Artist for our Victory

Broadcast 12/29/05

When President Bush finally declares victory in Iraq, which artist will be called on to commemorate America’s military triumph? A recent NPR story about the Bayeux Tapestry got me thinking about art that celebrates war, which is in fact much more common than anti-war art. It’s found in all cultures, and there’s so much of it because the victors commission it and put it in prominent places.

The Bayeux Tapestry, which now has its own museum in France, is a chronicle of the Battle of Hastings in 1066. The winner was William of Normandy, who went on to conquer all of Britain. It’s really not a tapestry at all, but an embroidered strip of fabric, 230 feet long, that was probably created at the behest of William’s half brother soon after the victory.

A couple of hundred years earlier, in central Mexico, the Eagle Clan was beaten by the Jaguar Clan, who hired fresco painters to commemorate the slaughter of the defeated warriors, life size and in gory detail, on the walls of the great pyramid at Cacaxtla, facing out so everyone could see it. Here are vivid pictures of what you can expect if you dare to challenge the winners’ authority. Go back another 2000 years to ancient Egypt, and you’ll find plenty of temple friezes, like the magnificent ones in Luxor, celebrating the Pharaoh’s triumphs in battle, whether or not he was actually there in person.

In the 18th century, when the Chinese emperor built himself a summer palace in Beijing, he had the building’s long corridor lined with big paintings of famous historical battles that show the rulers defeating the would-be usurpers. And when the fledgling United States erected a capitol building in the early 19th century, the government hired the painter John Trumbull to depict the surrender of Lord Cornwallis’s army at Yorktown, which ended the American revolution. This time the usurpers won, and they weren’t slow to realize the propaganda value of reminding everyone who passed through the rotunda that they owed their liberty to the brave officers and stalwart troops whom Trumbull tactfully cleaned up for the ceremony–where, incidentally, Cornwallis was a no-show.

So who will be our Trumbull for the twenty-first century? We don’t have anyone with experience, since we’ve been a bit short on military victories for the past sixty years. Felix de Weldon’s sculpture of Marines raising an American flag on Mount Suribachi, on February 23rd, 1945, marks the last time we could honor our warriors unequivocally. So when we finally declare ourselves the winners in Iraq, who can we turn to for an appropriate memorial?

I nominate Red Grooms [left], whose current exhibition at the Nassau County Museum of Art in Roslyn Harbor shows that he has all the right credentials. He could give us a great battle scene, full of action and incident, packed with colorful characters, and above all tinged with ironic wit. His sense of theatrical absurdity is just what we need to commemorate our current misadventure.

I nominate Red Grooms [left], whose current exhibition at the Nassau County Museum of Art in Roslyn Harbor shows that he has all the right credentials. He could give us a great battle scene, full of action and incident, packed with colorful characters, and above all tinged with ironic wit. His sense of theatrical absurdity is just what we need to commemorate our current misadventure.For “In the Morning,” I’m Helen Harrison.

Public Art

Art Waves commentaries, 2004-2009: A Selection

© 2010 Helen A. Harrison. No reproduction without permission.

Public Art

Broadcast 3/2/06

After the mural or sculpture is unveiled, after the dignitaries make their speeches, after the donors are thanked and the ribbons are cut, who is responsible for taking care of the works of art that grace our public spaces? All too often, little thought is given to maintenance. Like the buildings and civic spaces they occupy, the artworks can deteriorate if they aren’t properly cared for. But they need a special kind of care, which their stewards, all too often, are not equipped to provide.

The point was brought home in a recent article in the New York Times Long Island section, which reported on condition problems with the murals in the auditorium of the Setauket Elementary School. Here is a case of well-meaning intervention gone wrong. After being removed, cleaned and restored, at a cost of $50,000, the murals were returned to the auditorium, which had been renovated and enlarged. But the improvements to the building were not good for the murals. Improper installation and unsuitable environmental conditions now threaten their long-term survival, and the cash-strapped school is not about to spend the money to create museum-quality climate control. Given its educational priorities, and a budget that doesn’t include a line for art conservation, how can the school be expected to deal with this problem?

This question is by no means unique to Setauket Elementary. In the 1930s, hundreds of public buildings around the country, from court houses and post offices to schools, libraries, hospitals, housing projects–even prisons and sewage treatment plants–acquired artwork commissioned by the various art programs of the New Deal. Technically, these pieces are still owned by the federal government, which financed their creation, but just try to get Uncle Sam to pay for their upkeep. Under the current administration, pious as they are, you haven’t got a prayer.

Even privately financed public art, like the imposing monument commemorating the founding of Smithtown, Long Island [right], is often the victim of benign neglect. Charles Rumney’s 14-foot bronze statue of “Whisper,” the bull that legend says was ridden by Richard Smith to establish his claim to the land that is now Smithtown, was commissioned by a Smith descendent in 1923, although the town didn’t have the will or the money to install it until 1941.

Even privately financed public art, like the imposing monument commemorating the founding of Smithtown, Long Island [right], is often the victim of benign neglect. Charles Rumney’s 14-foot bronze statue of “Whisper,” the bull that legend says was ridden by Richard Smith to establish his claim to the land that is now Smithtown, was commissioned by a Smith descendent in 1923, although the town didn’t have the will or the money to install it until 1941.This is a true Long Island landmark, in my opinion the finest public sculpture in the region, but any casual observer can see that it’s badly in need of restoration. Decades of exposure to the weather, air pollution, and the lack of routine maintenance have left its surface pitted and stained. It probably suffers from bronze disease, which will eventually erode it beyond repair. Annual waxing could have prevented this destructive process, but what did Smithtown know about sculpture preservation?

When you buy a house, you know that sooner or later it’ll need a paint job and a new roof. You know that your car needs an oil change every so many miles, and that if you don’t have your teeth cleaned regularly they’ll fall out. In the public sphere, our parks, beaches and other amenities need constant care to keep them in good condition. So why would you assume that art needs no maintenance?

I’d like to suggest that whenever a public artwork is commissioned, the deal includes an endowment for its upkeep. It wouldn’t take much money to ensure the survival of our monuments–all it takes, in fact, is the realization that they can’t survive on their own.

For “In the Morning,” I’m Helen Harrison.

Art School Confidential

Art Waves commentaries, 2004-2009: A Selection

© 2010 Helen A. Harrison. No reproduction without permission.

Art School Confidential

Broadcast 6/1/06

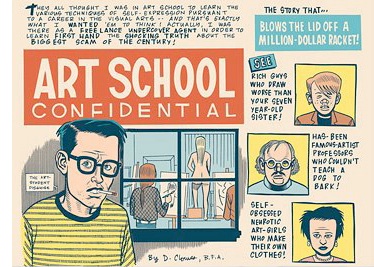

If you’re planning to see this movie, don’t listen to this review. One, because I’m going to give away the ending, and Two, because I may change your mind. On the other hand, you really should see it if you don’t know all the clichés about art-world wannabes, coulda-beens and has-beens. This film is a primer of stereotypes–not one fully developed character makes an appearance in the whole 102 minutes.

If you’re planning to see this movie, don’t listen to this review. One, because I’m going to give away the ending, and Two, because I may change your mind. On the other hand, you really should see it if you don’t know all the clichés about art-world wannabes, coulda-beens and has-beens. This film is a primer of stereotypes–not one fully developed character makes an appearance in the whole 102 minutes.

The story isn’t very long, but it benefits from abbreviation. Jerome goes to an art school called Strathmore Institute and falls in love with the life class model, whose father happens to be a famous artist. She becomes his entrée into the professional art world, which as you might expect is populated by pompous, arrogant, venal manipulators. That also describes Jerome’s fellow students–all except one, who turns out to be an undercover cop.

What the heck is he doing at Strathmore? He’s investigating a series of stranglings on the Strathmore campus, an improbable ivied enclave modeled on Brooklyn’s Pratt Institute but transplanted to SoHo. If this feels phony, that’s because it is–the film was shot in and around Los Angeles, and looks like something cobbled together on the back lot. In class, the students trot out every known theoretical platitude, defensive put-down and jealous innuendo, while their professor–played with his trademark predatory cynicism by John Malkovich–struggles to salvage the wreckage of his own failed artistic ambitions.

The tedium is briefly relieved by Jerome’s visit to an even more pathetic failure, a former Strathmore student who is such a disgustingly abject role model that you wonder why Jerome doesn’t immediately drop out and join the Army. By a marvelous coincidence, this fellow just happens to be the strangler, and of course he paints pictures of his victims. Jerome steals the paintings and passes them off as his own, thereby becoming the chief suspect in the murders. And wouldn’t you know it, his subsequent notoriety makes him a hot property in the art market. Go directly to jail, and you get a waiting list of buyers. Well I’ll be darned–so that’s how you do it.

I think “Art School Confidential” is supposed to be a satire, but the screen writer, Daniel Cowles, is no Voltaire. The humor, what there is of it, is as broad and forced as vaudeville, and just as dated. Max Minghella does a workmanlike job of depicting Jerome as an ambitious but essentially spineless nebbish who never does get the sex he craves. Nor can he paint like the artist whose work he stole. So what will happen to him when he has to produce his own paintings? Well, as Andy Warhol might say, his fifteen minutes will be up.

For “In the Morning,” I’m Helen Harrison.

Theft: A Love Story

Art Waves commentaries, 2004-2009: A Selection

© 2010 Helen A. Harrison. No reproduction without permission.

Theft: A Love Story

Broadcast 8/31/06

In Peter Carey’s new novel, everyone is a crook. The primary narrator, a washed-up Australian painter named Michael Boone, alias Butcher Bones, steals from his patron, who has stolen Michael’s wife. The ex-wife, Michael believes, has stolen his paintings, as well as their son, in the divorce settlement. Michael, in turn, steals someone else’s wife, Marlene Liebowitz, who steals anything that isn’t nailed down–and more. Even the detective who pursues her reveals himself as a petty thief. Dealers steal from artists, collectors steal from dealers, and so it goes, right down to the New York taxi drivers who rob Butcher of his equilibrium–or at least give him someone else to blame for his agitation and clouded judgment.

In Peter Carey’s new novel, everyone is a crook. The primary narrator, a washed-up Australian painter named Michael Boone, alias Butcher Bones, steals from his patron, who has stolen Michael’s wife. The ex-wife, Michael believes, has stolen his paintings, as well as their son, in the divorce settlement. Michael, in turn, steals someone else’s wife, Marlene Liebowitz, who steals anything that isn’t nailed down–and more. Even the detective who pursues her reveals himself as a petty thief. Dealers steal from artists, collectors steal from dealers, and so it goes, right down to the New York taxi drivers who rob Butcher of his equilibrium–or at least give him someone else to blame for his agitation and clouded judgment.Michael’s mentally retarded brother Hugh–or Slow, as his nickname has it–steals more benignly, almost by default. His is the other narrative voice, a dark, distorted echo of his brother’s. He reminds me of John Steinbeck’s Lenny in “Of Mice and Men,” large, strong and volatile, a protector and an avenger. His real crime is to witness the fraud and deception all around him, which makes him potentially even more dangerous. In a sense, you might say that he steals the truth and stores it away in his poor, addled brain. Occasionally it comes spilling out, and that’s always messy.

This larcenous tale is set in the art world of the early 1980s, when Michael’s star is most definitely on the wane. Now in his late 30s, he’s already a has-been in the insular Australian art market, where he was cock of the walk–pun intended–ten years earlier. Oh, the fickle finger of fate. We might muse that this son of a provincial butcher had a phenomenal run of luck, first to escape the family business, which his rough-hewn father was grooming him to inherit–hence his nickname. Then actually to achieve some measure of success as an artist, even if only in his homeland. But no, Michael is mordantly bitter, self-flagellating and comically hapless, a cross between Kurt Vonnegut’s Rabo Karabekian and Joyce Carey’s Gully Jimson–which made me wonder whether Peter Carey is related to the author of “The Horse’s Mouth.”

The plot hinges on the theft of a very valuable painting by Marlene’s long-dead father-in-law–a cubist ranked right up there with Picasso and Braque–and the disappearance of another of his masterpieces. It has a couple of unlikely twists, which I won’t give away, although I will say that the ending is a bit too pat for my taste. The book’s real rewards are in the reading itself, in Carey’s use of language, although it’s very hard to find a suitable passage to quote on the air. The text is heavily larded with vulgarity and profanity, which gives it an earthy tone that suits the characters perfectly. It also cleverly masks the quicksilver turns of phrase and the dead-on aperçus that give Carey’s writing its punch.

Here is Hugh reflecting on his brother’s reaction to Marlene’s promise to get him a solo show in Tokyo:

“It is a big bloody mystery to me that a man so set against Queen Elizabeth of England could get himself so rigid about the crown princess of Japan, but soon he has a great stiffy, throbbing like a sock full of grasshoppers. And who am I to understand his secret squirming brain?”

No mystery at all, Slow Bones. You got the simile just right, and you nailed your brother’s hypocracy in that about-face on royalty. Principles be damned. This is his chance for a comeback. And he’s about to grab it by the you-know-whats.

In fact, this is not so much his comeback as his payback for the enormous favor he’s about to do Marlene, who has a vested interest in, shall we say, his success. In the end, the artist is nothing more than a hired gun, producing to order what he thinks, or knows, will please his client. That he happens to be in love with his client is a minor complication. In their odyssey from Sydney to SoHo, Michael discovers the true extent of Marlene’s thievery, but along the way he accumulates a raft of insights–none of which are of any use to him, of course.

Time, the greatest thief of all, teaches him nothing.

For “In the Morning,” I’m Helen Harrison.

Art Czar

Art Waves commentaries, 2004-2009: A Selection

© 2010 Helen A. Harrison. No reproduction without permission.

Art Czar

Broadcast 1/18/07

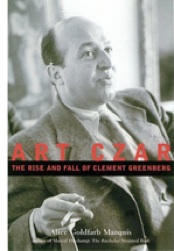

For this latest look at the life and career of the man widely regarded as the most influential American art critic of the 20th century, the author, Alice Goldfarb Marquis, had access to Greenberg’s papers, which were bought by the Getty a few years ago. Apparently he never threw away a single scrap of paper, and Marquis struck more than one rich vein in that particular gold mine. Two especially valuable sources are the drafts and revisions of his articles, reviews and lectures, including lots of unpublished material, and his journals, which give a day-by-day account of his social and professional life, and often of his moods as well.

Another treasure trove is his correspondence with a college friend, Harold Lazarus, which were published in 2000 as “The Harold Letters.” If ever there was a case to be made for burning one’s youthful ramblings, these letters make it–and Marquis, a visiting scholar at U. Cal. San Diego, uses them extensively to prove what a creep Greenberg was, pretty much from the get-go.

Another treasure trove is his correspondence with a college friend, Harold Lazarus, which were published in 2000 as “The Harold Letters.” If ever there was a case to be made for burning one’s youthful ramblings, these letters make it–and Marquis, a visiting scholar at U. Cal. San Diego, uses them extensively to prove what a creep Greenberg was, pretty much from the get-go.

This is not a long book, and I felt that there was more to the story than I was given–hell, I know there was. Both Marquis, and Greenberg’s previous biographer, Florence Rubenfeld, came to the Pollock-Krasner House to do research, since we have relevant material in the archives. He was, after all, one of Jackson Pollock’s most ardent champions, and was a frequent visitor to the house while the artist was alive. He came back for a talk to our Stony Brook graduate students in 1991, three years before his death, and that was the only time I met him. By then he was physically frail, racked by emphysema, but mentally alert, sober and still feisty–although he was better behaved than I’d expected, given his reputation as a combative and even insulting speaker, as well as a mean drunk.

Marquis wades deep into these murky waters, ascribing much of Greenberg’s arrogance and bluster to–here we go again–Jewish self-hatred. Yes, the Harold letters contain ample evidence of his disdain for his co-religionists, yet he worked as an editor of a Jewish magazine, and maintained that every word he ever wrote was a reflection of his Jewishness. He also expressed plenty of disdain for Gentiles, homosexuals, artists and women–no indication of his feelings for small furry animals, but since they have heartbeats he probably wasn’t too fond of them, either. So maybe the guy was just a neurotic screw-up with a non-denominational chip on his shoulder.

Certain aspects of Greenberg’s public life have already been thoroughly rehearsed, including his adversarial relationship with his fellow critic Harold Rosenberg, his involvement in the art market, which some people accused him of manipulating to benefit the artists he favored, and his high-handed attitude toward the sculpture in the estate of David Smith, of which he was an executor. But other, more intimate, things, like the unbalanced state of mind often revealed in his journal entries, and the insecurity illustrated by the obsessive self-criticism of his own writings and statements, haven’t been so thoroughly examined before, and they really make you wonder how the guy got to be so powerful.

On that point I have to quibble with the book’s title, “Art Czar.” Yes, it’s catchy, but it implies that Greenberg occupied an imperial position in the art world, with an army of defenders at his command. On the contrary, he was a lonely voice crying out in a philistine wilderness, even during his heyday in the 1940s and 50s, and even moreso after the advent of Pop art opened the floodgates to the sort of lowbrow kitsch he despised.

As long as I’m quibbling, there are also some careless mistakes in the book, like the wrong name for an important organization founded in 1936, the American Abstract Artists, which Marquis says continued until the 1960s but in fact still exists, and for Solomon Guggenheim’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting. She also gives the wrong date for the opening of his niece Peggy’s avant-garde gallery, Art of This Century.

She writes that there was only a single museum of modern art in the United States in the 1940s, inexplicably forgetting about the Phillips Collection in Washington, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, not to mention the Museum of Non-Objective Painting. She dismisses Pollock’s parents as “what we would now call trailer trash,” but they were nothing of the sort–they were hard-working property owners. And she maintains that Pollock wasn’t able to cash in on the publicity from a profile in Life magazine, but a few pages later she notes, quite correctly, that he sold a record number of works from the show he had three months after the article appeared. Sounds to me suspiciously like cashing in.

To be sure, these are minor shortcomings in a biography that’s otherwise well written and carefully researched, although the end notes aren’t as comprehensive as I would wish. Maybe the problem is more with the subject than with the author. Marquis’s Greenberg left me feeling ambivalent–wanting to know more about the world he lived in, but feeling I now know more than I want to about the kind of man I wouldn’t care to know at all.

For “In the Morning,” I’m Helen Harrison.